2.1 Dering’s Books

Books Worth Keeping

Dering’s activity as a purchaser shows in practice the characteristic traits of print circulation: the texts were dispersed from their place of origin, and brought into different locales that offer new opportunities for correlation. Books of disparate origin were brought together in a single room, enabling new forms of cross-referential study. Dering’s book-collecting produced a family resource that would be passed on from one generation to the next.

To take an important example of how the gathering of books into a library could lead to the generation of new cultural products, Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, published, as the title-page states, “AT OXFORD” in 1621, is a major work whose creation was dependent on the author’s thorough immersion in the holdings of the Bodleian Library. Unless his sources had been assembled under that roof, Burton’s researches for the Anatomy and so his writing of it would have been difficult if not impossible.

The adaptation of Henry IV was prepared by one of the most important book collectors in early modern England. For Dering the concept of a “book” such as might legitimately belong to a gentleman’s library, and therefore the implication of collecting these objects, were both firmly grounded in the practices of his time. However, the sheer volume of books and the prominence of play quartos within his purchases single Dering out as an exceptional collector.

Henry Thomas Ryall, “Sir Thomas Bodley”, nineteenth century line and stipple print, based on an original by Cornelius Janssen van Coulen (born 1593). Folger ART File B668 no.1 (size XS).

Playbooks—that is to say small-format editions of single plays from the professional theatre—were often not regarded as serious literature. The famous and crucial example of a dismissive attitude is found in the book acquisitions policy of the Bodleian Library in Oxford University, which was refurbished and expanded by Sir Thomas Bodley as of 1598.

Early in 1612 Bodley wrote twice to his librarian Thomas James to insist that playbooks should be excluded from the Library:

Sir, I would yow had foreborne, to catalogue our London bookes, till I had bin priuie to your purpose. There are many idle bookes, & riffe raffes among them, which shall neuer com into the Librarie (letter no. 220; 1 January 1612)

I can see no good reason to alter my opinion, for excluding suche bookes, as almanackes, plaies, & an infinit number, that are daily printed, of very vnworthy maters & handling, suche as, me thinkes, both the keeper & vnderkeeper should disdaine to seeke out, to deliuer vnto any man. Happely some plaies may be worthy the keeping: but hardly one in fortie. For it is not alike in English plaies, & others of other nations: because they are most esteemed, for learning the languages & many of them compiled, by men of great fame, for wisedome & learning, which is seeldom or neuer seene among vs. Were it so againe, that some litle profit might be reaped (which God knowes is very litle) out of some of our playbookes, the benefit thereof will nothing neere counteruaile, the harme that the scandal will bring vnto the Librarie, when it shal be giuen out, that we stuffe it full of baggage bookes. (letter no. 221; 15 January 1612)

This policy extended to the play quartos of Shakespeare, whose plays, at the time when Bodley wrote, did not enjoy the cultural status or the promise of educational or moral “profit” to the reader that they acquired later. But a large folio edition asserted a claim not to be a mere riff-raff even if it contained plays performed on the public stage. The Library obtained the folio edition of Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies, at an early date; the purchase was recorded as “Wil. Shakespeare, His works. Lond. 1623” in John Rous’s 1635 Appendix to the catalogue of 1620.1

The Shakespeare Folio was entered in the Stationers’ Register on 8 November 1623 and was available in the bookshops very soon after. In 1610 the Stationers’ Company had agreed to send to the Bodleian a copy of all books entered in the Stationers’ Register,2 so the Library’s copy of the Shakespeare Folio probably travelled from London to Oxford at an early date. But it can scarcely have left London earlier than the two copies that Dering purchased on 5 December and presumably took to his home in Kent.

