4.2 The Protestant Moment

At a point where Dering introduces a major cut in his source text 2 Henry IV he produces a join that is distinctly clunky in terms of the flow of the text. Yet is distinctly purposeful in terms of the play’s militaristic theme:

King: I will take yowr counsell

And weare these inward warres once out of hand

We would deere lords unto the holy land:

King: Now my lord: if God doe give successful end

To this debate that bleedeth at our dores:

We will our youth leade on to higher feilds

And drawe noe swords: but what are sanctified:

(fol. 48r)

Elsewhere in the manuscripts there are two clear-cut examples of what may be described as “literary” alterations. These too relate to military issues. Here we find additions that have no bearing on the shortening of the text, or the number and disposition of dramatic roles.

The first rendition of the manuscript had already introduced a few local literary changes. For instance on the first page the printed copy read:

No more the thirstie entrance of this soile,

Shall daube her lippes with her owne childrens blood:

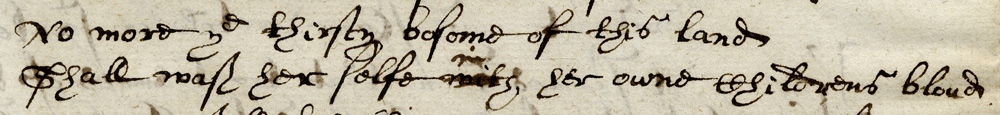

The Dering transcript alters the disturbingly violent grotesquery of Shakespeare’s image into the more decorous if less coherent:

No more ye thirsty bosome of this land

Shall wash her selfe

within her owne childrens bloud

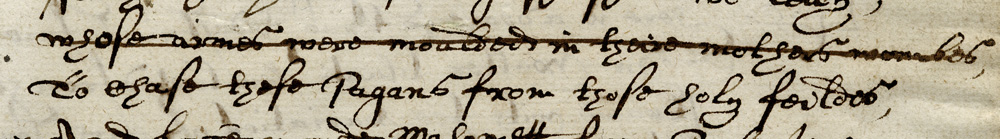

In the same vein, after copying out the line “whose armes were moulded in their mothers wombes,” higher up the page, Dering later deleted it.

This offers a clear indication of what disconcerted him about the “thirstie entrance”. There is perhaps a sense of literary decorum at work in another alteration Dering made to his own transcript of the first page. Here, following copy, Dering initially wrote, immediately before the “thirsty bosome” line:

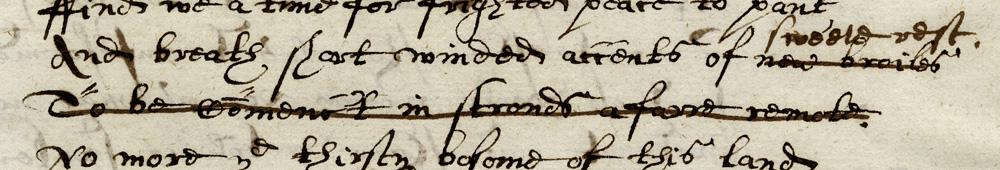

And breath short winded accents of new broiles

To be co[m]menc’t in stronds afarre remote.

He later crossed out “new broiles / To be co[m]menc’t in stronds afarre remote.” and replaced it with “sweete rest”, thus giving the King the breathing space that Shakespeare had so uncomfortably denied him: “And breath short winded accents of sweete rest”.

However, more than decorum is at stake in this particular revision. It relates to the first of the two more substantial additions that amount to a designed literary expansion introducing new ideas relating to the wider field of national and international politics and public action.

