RUMORS OF ROYALTY

Pamphlets, Letters, and Propaganda from the Glorious Revolution

Who makes the news? Late 17th-century Europe was as obsessed with the spread of information as many of us are in the 21st century. For kings, queens, and aristocrats, effective courting of public opinion could mean keeping a throne. Failing to win the support of the public could mean losing a throne. For statesmen, diplomats, and others who mingled and moved at the royal level, access to information was a gateway to influence and a barometer of status.

In 1688, the Catholic King James II of England was replaced by the Protestant King William III and Queen Mary II without a full-scale war, in a series of events known today as the Glorious Revolution. Rumors of Royalty brings together English printed material and the private newsletters, or avvisi, of a Florentine diplomat to tell that story through the words of those who were documenting a revolution.

The Florentine Correspondent

The scion of a Florentine mercantile family, Francesco Terriesi (1635-1715) arrived in London in the Spring of 1668, where he would reside for most of the following twenty-one years. There, Terriesi played a key role in the establishment of a chartered Florentine merchant house, giving traders from his homeland direct access to the British markets. In 1670 Terriesi started to work as an unofficial agent of the Florentine government after meeting Grand Duke Cosimo III de’ Medici during the English leg of the Duke’s European grand tour. Terriesi sent detailed and insightful weekly reports to the Duke and the state secretariat, which supplemented those sent by the official Tuscan agent in London.

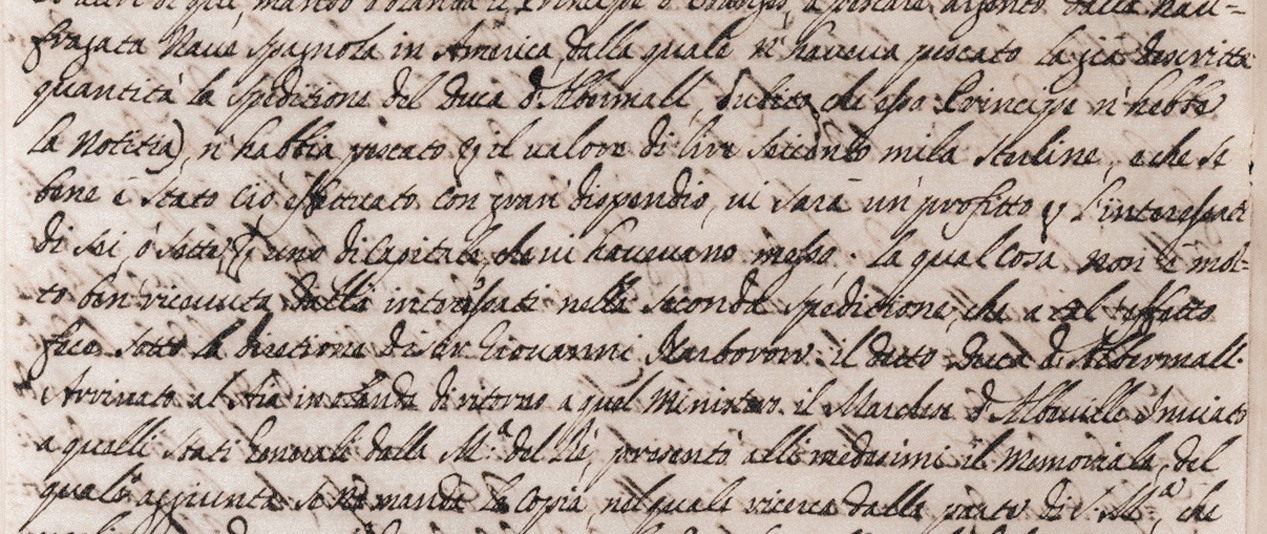

He would not occupy any official diplomatic post until his return to London from Florence in 1678 as the new official Florentine agent. Throughout his stay in London–before and after his official appointment–Terriesi would send a steady flow of letters and avvisi, or newsletters, to Cosimo III and the First Secretary of State Francesco Panciatichi. His weekly dispatches consisted of a short complimentary letter to Panciatichi, followed by a detailed and minutely-written report narrating the main events of the past week. Often, Terriesi attached printed material to fill out his narrative, such as copies of the London Gazette and other pamphlets and printed sheets. In composing his avvisi, Terriesi relied on his extensive network of contacts at King James II’s court and in the London merchant and diplomatic communities, as well as on professional newswriters like the prominent Whig propagandist Giles Hancock.

Terriesi’s avvisi offer a unique perspective of a Roman Catholic diplomat on the world of Restoration England from the heyday of Charles II’s rule to the crisis of succession in the late 1680s and the ensuing Glorious Revolution. The Florentine resident was not just a witness of events, but a player–albeit a minor one–who actively supported James II, and who, at the height of the anti-Catholic riots in London in December 1688, saw his house in Haymarket Square ransacked by the mob.

While Cosimo III’s tacit acknowledgement of William III’s place on the English throne permitted highly profitable commercial exchanges between Tuscany and England to continue after 1688, the diplomatic relations between the two rulers broke down. Terriesi left England in March 1691 to become the Provveditore della Dogana, or Head of Customs, in Livorno.

NEXT: An introduction to the people involved in these maneuvers for the English throne.