RUMORS OF ROYALTY

A Crisis of Succession

A series of events began in December 1687 that would eventually end in the removal of King James II from the throne and the exile of his queen, Mary of Modena, to France for the remainder of her life. In that month, it was announced that Queen Mary was pregnant.

So how did the birth of an heir to the throne—an event which is usually cause for celebration—bring about the removal of the very family line he was meant to secure?

Setting the Stage

By the end of 1687, the political situation in England was close to disaster. King James II’s two years on the throne had realized the fears of his detractors: that he was a Catholic-promoting autocrat with little use for collective rule. James was trying to overturn legislation that penalized Catholics (and other nonconformists) and was actively trying to stack the House of Commons with those sympathetic to his wants. The populace was turning against him, and the Protestant nobility were just about at their wits’ end.

A Dutch engraving of Mary of Modena and her son, with whom she was pregnant in late 1687. “The young princes of Walles.” Folger ART 230- 988.

All of this had England bracing for a crisis, and they got one, which played out in slow motion over the next twelve months. The announcement of Queen Mary’s pregnancy was the first step. Suddenly faced with the looming prospect of a legitimate, Catholic heir to the English throne (for there could be no doubt that the child would be raised in the Catholic Church), the Protestant population of England came close to panic.

Something had to be done to prevent the child, if it was male, from superseding King James II’s (Anglican) daughters Mary and Anne in the line of succession.

Almost immediately, doubt was cast on Queen Mary’s pregnancy. Mary was known to want only Catholic women attend her in previous pregnancies. This allowed the Protestant detractors to undermine claims of the “proof”, noting that the physical signs of pregnancy could be fabricated. As the months of 1688 progressed, it became harder to deny the evidence of Mary’s pregnancy, and reports about the upcoming birth spread across the continent.

Terriesi writes as Queen Mary’s pregnancy progresses

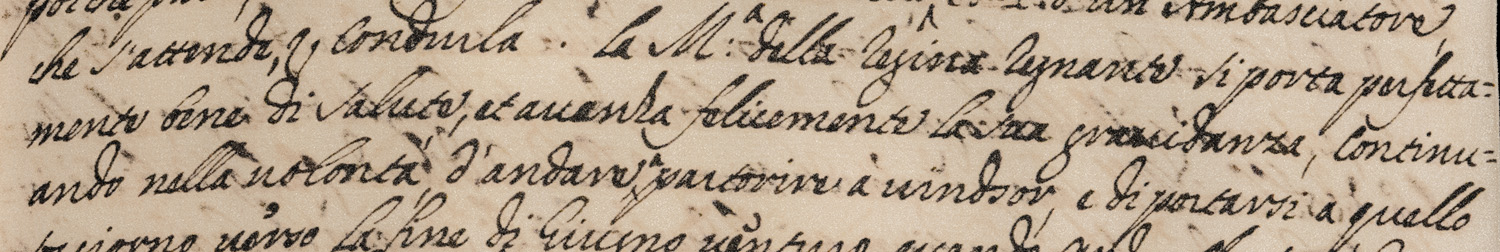

Like much of London, Terriesi kept abreast of news of Queen Mary’s pregnancy. Several of his avvisi from winter and spring 1688 include little updates like the following:

La maestà della regina regnante [Mary of Modena] si porta perfettamente bene di salute, et avanza felicemente la sua gravidanza, continuando nella volontà d’andare a partorire a Uindsor. [Regularized Italian transcription]

Her majesty the reigning queen [Mary of Modena] is in perfect health, her pregnancy progresses happily, and she continues in her decision to go to Windsor to give birth. [Modern English translation]

Francesco Terriesi to Francesco Panciatichi, March 1, 1688. Medici Archive Project DOC ID 30086.

Rumors persisted: both that Queen Mary was faking the pregnancy and that while she might actually be pregnant, the father was not King James II. The burden of proof for legitimizing the pregnancy fell entirely on Mary, who would never be able to meet her critics’ claims.

The critics included Princess Anne, who had no particular love for her step-mother, and was skeptical about the claims of pregnancy. She wrote to her sister Mary expressing disbelief, first about the legitimacy of the pregnancy itself, and then about whether any child presented was actually of the queen’s body: “I declare I shall not [believe the child to be the queen’s], except I see the child and she parted” (that is, be present for the actual birth). Unfortunately for King James II and Queen Mary, Anne was in Bath (dealing with the after-effects of her own miscarriage) on June 10, 1688, depriving the couple of a highly credible witness to the royal birth.