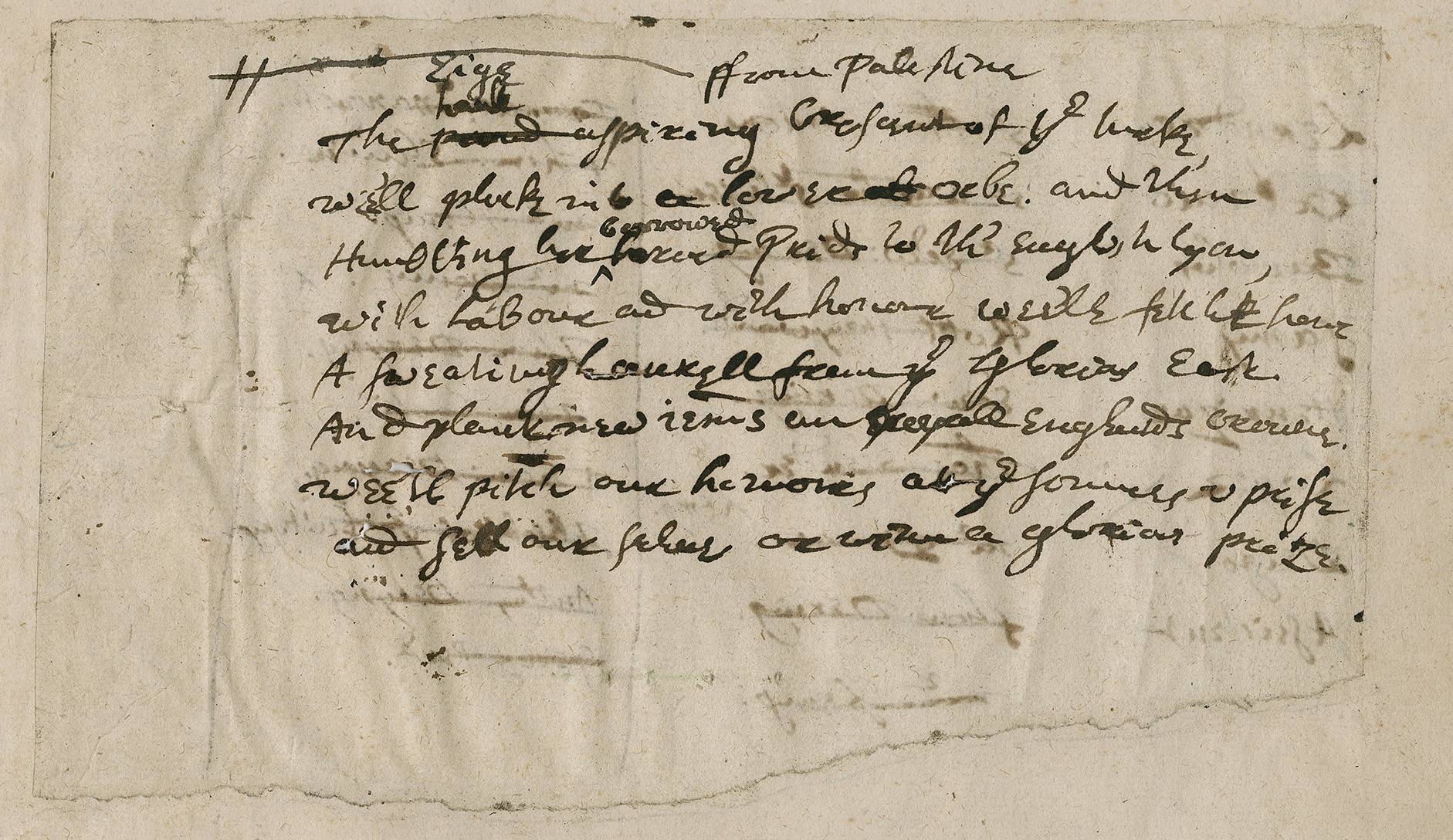

The first of these passages expands on King Henry’s ambition to “chase these pagans in those holy fields” of Palestine (1 Henry IV 1.1.24), or, as Dering more ambitiously has it, “To chase these Pagans from those holy feildes”. Writing on the reverse side of the Spanish Curate slip, Dering continues:

[And force proude Mahomett] from Palestine

The high aspiring Cresant of the turke,

Wee’ll plucke into a lower orbe: and then

Humbling her borrowed Pride to th’ English lyon,

With labour and with honour wee’le fetch there

A sweating laurell from the glorius East

And plant new jemms on Englands crowne.