By December 1623 Dering had already prepared his manuscript of Henry IV, making use of quarto editions. Whereas Bodley saw playbooks as trivial items offering no prospect of edification, Dering was keen to purchase them. But his playbooks do not appear in his library catalogue. This does not mean that Dering attached little importance to the collection that he, in contrast with Bodley, was so keen to build. His determination to collect, and his enthusiasm for making practical use of playbooks for the purposes of performance, are evidence that suggests a personal, positive, and creative engagement with them. Dering may have gained more benefit from his playbooks than from weightier volumes. And their failure to appear in his book catalogue can be explained at least partly by the small format rather than the content. On the other hand, even the Jonson and Shakespeare folios are unlisted in the catalogue.

It should be kept in mind also that the catalogue was compiled later in Dering’s life. It reflected the priorities of a mature man, and it described a family resource intended to continue beyond his lifetime: in his own words ‘to leave this Lieger record to my posterity, thereby to make them to be active-minded in vertue.’3 Negotiation of this issue requires a nuanced approach to the question of cultural value that recognises that book format is significant but not deterministic or definitive, and that personal engagement, financial investment and legacy to the future are distinctly different criteria for determining value.

The primary evidence for the scope of Dering’s library comes from four sources: his manuscript catalogue, his Book of Expenses, his manuscript list of manuscripts, and his Pocket-Book. To these may be added the commonplace book in which he recorded quotations from authors, though it most immediately demonstrates reading rather than ownership. These will be considered in turn. The overall picture they build up is well described by Krivatsy and Yeandle:

Dering had books on history, heraldry, genealogy, law, agriculture, education, mathematics, English, French and Italian literature, the classics, natural history, travel, medicine and above all religion and theology from both Protestant and Catholic presses. The earliest is dated 1495, the latest (of which there are several), 1642. About half were published on the Continent, principally in Paris, Basle and Antwerp. Most were in English and Latin, a few in Greek three in French, one in Scottish, two in Arabic and two in Anglo-Saxon, a language he was at some pains to learn. The evidence for the large number of playbooks occurs in the Booke of Expences.4

The database Private Libraries in Renaissance England contains records of over 600 printed books in Dering’s library, and a large volume of manuscripts survives as well.