The Royal Child

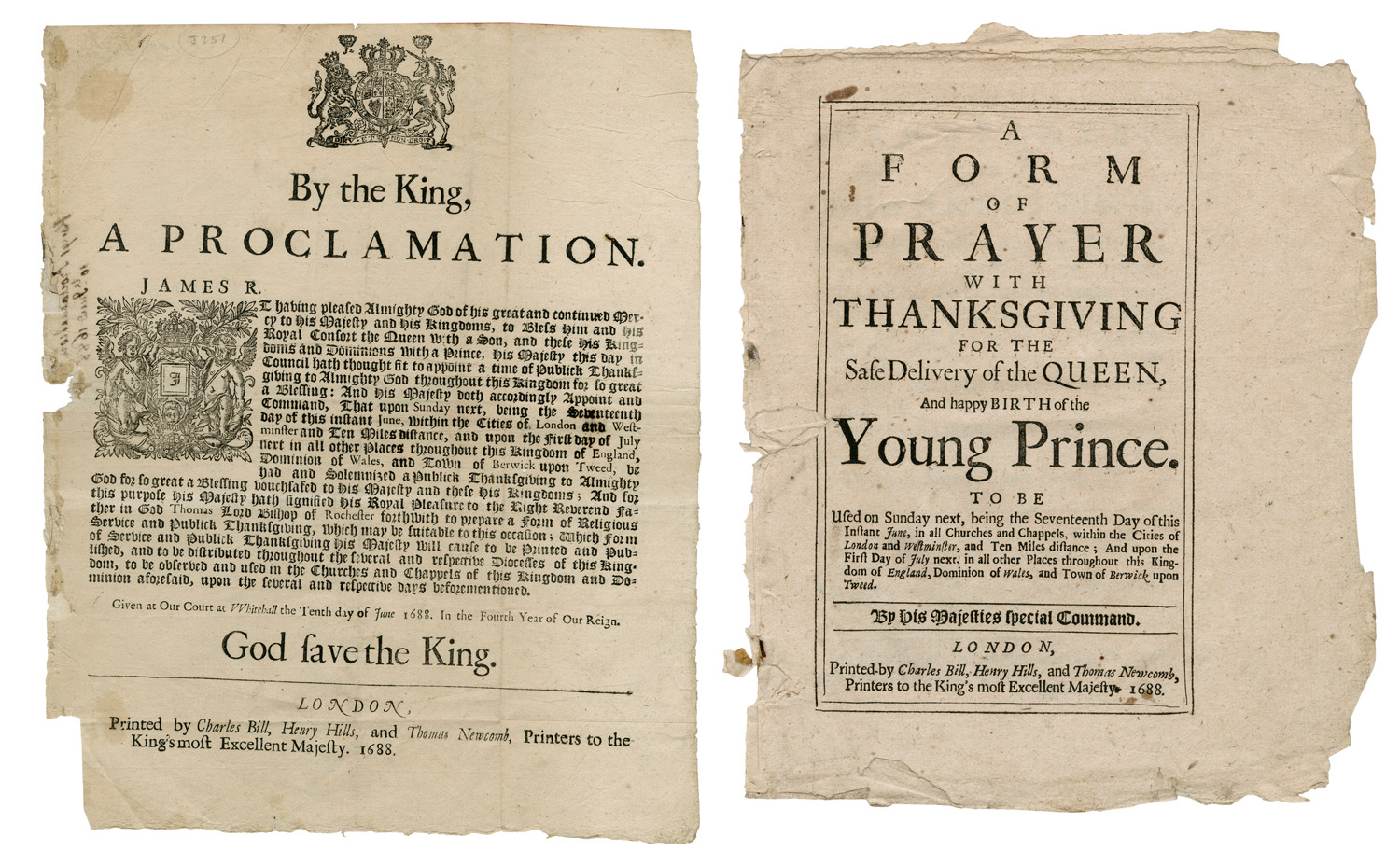

Upon the birth of his son, James Francis Edward, King James II declared a day of thanksgiving, to be celebrated on the following Sunday, June 17th, “within the cities of London and Westminster” and within ten miles thereof, and on “the first day of July” everywhere else (to allow news to spread, supposedly).

The June 10 proclamation (above left) prompted the Bishop of Rochester to write a service that was supposed to be performed on those days. It was printed shortly after the proclamation, so that it could be distributed to all of the parishes. A testimony from such a well-placed individual served as legitimizing evidence for the birth.

However, the printed news wasn’t all good for the royal family. Once again, there were doubts about the birth—both whether the queen had given birth at all and whether the child was truly James’s son. As Anne predicted, those who were not physically present at the birth were skeptical of the claims of legitimacy. The preferred tale was that the queen gave birth to a stillborn child—something which had happened to her several times previously—and that a live child was smuggled in on a warming pan (or bed warmer) and presented as the queen’s own.

King James II does not seem to have had an instinctive grasp on how to handle public opinion. He chose to respond with formality. On October 22, 1688, he summoned everyone who was witness to the royal birth and had them testify before the Privy Council and other peers regarding the validity of the birth and the legitimacy of his heir.

