1.1 A Jacobean Polymath

Scholar

Sir Edward Dering (1598-1644) is best known as a book-collector, antiquarian, genealogist, and politician. In his earlier life he was a playgoer in the London theatres and an avid collector of books in the London bookshops. He built up one of the most extensive collections of books of the period. These included the largest known collection of plays. His most significant purchases were carefully recorded in a manuscript catalogue. Small-format playbooks not included in the catalogue are mentioned in his more general accounts in his Book of Expenses, a detailed record of non-routine expenditure covering the period from 1617 to 1628. But they are usually listed generically as “playbooks” without divulging their titles. Most of his known books are more impressive works in folio format, including many in Latin. They cover subjects including jurisprudence, religious doctrine, religious history, and antiquarian studies. But Dering was also the earliest known person to buy the Shakespeare First Folio: two copies for £1 each late on 5 December 1623; he bought Ben Jonson’s 1616 Folio collection on the same day.

Amateur Playmaker

Between 1619 and 1624, and so mainly before his purchase of Shakespeare and Jonson in folio, Dering built up an extensive library of play quartos. His interest in theatre led him in 1623 to construct his version of Shakespeare’s two Henry IV plays as a single work for performance by members of his household along with wider family members and friends. He also prepared a staging of John Fletcher and Philip Massinger’s The Spanish Curate, as is evidenced in the list of roles and performers he wrote in a slip belonging with the Henry IV manuscript. His purchase of six copies of the quarto of A Merry Dialogue between Band, Cuff, and Ruff, a comedy performed by students at Cambridge, suggests another planned home performance.

A few years after these productions based on established dramas, Dering thought he would try his hand at writing a play of his own. This is known to us through the manuscript usually known by the unauthoritative title Philander King of Thrace, but more accurately called Aristocles, which outlines the envisaged play’s characters, setting, and plot.

Dering may also have planned to stage a production of Love’s Victory (c. 1618), a surviving play written by the author and literary patron Lady Mary Wroth, niece of Sir Philip and Mary Sidney. It survives in two manuscripts, one of which (Huntington HM 600) is evidently a manuscript from the Dering collection1—though it is not in Dering’s hand. Wroth probably wrote the play for performance at Penshurst Palace in Kent, where Dering may have seen it performed. Events such as this may have stimulated his own interest in staging plays. If, hypothetically, there had been a staging of Love’s Victory at Surrenden House, it may have been a forerunner of his other productions.

Local Administrator

Title page of judge and politician Sir Oliver St. John’s speech against the ship money tax. Folger L.f. 166.

Dering’s successes in obtaining office and advancement owed much to his influence with King Charles’s favourite the Duke of Buckingham, who was distantly related to his second wife Anne, daughter of Sir John Ashburnham. Dering was created Baronet on 1 February 1627. He was appointed as lieutenant of Dover Castle in 1629. In this role he was rigorous in enforcing the controversial tax known as ship money, which enabled Charles I to rule without financial support from Parliament.

Genealogist

Dering’s sense of himself as a knight and gentleman was deeply rooted in his awareness of past history, an awareness that informs his interest in Henry IV. But where Shakespeare was an astute populist observer, Dering was a participant, a member of the landed elite who took his position and responsibilities seriously. This seriousness reflected itself in various ways, including his responsibility to his voting constituents (all local land-owners), as Member of Parliament for Hythe, and specifically through his engagement in the politics of the Long Parliament. Perhaps of still greater importance to Dering, and less flattering to him, was his fascination with heraldry: the study of the lineages of the gentry and aristocracy, and of the armorial emblems that affirmed them.

This preoccupation was widely shared among the English elites, and connected the growing interest in antiquarian history with claims to prestigious ancestry that could be used as a lever towards influence beyond the local community. Dering’s interest was, even by the standards of the period, extravagant.

While lieutenant of Dover Castle, Dering acquired the medieval roll of heraldic emblems that was prepared in the 1270s and that now bears his family name. He altered it after 1638, by removing the coat of arms of Nicholas de Criol and inserting his own coat of arms, under the name of a fictitious ancestor named “Ric[hard] fi[t]z Dering”.

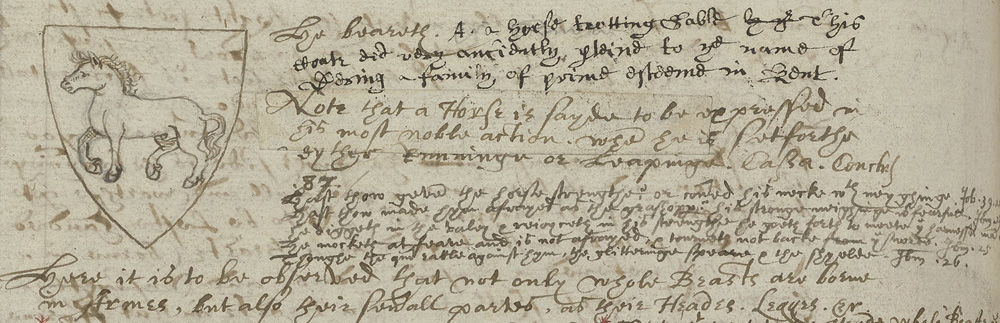

His interest in excavating and enhancing his family pedigree is witnessed further in his purchase of a large manuscript of heraldry illustrated with sketches of coats of arms by John Guillim (1550-1621). A note on the flyleaf “From the Surrenden Library” is written in same hand (19th century?) as the index of family names added at the beginning. This is a variant text of the work of 283 folio pages and over 500 woodcuts first published in 1610 and reissued in 1611 as Display of Heraldry, a book that became the standard reference work on the topic for many years. Dering also purchased the printed version of the 1632 edition for 10 shillings; his copy, bearing Dering’s armorial stamp, is held at Eton College Library. But the manuscript is especially interesting because it allowed the owner’s annotations to blur into forgery. In the manuscript, Dering’s escutcheon of the horse appears on p. 50:

This image and the commentary on it are not found in the printed editions. In the manuscript, the top three lines of writing are mostly in a different hand; they read “a horse trotting Sable by ye This Coate did very anciently p[er]taine to ye name of Dering a family of prime esteeme in Kent.” The hand is evidently that of Dering himself as he inserts text that emphasizes the antiquity and prestige of his family.

PREVIOUS: Learn about Sir Edward Dering and the history of the Dering Manuscript.

NEXT: Learn about the Henry IV manuscript that Dering owned and annotated.