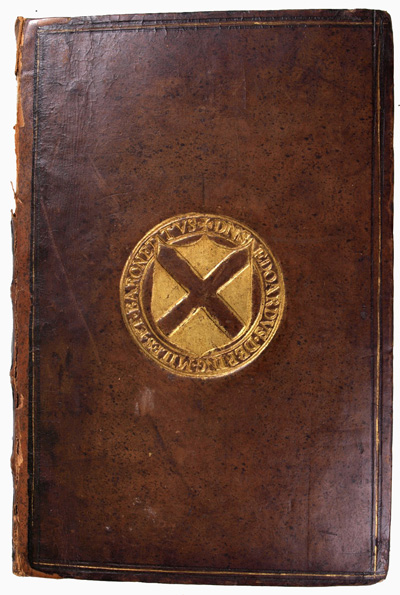

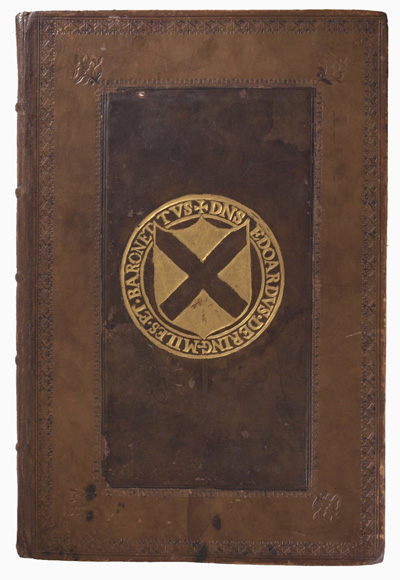

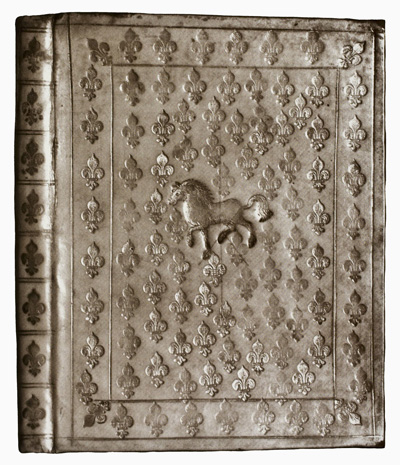

Books could be bound separately from the initial purchase according to the requirements of the new owner. A few volumes from Dering’s library survive and are held in the Folger Shakespeare Library, as illustrated below. They demonstrate that Dering chose good quality leather covers and proudly decorated them with stamps of his coat of arms. On 27 March 1623 Dering had paid £1 for “A print Cutt in brasse for to presse my armes on my booke”. His receipt of his baronetcy in 1627 gave fresh impetus: at this time he bought several further brass stamps.5 There are surviving examples of his saltire stamped in gold and his emblem of the horse, as the following illustrations show. The saltire is found on the Folger copies of Rudolph Hospinian’s De origine, progressu, usu, et abusu templorum, and on the Eton College Library copy of John Guillim’s Display of Heraldry as well as the books illustrated.

Front cover, Dering’s copy of Vindiciæ Ecclesiæ Anglicanæ (1625), stamped with Dering’s coat of arms with motto “Dns Edoardus Dering Miles et Baronettus”. Folger STC 17598 copy 1.

Engraved title page of Thomas Scott, Vox Dei (1624), copy annotated “from the Dering collection”. An emblematic image with Christ standing on Death (a human skeleton), Sin (a serpent with a human head), and Satan (a monster). He holds a triangle with a whole-length figure of James I as Defender of the Faith, surrounded by medallion portraits of his family; in the upper angle of the triangle Charles, Prince of Wales, in armour, tramples on a figure with the heads of the pope and two kings labelled ‘False Universalls’; an armed man stands in each of the lower angles, one trampling on a two-headed figure representing ‘Faction’ and ‘Bribery’, the other on ‘Treason’, a man holding a knife and a pistol; emblems of the British nations, lion, unicorn, harp and dragon in each corner of the sheet” (British Museum, Collection Online: Vox Dei). Dering does not record this title. The book contains an attack on the failed Spanish Match and is virulently anti-Spanish. Folger STC 15432.