Terriesi writes of James’ efforts to legitimize his heir

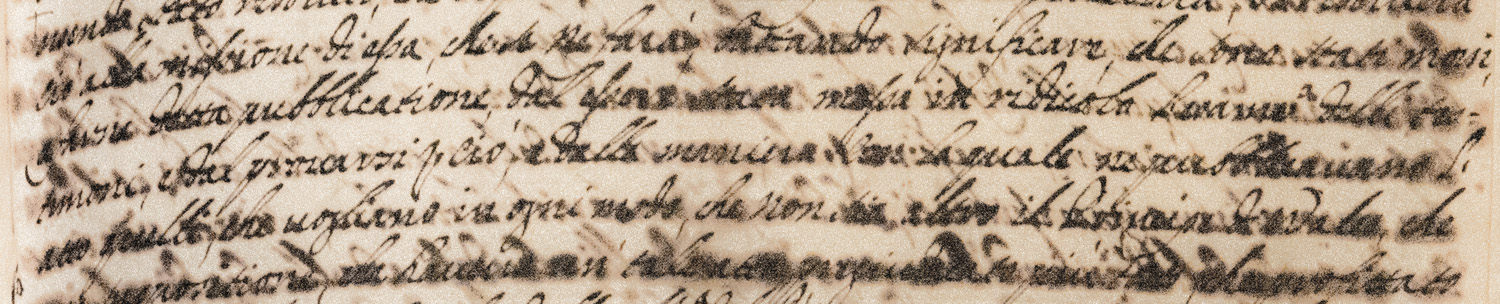

By October 29, when Terriesi reported on the witnesses’ depositions, the Crown had published the testimony; Terriesi included a copy with his avviso.

… bastando significare che sono stati mossi a fare tale pubblicatione dal essere stata messa in ridicolo l’esamini delli testimoni, e dal provarsi per ciò e dalla maniera con la quale ne pubblicavano l’atto quelli che vogliano in ogni modo che non sia altro il principe di Wales che una suppositione… [Regularized Italian transcription]

… suffice it to say that they were motivated to make such a publication from the way the witness examinations were made to look ridiculous, by the trials themselves, and by the way in which the record has been publicized by those who wish in every way that the next Prince of Wales is merely supposition… [Modern English translation]

Francesco Terriesi to Francesco Panciatichi, October 29, 1688. Medici Archive Project DOC ID 30120.

James’ choice proved unfortunate in the end, as the formality did little to change public opinion. The credibility of the witnesses was easily undermined (many were women, many were Catholic, others couldn’t see clearly in the crowded room, the queen was removed to another room immediately after giving birth, etc.).

A Protestant Alternative

In direct contrast to King James II’s poor use of the press, William of Orange launched a much more successful print propaganda campaign. William had been keeping an eye on the situation in England—this made sense, given that his wife Mary had the strongest claim to the English throne until her half-brother James Francis Edward was born. He begun a subtle but effective campaign to position himself as a viable alternative to James.

Pamphlets and printed letters appeared in London as early as 1687, testifying to William’s critical opinions of James’s policies. In his March 8, 1688 avviso, Terriesi describes the inadequacy of James’s efforts to stem the tide of pamphlets and satires mocking the king and queen, including those that originated in the Netherlands with the approval of William of Orange.