Wee’ll pitch our honores att the sonnes uprise

And sell our selves or winn a glorious prize.

As compared with the shorter and more religiously motivated words of Shakespeare’s king, these lines of strained conceit are notably vainglorious. They therefore give even heavier irony to the King’s immediate self-correction, “But this our purpose now is twelve-month’s old, / And bootlesse ’tis to tell you we will go”. There are other effects. The added lines anticipate Hotspur’s ambition “To pluck bright honour from the pale-faced moon” (1.3.200; Dering retains the line). The same verb “pluck”is applied to both moons. The connection between the Islamic “Cresant” and Hotspur’s “pale-faced moon” is reinforced by the repeated word “glorious”: Shakespeare likewise repeats the word in a single speech in 1 Henry IV (“glorious day”, 3.2.133; “glorious deeds”, 146; “glorious deeds”, 148; also “he shall render every glory up”, 150). These phrases all refer to Hal’s intent to redeem himself by seizing Hotspur’s “honour and renown” (139). Dering’s addition clearly suggests a similarity between the incursions of Islam in the east and Hotspur’s “high aspiring” northern rebellion against the crown. The play’s Jerusalem, as the King will discover as he dies, lies not in the Near East but in his own palace (2 Henry IV 13.360-8/4.3.360-8). These lines help to cement the two original parts into one.

And they anticipate another moment: Hal’s contrast between himself as monarch and the Turkish Sultan towards the end of Part 2:

This is the English not the Turkish court;

Not Amurath an Amurath succeeds,

But Harry Harry.

2 Henry IV, 15.47-9/4.3.47-9

Due to the heavy cutting, Hal’s speech occurs in the final scene of the Dering play. But they recall Dering‘s addition to the opening speech. From the perspective of 1623, though the Turks had recently been supporting the Protestant Hungarian revolt against Austria, they were often analogically correlated with the Catholics as the enemies of true religion. In 1610, for instance, Hugh Broughton had referred to the Protestant “reuiuing of the Gospell” against both the Pope and the Turk (A Revelation of the Holy Apocalypse, L1v), and in 1625 urged remembrance of the Last Judgement as enabling endurance “when we are crossed and cursed of Turke and Pope” (An Exposition of the Second Epistle of the Apostle Paul to Timothy sig. Ee4r). In 1613 Henry Ainsworth quoted at length John Bale’s earlier assertion that “The Turk is out of the Church, and so in truth is the Pope”, both being “malignant Ministers of Satan” (An Animadversion to Mr Richard Clyfton’s Advertisement,sig. O1v-2r). In 1615 Thomas Drax referred to “Christs Arch-enemies, the Turke and Pope” (An Alarum to the Last Judgement, sig. B3r). In 1619 Thomas Dighton proclaimed “the promise of Christ” to “conuert Turke and Pope too” (The Second Part of a Plain Discourse, sig. C5v). In 1621 even the high-church Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud accounted “both the Pope and the Turke” as “our two great enemies” (A Sermon Preached before His Majesty, sig. D3v).

It is no accident that the prize for defeating the Turks in the first of Dering’s additions is described as “glorious”. In Dering’s published writings this word was always applied to or associated with the Protestant Reformation: “This would be glorious for us and for our Religion” (A Collection of Speeches (1642), 77), “the most glorious hopes of a full and blessed Reformation that ever lay before a Parliament” (136), “the losse of such a glorious Reformation” (165). The analogue between the historical Crusades against the Muslim infidel and the present-day Protestant wars of religion was an established point of reference.

