RUMORS OF ROYALTY

The Road to Revolution

The events of 1688-89 in England were neither “glorious” nor a revolution by the analysis of many modern historians. And yet the phrase “Glorious Revolution” has wedged its way into collective western historical consciousness for the events surrounding the deposing of King James II and the rise of the House of Orange into power.

“The Glorious Revolution” conjures vague images of Dutch princes, a regime change, and co-rulers—but what exactly happened at the end of the 17th century to bring about this revolution that was more of an invasion?

To understand that, we return to the early 17th century and the English Civil War.

Long Live King Charles I

Charles inherited the throne from his father King James I in 1625, and almost immediately became embroiled in a series of military skirmishes on the European continent and in the Americas. Some of his involvement was understandable—his sister Elizabeth had been deposed as Queen of Bohemia by the Holy Roman Emperor, and Charles tried to help her. But these military ventures were unpopular with much of Parliament and the populace. Charles also gained a well-earned reputation for an unwillingness to cooperate with Parliament; he preferred a more autocratic style of rule than Parliament was prepared to accept.

In 1637, Charles tried to impose the English Book of Common Prayer on Scotland. Naturally, this did not sit well with the very Presbyterian and very independent Scots, who resented the forced introduction of an Anglican religious form. The Scottish Parliament and the Kirk (the Presbyterian Church of Scotland) rejected Charles’s high-handed move and made the full weight of their displeasure known. Charles spent about three years trying to put down riots and revolts in Scotland, and just when he thought that country had been subdued, the political situation in Ireland deteriorated.

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, was the Lord Deputy of Ireland and Charles’s right hand man. Strafford had used violence and coercion to bring Ireland into line with what Charles wanted from them (taxes, mostly), and managed to achieve the seemingly impossible: unite the disparate factions in Ireland against him. As the Catholic-dominated Ireland made a bid to regain their autonomy, rumors began swirling in England that the Catholic-sympathizing Charles was involved in that rebellion. The rumors escalated with the notion that the English Parliament was going to impeach Henrietta Maria—Charles’ Catholic queen—for supposedly conspiring with Irish rebels against the Crown.

Charles intended to personally arrest five members of the House of Commons who were supposedly going to start the impeachment hearings again Henrietta Maria, but they were alerted and fled ahead of the king’s arrival. This proved to be the last straw for those already frustrated with the king. England was divided into those who supported Parliament (Parliamentarians), and those who supported the Crown (Royalists). By mid 1642 both Parliamentarians and Royalists were arming themselves in anticipation of military conflict.

Many of the Royalist supporters fled to the continent, particularly to the Dutch Republic and Germany. Which turned out to be a good thing, because Charles’s military campaigns on home soil didn’t meet any more success than his earlier ones in foreign lands. By 1649, Charles was captured, tried, and executed.

Below, an engraving imagines Charles on the eve of his execution, from a 1665 volume of Royalist poetry honoring the king.

From the Commonwealth to King Charles II

Meanwhile, Oliver Cromwell, leader of the Parliamentarians, had stepped to the fore. He subdued Ireland by 1650 and was named the “Lord Protector” in 1653. Guided by the Lord Protector, the Parliamentarians governed England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland as a republic known as the Commonwealth. Unfortunately for the supporters of the Commonwealth, Cromwell died in 1658 and his son proved to be a poor successor.