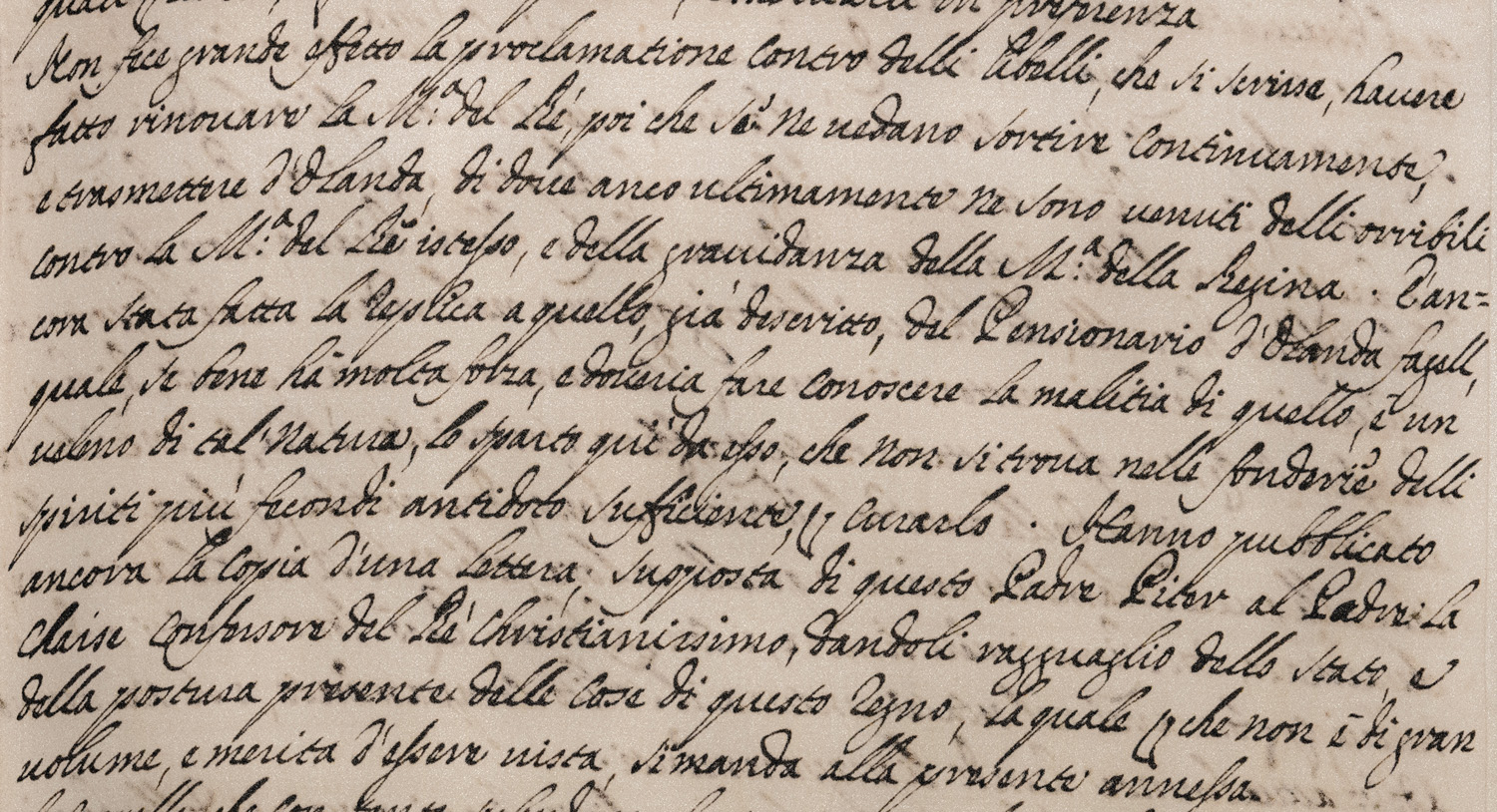

Terriesi writes of James II’s ineffective ban on libels

According to Terriesi, King James II’s ban on libels had no effect on an inflammatory fake letter supposedly written by Edward Petre (a Jesuit and a member of James’s Privy Council) to François d’Aix de la Chaise, confessor to Louis XIV.

Non fece grande effetto la proclamatione contro delli libelli che si scrisse havere fatto rinovare la maestà del re [James II Stuart]… Hanno pubblicato ancora la copia d’una lettera supposta di questo padre Piter [Edward Petre] al padre la Chaise [François d’Aix de la Chaise] confessore del re christianissimo, dandoli ragguaglio dello stato e della postura presente delle cose di questo regno, la quale perché non è di gran volume e merita d’essere vista, si manda alla presente annessa. [Regularized Italian transcription].

The proclamation against libelous publications that was renewed by his majesty the king had little effect. They [the king’s opponents] have also published the copy of a letter supposedly written by this Father Piter [Edward Petre] to Father la Chaise [François d’Aix de la Chaise], father confessor of his most Christian majesty [King Louis XIV of France], in which he reports on the situation and current state of the matters of this reign, and which, since it is not of great length and deserves to be seen, is enclosed with the present letter. [Modern English translation]

Francesco Terriesi to Francesco Panciatichi, March 8, 1688. Medici Archive Project DOC ID 30087.

A few weeks after the birth of the new prince, a group of English nobles issued an invitation to William, asking him to intervene in English affairs and prevent the establishment of a Catholic dynasty.