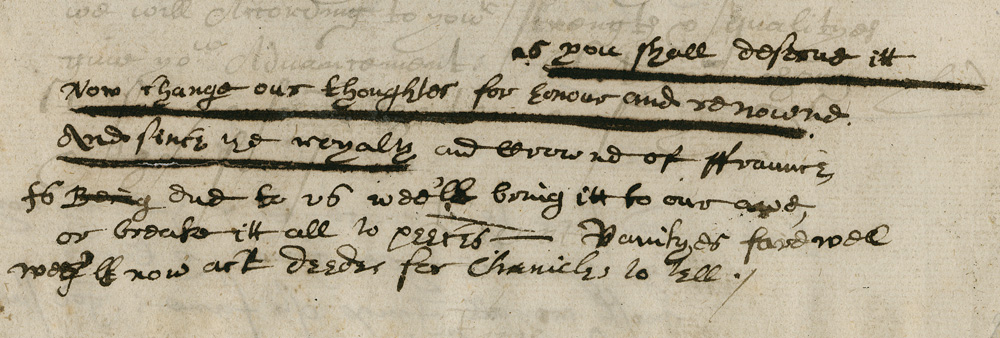

Dering’s second alteration is written in heavy black ink directly over the top of and below the scribe’s paler script of the play’s final lines. In it, he completes his framing manoeuvre by returning to the issue of military intervention on foreign soil:

as you shall defend itt

Now change our thoughtes for honour and renowne.

And since the royalty and crowne of Fraunce,

Is due to us wee’ll bring itt to our awe,

Or breake itt all to peeces. Vanities farewell

Wee’ll now act deedes for Chronicles to tell.

(fol. 55v)

The Marlovian aspiration and violence have returned; only the target has changed: not the Turks but the French. Dering is of course echoing Henry V’s aggressive words before he confronts the ambassadors from France in Henry V:

France being ours, we’ll bend it to our awe,

(1.2.224-5)

Or break it all to pieces.

Or, as given in the most recent edition of Henry V, the quarto of 1619 (dated 1608 on the title page):

France being ours, weel bring it to our awe,

Or breake it all in peeces:

(sig. A4r)

Whereas Dering and the Folio read “to peeces,” all the quartos Dering might have purchased have “in peeces.” Dering’s anticipation of the Folio reading may be a mere coincidence, but it is at least possible that he remembered the reading from the stage, or that he copied it into a notebook during performance.

As compared with Shakespeare’s play, Dering’s Henry lacks Shakespeare’s Henry’s awareness of other possible outcomes. For example, the following lines are cut:

Or lay these bones in an unworthy urn,

Tombless, with no remembrance over them.

Dering’s militaristic book-ending of the play, lacking such intellectual flexibility, shows the imprint of historical circumstances at a time of heightened ideological militarism. The “honour and renown” Hal sought by defeating Hotspur has been translated to his anticipated defeat of the French and hence, in the context of the religious wars of the 1620s, echoes the calls to support the Protestant cause. Thomas Middleton, when recently adapting Measure for Measure, had given the play a new topicality in his revision of 1.2 by relating it to events of the Thirty Years War.1 Dering might have seen this revival on stage in late 1621 or subsequently. He follows Middleton’s example by heightening his audience’s awareness that this is a time of European war. James I’s son-in-law, the Elector Palatine and King of Bohemia Frederick, had been irremediably defeated at the Battle of the White Mountain in 1620, and in France the Protestant Huguenots had suffered defeat at the Siege of Montauban in 1620 and the Battle of Saint-Martin-de-Ré in 1622. The defeat of Frederick by the Catholic Habsburg forces was decisive in rallying the English Protestant faction into calling for English engagement in the religious wars. The 1621 Parliament attempted to debate war with Spain. These were events that attracted huge interest in England, as can be measure by the number of references to the Palatinate in early modern printed books rising from none at all in the first decade of the 17th century to forty seven in the second decade to 859 in 1620-29.

Meanwhile, King James’s aim was to pursue peace with Spain and the Papacy. This policy was widely regarded as a betrayal both of the Protestant cause and of his defeated daughter Elizabeth and son-in-law Frederick. At the time of Dering’s adaptation, Prince Charles and George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, were in Madrid, having travelled there in disguise. Their aim was to finalize the proposed Spanish Match between Charles and the Infanta, which would have ensured peace with Spain and kept England safely out of the growing European conflict. This proposed marital alliance with Spain was unpopular, and Charles and Buckingham’s return empty-handed in October 1623 would be greeted with wildly enthusiastic celebration in London.2 These events had yet to unfold when Dering prepared his adaptation of Henry IV, but even before the Spanish Match fiasco a wide political-religious divide had opened up between the Protestant war faction and the King’s supporters in his pursuit of peace with the Catholic powers.