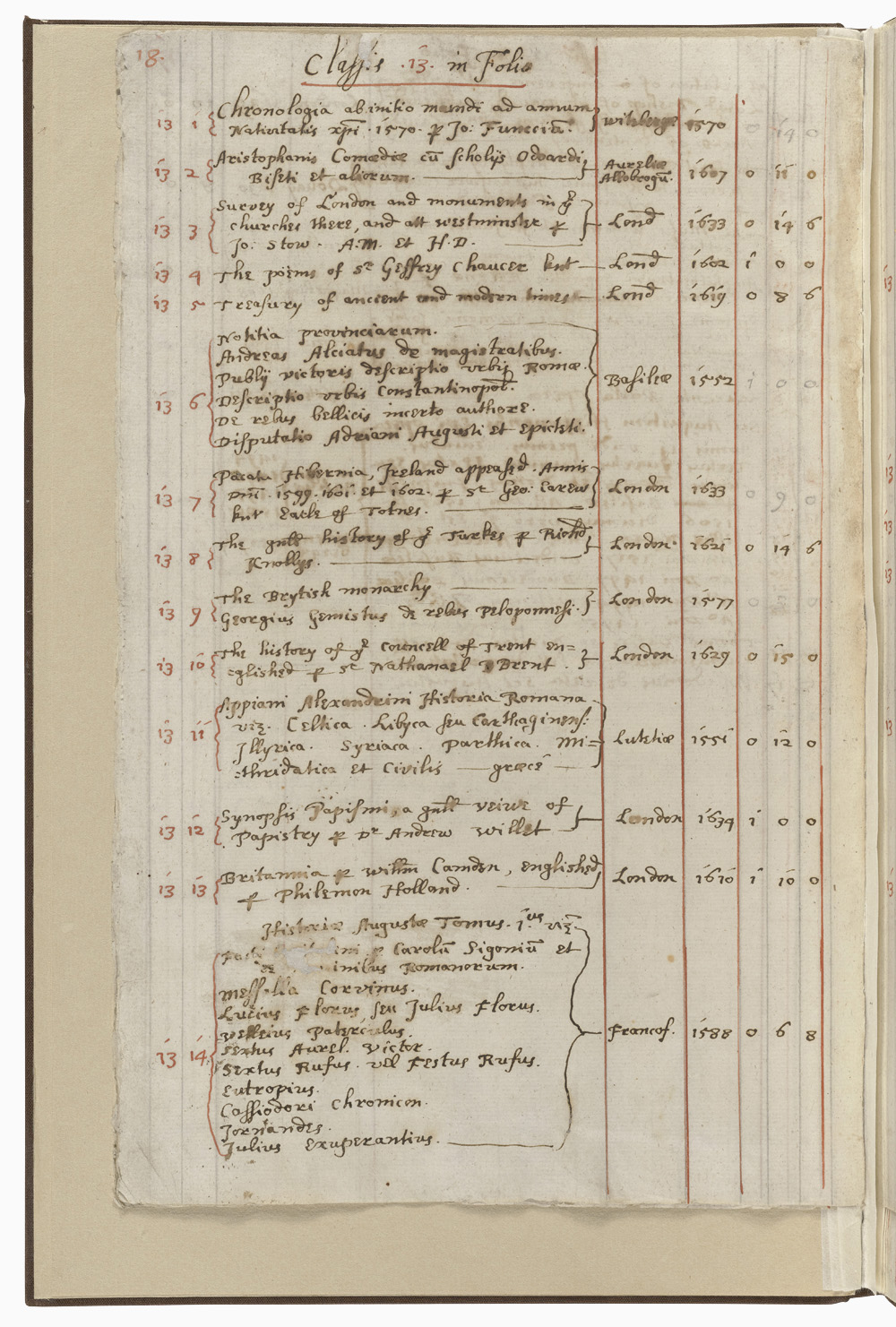

The Catalogue of Printed Books

Books befitting the scholar, in folio format, were more formally recorded in Dering’s manuscript catalogue. It is arranged in an orderly way in columns, the first two showing the classification number and the item number, the next the title, followed by the place and date of publication and the amount Dering paid. There is a separate section on religion and religious history.

The catalogue contains a significant number of items that were either published abroad or issued some years before Dering’s purchase, or both. Book auctions had yet to be established in England but were common in Holland,6 which would also have been on the trade route from the Frankfurt book fair to London. So too was Antwerp, from where number of London booksellers specialised in importing second-hand books.7