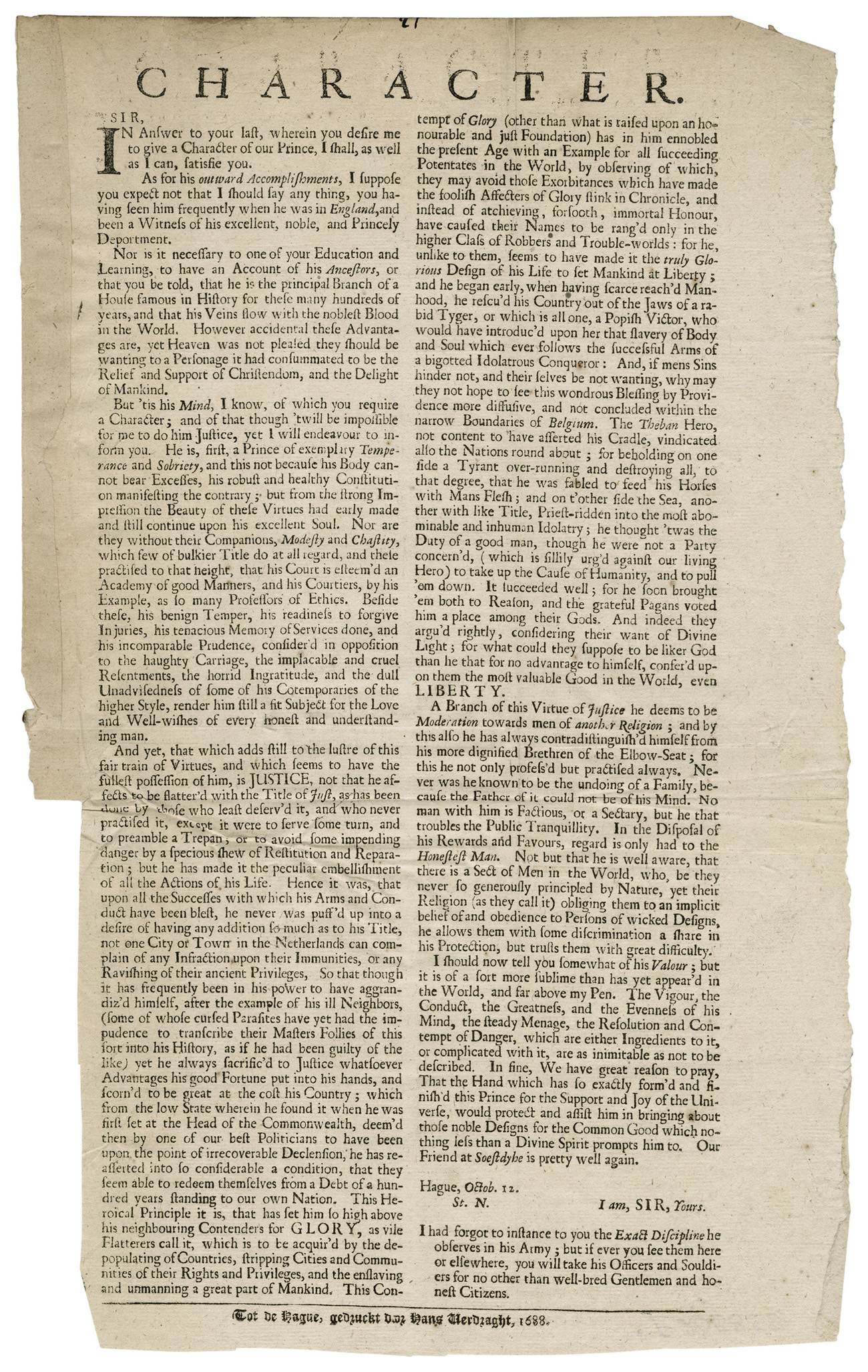

While King James II was ineffectually trying to argue for the legitimacy of his son, William had a flattering tract published at The Hague. This broadsheet, published in English and clearly intended for a London audience, was a glowing character reference for a man about to invade England.

Similar publications appeared, timed with William’s arrival on the southern English coast on November 5, 1688 (accompanied by an “escort” of nearly 15,000 fighters) and the Parliamentary Convention that was called to decide what ought to be done about the English throne. These publications were meant to appeal to a wide variety of readers and shore up the public image of William.It worked. Faced with rumor and innuendo that seemed impossible to curtail, an invading force at his doorstep, and a completely unsympathetic populace and nobility, King James II fled England in December 1688 rather than be forcibly deposed.

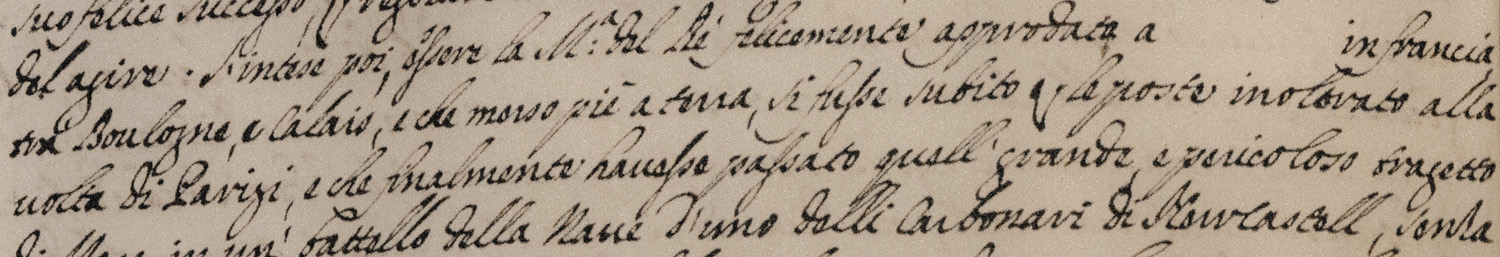

Terriesi writes as James flees

In this newsletter, Terriesi leaves blank the exact site of King James II’s landing in France, either to keep the location secret or because he did not know it.