The politics of the Dering additions suggest that his sympathies lay with the war faction. Exercising the royal prerogative, James I had explicitly forbidden open debate on foreign policy, both in Parliament and in the country at large. When the 1621 Parliament presented a protestation affirming that free speech was an “ancient and undoubted right received from our ancestors”, as Andrew Thrush relates, James “tore the Protestation from the Commons Journal and ordered the imprisonment of its principal author, Sir Edward Coke. Further arrests of leading Members of the Commons followed. Early in the New Year James, after announcing to his Council that he would have no more to do with parliaments, dissolved the Parliament – now downgraded by royal proclamation to the status of a convention – with immediate effect.3 With the prohibition on discussing foreign policy reaffirmed, Dering was taking the usual recourse of joining the debate nevertheless by citing history analogically, taking the added precaution of keeping the matter within the safe context of a Shakespeare history play, and restricting his engagement to the privacy of his own home.

Michiel van Miereveld, “Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia” (after 1623), oil on panel. Folger FPb54. Elizabeth (1596-1662) was daughter of James I of England and consort of Frederick V, Elector Palatine 1610-1623, King of Bohemia 1619-20, and leader of the Protestant Union.

Dering’s overall intention is therefore clear: by modifying the moments of inception and closure he changes the way the play addresses its audience and engages with its moment in time. In other words, his interventions are comparable with the practice of supplying a new prologue and/or epilogue for the revival of a play by a professional company–or perhaps even with a book-collector’s redefinition of the reading context in acts such as collocation through binding and personal inscription. The culture of private household performance invites further comment. Dering’s activity as provincial gentleman-amateur playmaker is part of a wider private dramatic activity in early modern households as seen, not only in the more fragmentary evidence of his other productions such as The Spanish Curate and Philander, in the Elizabethan entertainments discussed by Elizabeth Zeman Kolkovich and, in the Jacobean period, the plays of William Percy, who claimed that his plays are based on originals that had earlier been performed by Paul’s Boys, and John Newdigate, whose The Emperor’s Favourite performed probably at Arbury Hall in Warwickshire satirizes Buckingham;4 Dering visited Arbury shortly after adapting Henry IV, on 23 April 1623 (“Booke of Expenses,” fol. 30r). More significant to the Protestant politics of Dering’s adaptation, the symbolic figurehead of English Protestant militarism Queen Elizabeth of Bohemia is known to have arranged for a performance of Francis Beaumont’s and John Fletcher’s The Scornful Lady at her court in exile at The Hague; it is possible that it was produced by Robert Honywood, a member of Dering’s cast for The Spanish Curate.

Dering’s Henry IV may be compared with Globe plays such as Sir John van Olden Barnavelt and A Game at Chess as political dramas of the late Jacobean period that contributed provocatively to the new polemics of religious warfare. As has been suggested, it can be correlated particularly with Middleton’s adaptation of Measure of Measure, as an adjustment of an outdated Shakespeare play to meet the political mood of the early 1620s. Set alongside each other, these two adaptations suggest that the early 1620s begin a revisionary politicization of earlier drama, long before well recognised examples such as Humphrey Moseley’s pro-royalist publications of plays, most notably the Beaumont and Fletcher Folio of 1647, two years before the execution of King Charles I. This and subsequent Moseley play publications, discretely protesting against the closure of the public theatres in 1642, were oppositional to the Presbyterian and republican regime of the Interregnum. In contrast with these later initiatives, both Middleton and Dering, by adapting his plays, co-opted Shakespeare to the Protestant cause.

PREVIOUS: Learn about how Dering staged some performances in his home.

NEXT: Who may have performed in Dering’s household performances?