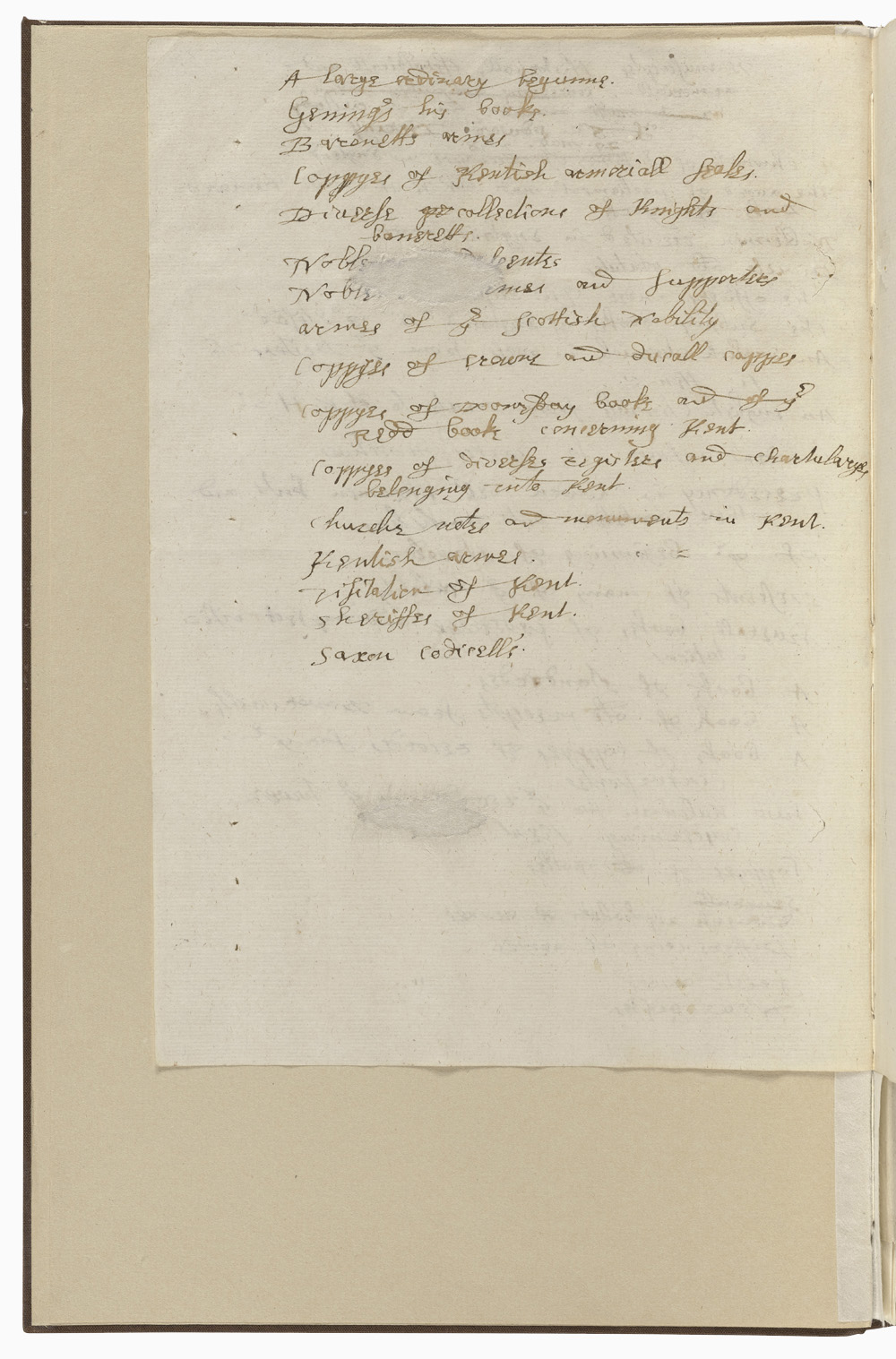

In the leaf preceding the main catalogue of printed books Dering made a less formal note of manuscripts he owned, headed “Manuscripts Historicall, Heraldicall and armoriall, in ye custody of Sr Edward Dering 20. may. 1638.” Thirty-eight items are named, a small proportion of his manuscript holdings. There is no mention of his adaptation Henry IV.