S’intese poi essere la maestà del re felicemente approdata a [blank] in Francia tra Boulogne e Calais, e che messo piè a terra, si fusse subito per le poste inoltrato alla volta di Parigi, e che finalmente havesse passato quell grande e pericoloso tragetto di mare in un battello della nave d’uno delli carbonari di Newcastell [Newcastle].[Regularized Italian transcription]

It was then heard that his majesty the king happily landed at [blank] in France between Boulogne and Calais, and as soon as his feet touched the ground, he immediately went post-haste in the direction of Paris, and that he had finally passed that great and dangerous sea journey in a ship of one of the coal merchants of Newcastell [Newcastle]. [Modern English translation]

Francesco Terriesi to Francesco Panciatichi, December 31, 1688. Medici Archive Project DOC ID 30116.

King William III and Queen Mary II were crowned as co-monarchs (in an effort to keep up at least the appearance of a hereditary succession) in February 1689.

Below, a print depicting William III and Mary II, captioned with laudatory verse by Dutch poet Ludolph Smids.

The Warming-Pan Scandal Persists

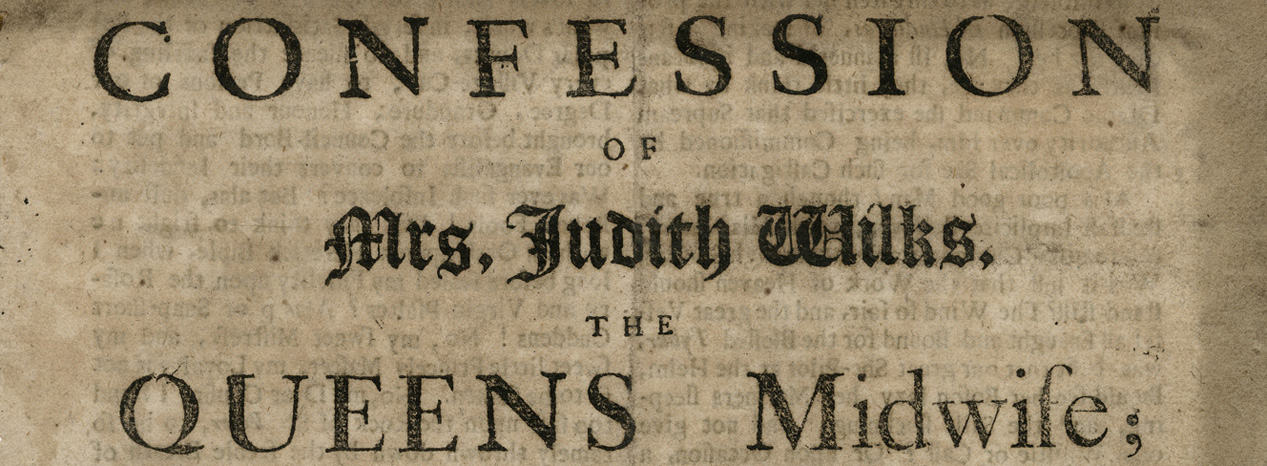

However, despite King James II’s stepping down from the throne in favor of his daughter and son-in-law, the rumors about James Francis Edward’s legitimacy persisted, and even grew. In true tabloid style, interviews with the supposed midwife and the supposed mother appeared in the years following.