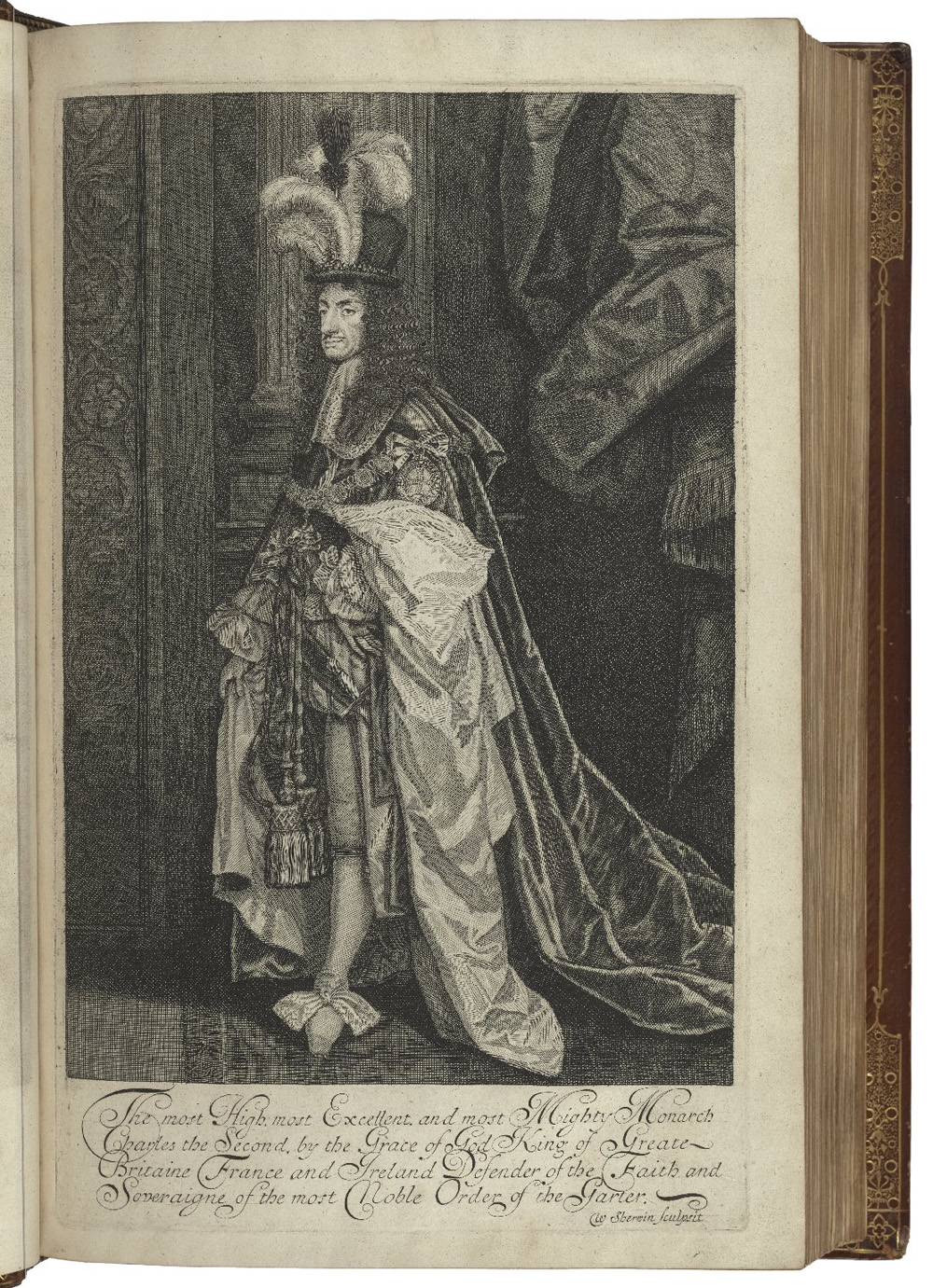

A lavishly dressed Charles II. Folger A3983.

The situation deteriorated to the point that, in early 1660, Parliament invited the son of King Charles I, also named Charles, to retake the throne as King Charles II.

The younger Charles spent much of the early 1640s with his father, aiding the royal cause, but by 1646 the prince had been removed to the safety of the French court where his mother was residing, and then in 1648 to the Hague with his sister Mary and her husband William II, Prince of Orange. (This isn’t the William and Mary who would take over the English throne in 1689. This is the previous generation. Royal families tend to reuse names frequently.)

King Charles II’s restoration to the English throne saw not only a political shift, from commonwealth back to monarchy, but a social and religious shift too, as Charles took steps toward religious toleration. The now-victorious Royalists were overwhelmingly Anglican (that is, Church of England), and there was a general rejection of the Puritan-based ideals that had dominated Cromwell’s Commonwealth. Like his father before him, Charles married a Catholic princess: Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza.

Catherine of Braganza, Charles II’s long-suffering wife. Folger Art Box G249 no. 1.

This marriage brought with it the strategic ports of Tangier, Morocco and Bombay, India, trading rights in both the Atlantic and Pacific, and freedom of worship for Catherine, including a secret Catholic wedding ceremony in addition to the public Anglican ceremony.