The Book of Expenses

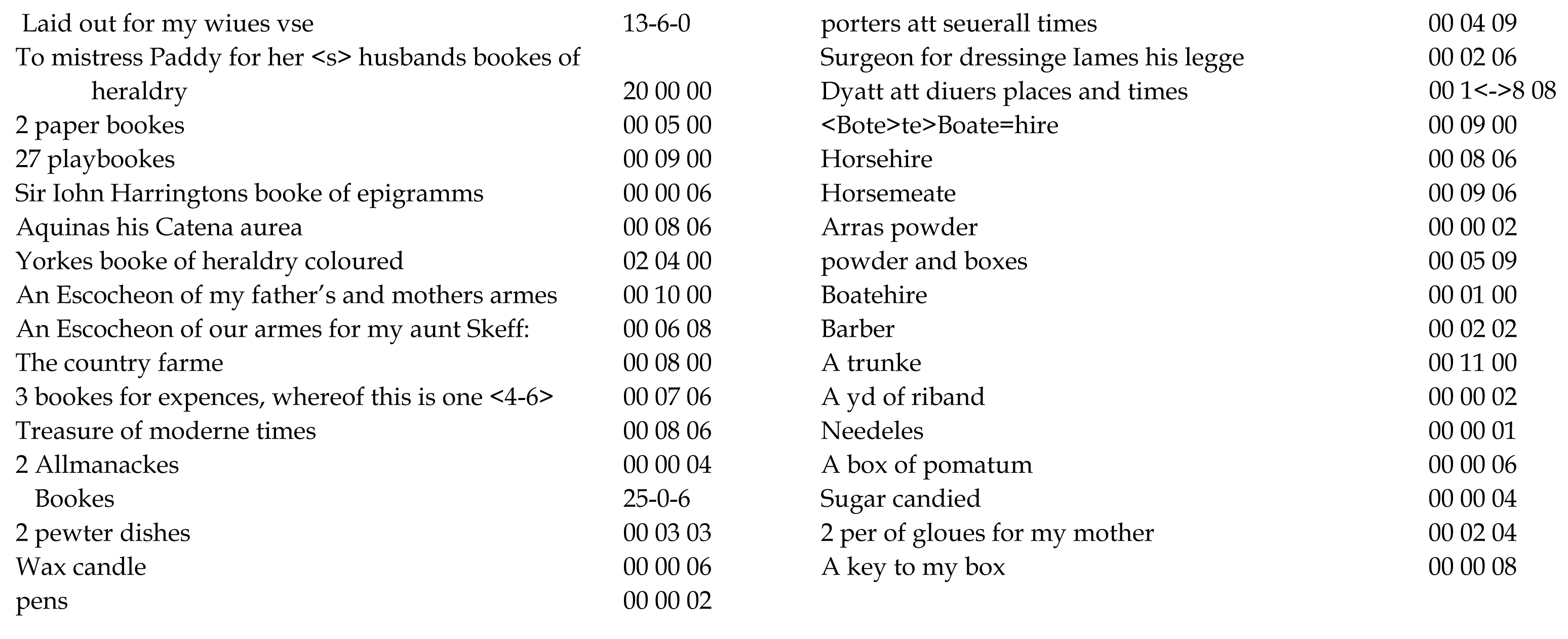

Dering’s account book that he calls the Book of Expenses, covering the crucial period 1617-28, records his purchases in varying degree of detail. This document is so fascinating and rich as a resource illuminating the spending habits of Dering as a country gentleman—typical in some ways, idiosyncratic in others—that it is worth reproducing an extract from it:

This example is copied from Laetitia Yeandle’s invaluable transcript of the entire book, which can be accessed readily from the Kent Archaeological Society.

These payments represent part of Dering’s expenses in the third quarter of 1619, “from michaelmas vnto Newyeare’s day”, a period of outgoings so extravagant that Dering described it as “My desperate q[ua]rter”. It is symptomatic that in that quarter he paid £2 18s 4d for “vse of mony”, interest on a loan: not the only such entry, but the first in the Book. The items listed do not include running costs of household wages, food, and the like. Here, interspersed among payments for clothing, adornments, household goods and services, gifts, and spending money for his wife, are payments furthering Dering’s two hobbies, book collecting and heraldry. These take up a huge proportion of the whole. The exact figures are difficult to calculate as the inset record of £25 0s 6d for books looks like a running total, but that in itself is a very considerable sum, and indeed the largest figure in any one entry in the illustrated period, and one of the larger in the Book as a whole.

Three individual book titles can be identified in this extract:

- “Sir Iohn Harringtons booke of epigramms” (6d): either John Harington’s Epigrams both Pleasant and Serious issued in quarto in 1515 or, perhaps more likely given the date, the 1618 octavo reissue under the title The Most Elegant and Witty Epigrams.