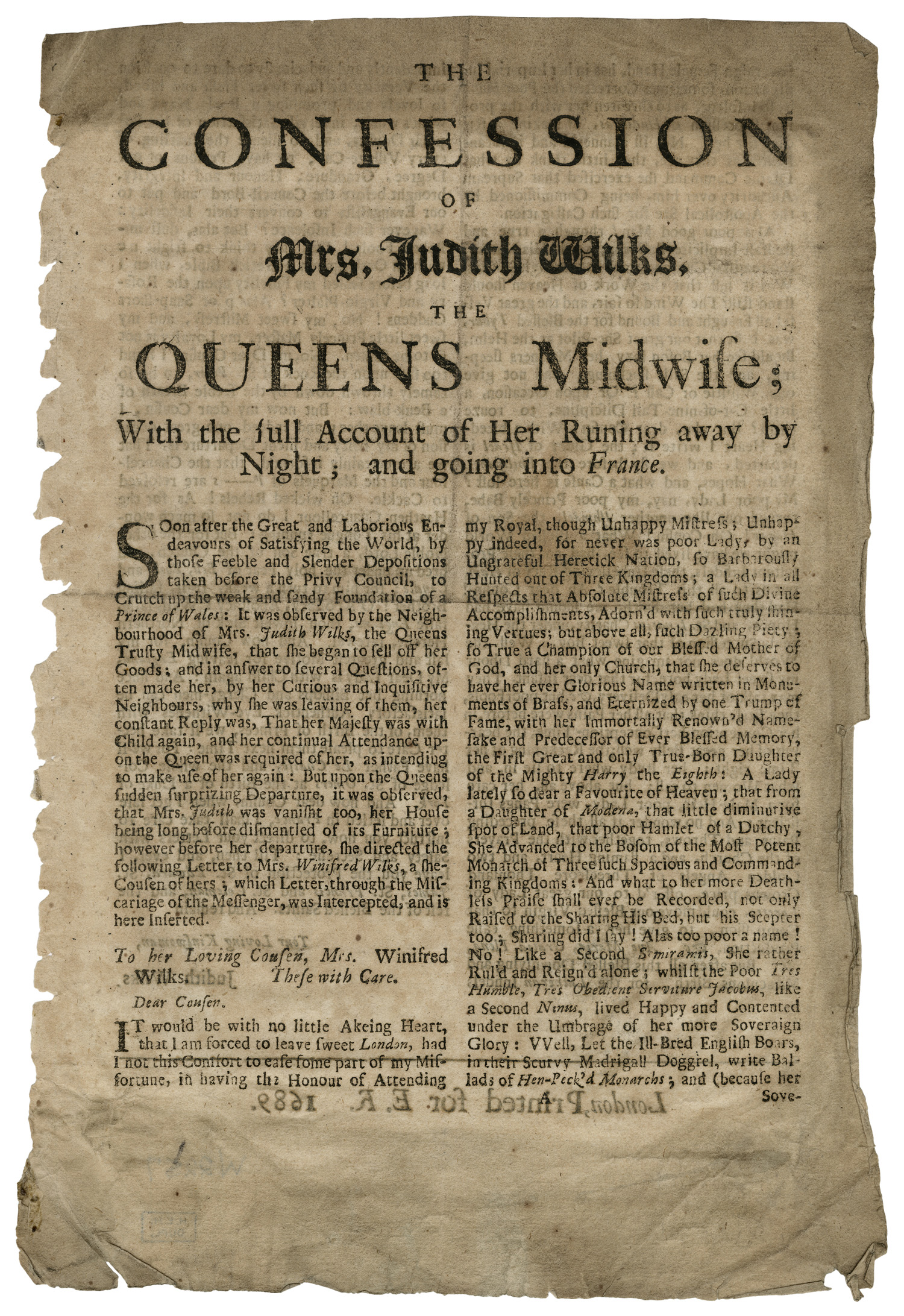

In an anti-Stuart broadside printed in 1689, the story goes that after Queen Mary fled to France at the end of 1688, the queen’s midwife, one Judith Wilks, was discovered to have vanished from her London home. This letter, at right, from Wilks to her cousin–likely fabricated–attempts to explain the reason for her sudden disappearance.

The stated reason is that Queen Mary was with child again, and thus would have need of her midwife in France. This opening gambit was meant to establish the narrator as unreliable with the English audience: it was well known that Mary had trouble carrying a child to term, and that the children she did give birth to were sickly and rarely survived infancy. The writer then goes on to heap lavish praise on Mary, comparing her to both the Virgin Mary and to Queen Elizabeth. This comparison to two well-known virgins was no accident. It yet again played up the fact that James Francis Edward might not be King James II’s son; after all, if the biblical Mary needed no direct male help to get pregnant, why couldn’t it be done again? Doubts were cast on Mary’s position as both queen and mother.

Such tactics were common in the literature that worked to delegitimize the child immediately following his birth. It rarely stated outright that he wasn’t King James II’s son, but hinted around the idea in a suggestive manner.