Charles’s religious toleration would come back to haunt him. By the mid 1670s, fears abounded that Catherine was actively converting Charles and his brother James to Catholicism. (These fears partly hit their mark–Charles and James did convert, though independent of Catherine’s influence.) And Catherine failed to bear a legitimate heir to the throne; while Charles fathered many children with his mistresses, Catherine failed to carry any child to term. These miscarriages had some factions of the English government calling for a royal divorce. Charles refused, however, and despite their somewhat rocky relationship, Catherine was with Charles in his final illness in 1685.

Charles II’s lack of a legitimate heir meant that the throne fell to his younger brother James, who became King James II of England (and VII of Scotland).

The Turbulent Reign of King James II

John Riley, James, Duke of York, Later King James II, The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Like his older brother, King James II had spent much of the 1650s in exile on the continent. After Charles II became king, James became the Lord High Admiral, and acquitted himself well during the Anglo-Dutch wars of the middle 17th century. However, James left his position after the first Test Act of 1673. The law was designed to disallow those not following the Anglican faith (Catholics in particular) from holding office. James chose to resign rather than take the required oath. By 1676, he had joined his second wife, Mary of Modena, in openly worshiping as a Catholic.

1678 brought the Popish Plot, in which a group of Catholics allegedly conspired to have King Charles II assassinated so that he could be succeeded by the Catholic James. In the fallout, James found himself exiled from England, first in Brussels and then in Scotland, until 1685 when Charles passed away and James became king.

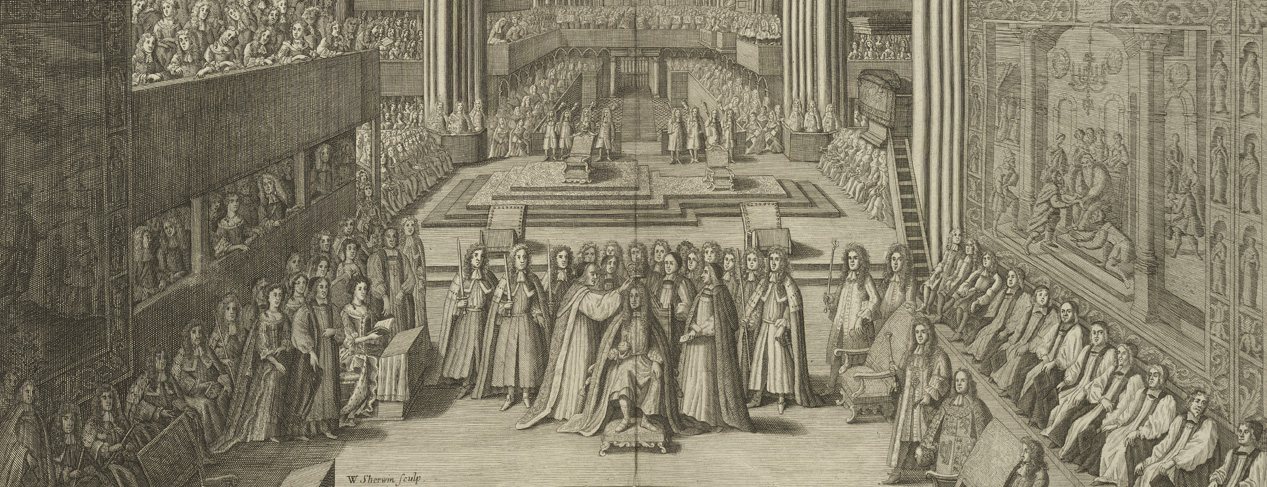

Below, the coronation of James II from a volume commemorating the event.

Although there was considerable anxiety amongst those in the English government and church upon Charles’s death, James’s transition to the throne went smoothly. James helped his own cause by promising to maintain the Church of England rather than abolish it, as some feared. He also sought to elevate his fellow Catholics, repealing many of the restrictions that had been in place for the last century.

However, like his brother and father before him, James struggled to find balance with the representative governments in the three countries he ruled. His preference for his fellow Catholics brought him in conflict with those already in power, even in Catholic Ireland. James had ruled as absolute monarch over the colonies in the Americas that he controlled, and many feared he would try to impose the same absolute rule over England, Scotland, and Ireland.