- “Aquinas his Catena aurea” (8s 6d) : St Thomas Aquinas’ Catena aurea, an anthology of commentaries on the Gospels. It was not published in England. This purchase was probably a sixteenth-century edition, as published in Antwerp in 1591 or Venice in 1595. Both were folio volumes.

- “Treasure of moderne times” (8s 6d): an anthology including Spanish humanist Pedro Mexia’s popular miscellany Silva de varia lección, translated by Thomas Milles as The Treasury of Ancient and Modern Times; the first part was published in folio in 1613 and the second in 1619. The sum paid for this work might indicate a bound copy of the shorter and very recently published second part. Both parts were printed and published by William Jaggard whose son Isaac published the Shakespeare First Folio; thus Dering probably frequented the Jaggards’ shop some time before he purchased the Shakespeare Folio.

The titles suggest that at this time Dering was interested in amassing a hoard of philosophical and religious wisdom and sayings. All three books are compilations or anthologies.

Dering’s purchases of playbooks were at times intense, particularly during this period. The twenty-seven playbooks represent the largest single purchase of such books. Relative to the number of playbooks likely to have been available in London bookshops in 1619, the figure is so large as to suggest that some multiple copies of individual plays were involved. But Thomas Pavier’s ten quartos of plays supposedly or actually by Shakespeare became available in 1619. They were printed and possibly co-published by Jaggard, and therefore might have been available at the same shop as The Treasury of Ancient and Modern Times.

Dering’s expenditure relating to heraldry includes the second most costly item, Mistress Paddy’s “husbands bookes of heraldry” (£20), perhaps a collection of books, perhaps sold by a deceased man’s widow. “Yorkes booke of heraldry coloured”, still expensive at a fraction of the cost (£2 4s) is most likely A Catalogue and Succession of the Kings, Princes, Dukes, Marquesses, Earles, and Viscounts of the Realme of England, since the Norman Conquest, to this present yeare 1619. Together, with their Armes, Wiues, and Children: the times of their deaths and burials, with many their memorable Actions. Collected by Raphe Brooke Esquire, Yorke Herauld. This book too was printed and sold by Jaggard. ‘Coloured’ suggests colouring by hand of the coats of arms printed in the book. Dering must have paid extra for the colouring. This purchase was quickly followed by two expenditures on family escutcheons. Dering’s interest in heraldry is discussed further here.