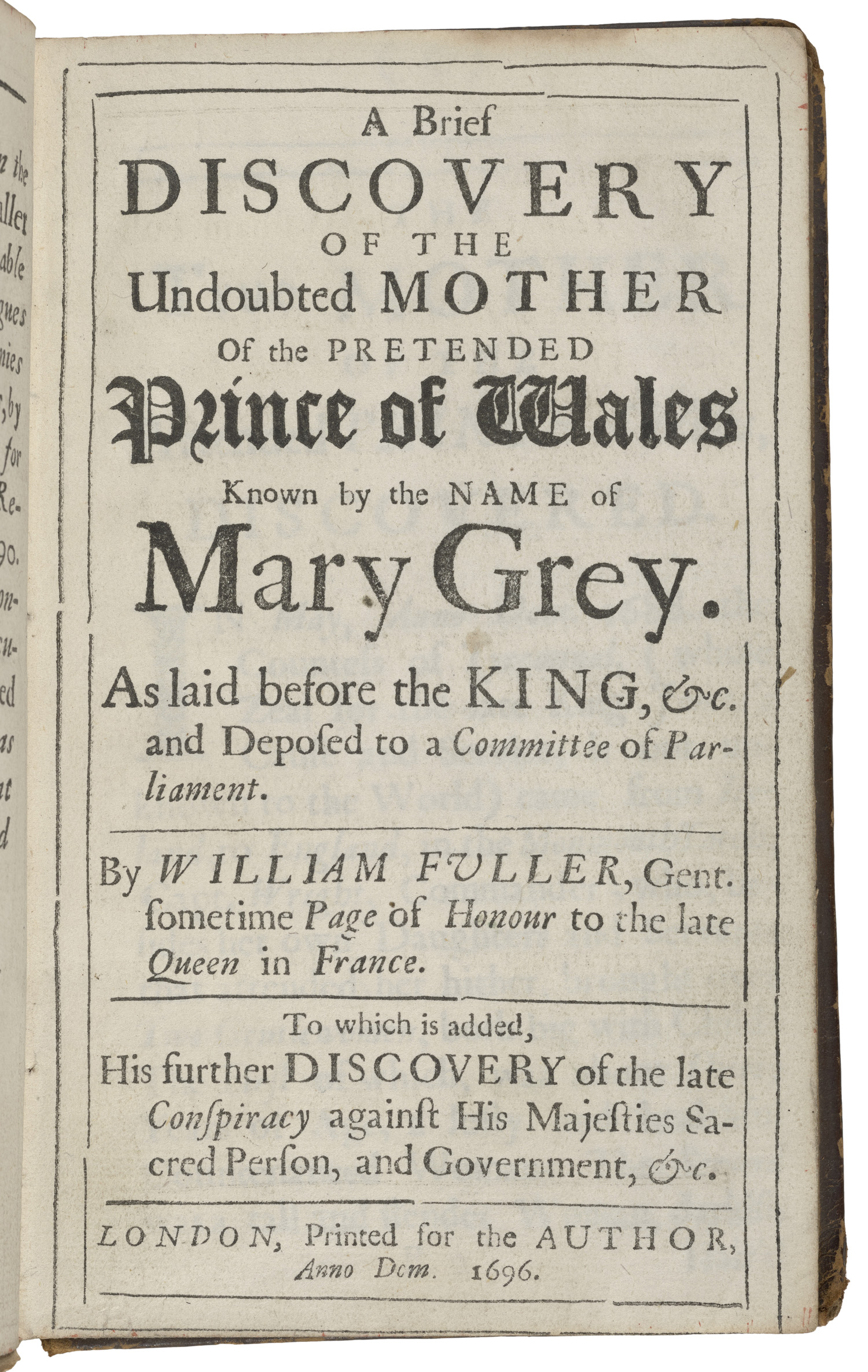

The conspiracy continues: pamphlets like this one, printed in 1696, when James II’s heir was eight years old, perpetually “discover” new information about his birth. Folger 145- 361.1q.

However, as time went on, and James’s family was safely tucked away in the French court, the literature grew more bold in the claims. A set of pamphlets nearly eight years later claimed to have identified (and interviewed) the true mother of the child.

There, then, was the pinnacle of the warming-pan scandal: not just innuendo that the person posing as the Prince of Wales was not born of the body of the former queen, but “proof” in the form of words of the woman who did give birth.

The issue of James Francis Edward’s legitimacy was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, King William III and his Protestant supporters in England had to undermine the validity of the birth to ensure their own political success; however, once they had done so, they found that they had begun to undermine the whole idea of hereditary rule. After all, the same arguments used in the warming-pan scandal (how do we know the child was really born of this woman? How do we know who the father was?) could be applied to any royal birth.

William made his claim to the throne based on hereditary rule, through his wife Queen Mary II, but he found he had to back off the issue in order to secure his hold on the throne, and had to put up with the possibility of a Jacobite rival.

The nickname “The Old Pretender” was soon applied to James Frances Edward, and stuck to him for the rest of his life. Despite the backing of the French court, the Jacobite heirs never regained the English throne. Attempts to restore the throne to the Stuart line were made in 1715 (after the death of Queen Anne, who died without any direct heirs; the throne went to a collateral line and began the Hanoverian reign). It happened again in 1719. James Francis Edward’s son Charles Edward, Bonnie Prince Charlie, who was sometimes known as the Young Pretender, made another failed attempt to regain the throne in 1745.

PREVIOUS: Revisit the half-century of history that preceded King William III and Queen Mary II’s ascent to the English throne.

NEXT: Go forward to learn more about this project.