By the second year of his reign, it seemed that those fears were well-founded. By 1687, James was promoting a policy of toleration for anyone who did not conform to the Anglican faith. While that kind of religious toleration was a good thing, James’s method left much to be desired. Instead of working together with Parliament and the Church of England to promote his views, James operated by fiat, granting indulgences and suspending penal laws (which imposed restrictions on non-Anglicans) as he saw fit. When members of Parliament wouldn’t support his decrees, he dissolved Parliament in July 1687 and went on an active campaign to encourage the populace to elect people whose beliefs matched those of their king.

James set up commissions to ensure that the representatives elected to the House of Commons would align with his own views. He also sent messengers around the country to gauge popular sentiment for religious toleration.

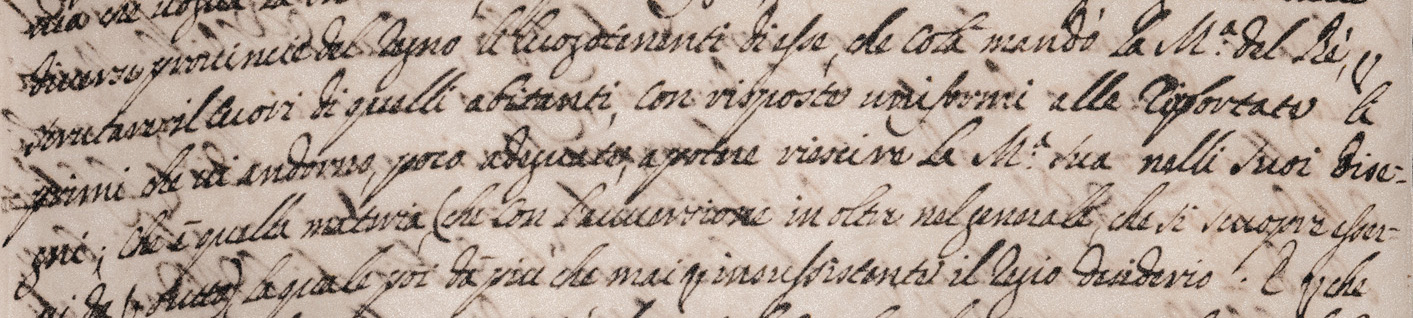

Terriesi writes of the turn against James

The increasing hostility of King James II’s subjects was obvious to Terriesi, whose dispatch to Florence on January 12, 1688 noted the breach between the king’s intentions and his people’s desires upon the messengers’ return.

Li luogotenenti di esse che colà mandò la maestà del re, scrutare li cuori di quelli abitanti con risposte uniformi alle riportate li primi che vi andorno poco adeguati a potere riuscire la maestà sua nelli suoi disegni, che e quelli maturi (che con l’avversione in oltre nel generale che si scuopre esservi da per tutto) la quale poi da più che mai per insuficiente il regio desiderio. [Regularized Italian transcription]

The provincial lieutenants, whom his majesty sent out to scrutinize the hearts of the English people, returned with the same results as the first who had undertaken that mission, results which are inadequate to his majesty’s designs. This reception (in addition to the general aversion that seems to be everywhere) renders the royal desire more groundless than ever. [Modern English translation]

Francesco Terriesi to Francesco Panciatichi, January 12, 1688. Medici Archive Project DOC ID 30079.However, these attempts backfired and by the end of 1687, the majority of the population had turned against James. It was clear that tolerance for Catholics and non-Anglican Protestants wasn’t wanted. Around this time, it became known that James’s wife Mary was with child. For James’ subjects, this suddenly raised the specter of a legitimate, Catholic successor to the English crown. James’s two surviving daughters from his first marriage were both known to be Anglican (and one was married to the Dutch ruler), but if the new child was male, he would supersede his half-sisters and jump to the top of the line of succession.

The situation was primed for a disaster: an autocratic monarch, a disaffected populace, religious conflict, and potential intervention from a foreign power. The year 1688 dawned with the potential for trouble. And yet, amazingly, the disaster did not occur. The crown of England would change hands without a multi-year war, and a new order of succession would be established without the death of the previous king.

PREVIOUS: An introduction to the people involved in these maneuvers for the English throne.

NEXT: Read on to learn how a timely pregnancy, an unlucky woman, some well-timed rumors, and a tiny infant brought about a “Glorious Revolution.”