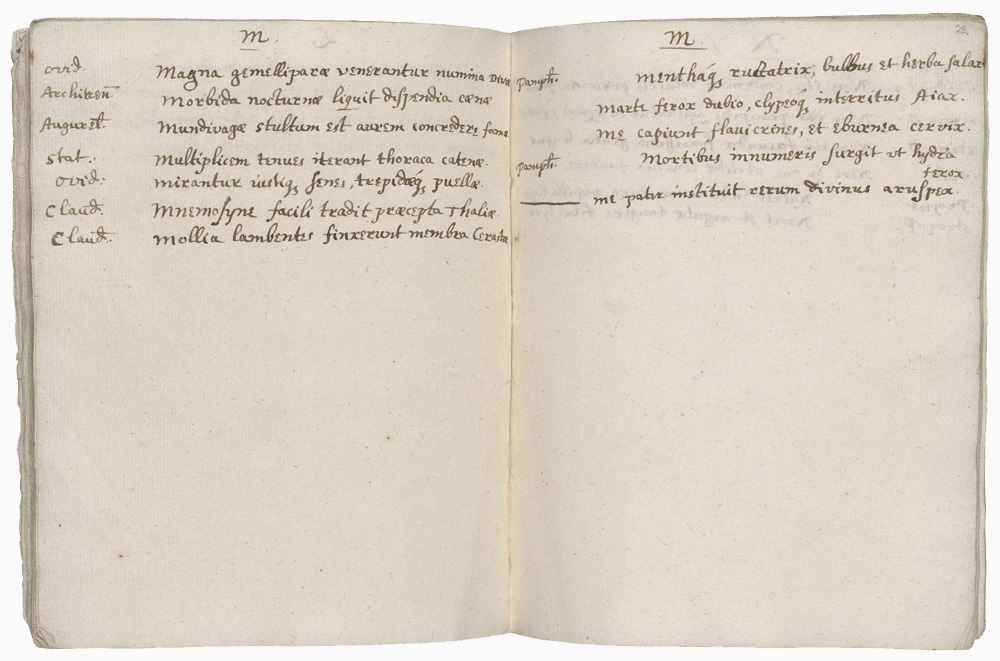

The Commonplace Book

Dering’s reading (as distinct from book-buying) can be chartered further by consulting his commonplace book of Latin quotations. The correspondence is far from exact, as Dering evidently began his commonplace book in his youth, before many items in his library would have been purchased. According to Robert J. Tallasken, his favoured authors for the purpose of commonplacing, in order of frequency of quotation, are the Roman poets Publius Naso Ovidius (Ovid, almost everyone’s favourite) and Claudianus (Claudian), the Renaissance poet Baptista Mantuanus, and the Roman poets Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil), Marcus Valerius Martialis (Martial), and Publius Papinius Statius.8 These are some of the most usual Latin authors to be cited or quoted by early modern writers.

Dering’s library is known to have held works by a number of the authors quoted in the commonplace book, including some of those Dering quoted less frequently. Of the writers he quotes, he owned books by the Renaissance historian of ancient Rome Johannes Baptista Egnatius (Giovanni Battista Egnazio), Claudian, the Renaissance humanist Desiderius Erasmus, Roman poet and philosopher Titus Lucretius Carus (Lucretius), Roman poet and astrologer Marcus Manilius, Martial, Ovid, and Virgil (though the edition of Gavin Douglas’s translation of the Aeneid into Scots is not the source of Dering’s Latin quotations from that work).

How are Books Useful?

A year before his adaptation of Henry IV, Dering spent 8d on “a locke for my study doore”, the first of a series of expenditures to equip his study as a library, a place where books could be safely stored and conveniently read.

Not surprisingly, Dering had a strong reputation as a man of learning. According to Wlliam Dugdale he was “an excellent Antiquarie.”9 To John Vicars writing in 1642 he was “a scholar and witty acute rhetorician” and to compilers of a report for Parliament “a man of mark and eminency, of wit, learning, and zeal.”10

Dering’s antiquarian scholarship was crucial to his pursuit of ancient family history and his broader interest in heraldry. His speeches and other political writings reflect his knowledge of law and English constitutional history. His published anti-Catholic works show ample evidence of his erudition in matters of religious doctrine. There is, therefore, a real sense in which the books in his library helped to shape and deepen the most fundamental aspects of his career and identity.

Much the same applies to the humble playbooks that brought the textual resources of the London theatre to his house in Surrenden. But the adaptation of Henry IV required no reading beyond the two play quartos (and probably the 1600 or 1602 edition of Henry V used for Dering’s alteration of the final page). Just as books divide between the large, expensive, and scholarly volumes recorded in his catalogue and the humbler playbooks mentioned without title in his Book of Expenses, Dering’s use of these books divides between the serious and outward-facing aspects of his scholarly life and the unresearched entertainment planned for his friends and household.

PREVIOUS: Learn about Dering’s vast collection of books and plays.

NEXT: Read about Dering’s collection of plays and playbooks.

- Rous, Appendix, 172.

- Hanson, “The Shakespeare Collection,” 78. See image and comments from the Bodleian Libraries.

- Krivatsy and Yeandle, “Sir Edward Dering,” 149.

- Krivatsy and Yeandle, “Sir Edward Dering,” 142.

- Krivatsy and Yeandle, “Sir Edward Dering,” 143.

- Lankhorst

- Roberts, 162

- Robert J. Tallaksen, private email, 2 May 2018.

- Wright, “Sir Edward Dering,” 373.

- Peacey, “Sir Edward Dering,” 955, 979.