Shakespeare and Young Churchill

A Schoolboy’s Shakespeare

Shakespeare was part of Churchill’s life from the time he was a boy. At home he played with toy theaters and toy soldiers, activities that would shape his later thinking about the theater of war.

Shakespeare was part of Churchill’s life from the time he was a boy. At home he played with toy theaters and toy soldiers, activities that would shape his later thinking about the theater of war.

At the age of thirteen Churchill entered Harrow, one of the top boarding schools for upper-class boys in England. There he competed twice for the Shakespeare Prize, both times coming close but not winning. After the first time in 1888, he wrote to his father, Lord Randolph: “We had to learn & work up the notes in Merchant of Venice, Henry VIII, Midsummer Night’s Dream. I came out 4th for the Lower School.” The emphasis on speaking the lines as a way of learning Shakespeare was typical of the period, but also obviously affected Churchill’s sense of the rhythm and persuasive power of speech which carried into his later life.

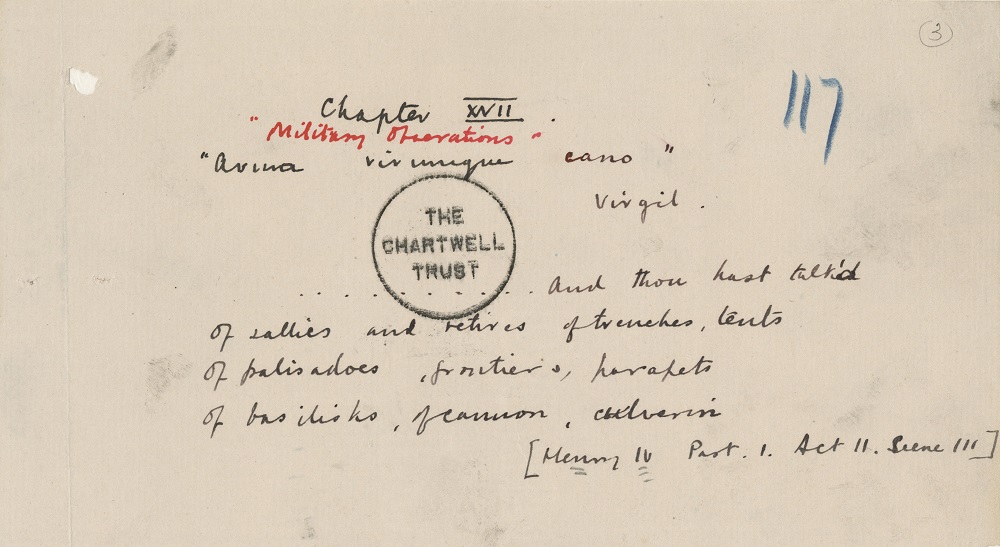

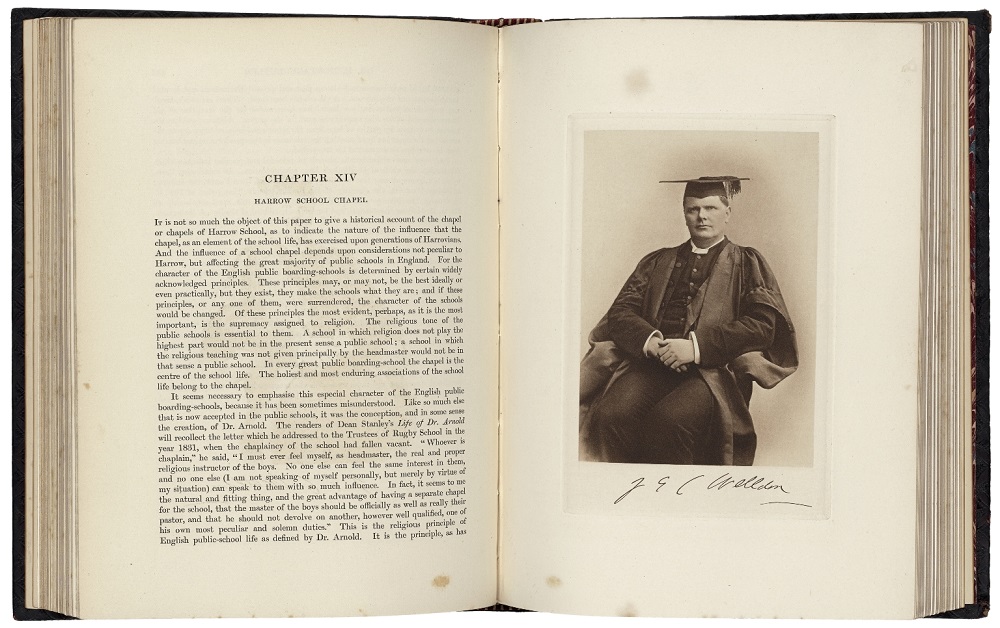

“Harrow School”

Ed. Edmund W. Howson and George Townsend Warner. London: E Arnold, 1898

(LF795 H3 H7. Folger Shakespeare Library)

“Julius Caesar” by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Edited by E.M. Butler, M.A. assistant master at Harrow School. London: E. Arnold, 1896

School editions of Shakespeare were used to spread notions of British superiority throughout the Empire. Students would have learned from this edition that rebellion is to be discouraged; “the settled course of established authority cannot be permanently altered by a few enthusiasts and discontented spirits.”

(PR2756.A81 Sh.Col. Folger Shakespeare Library)

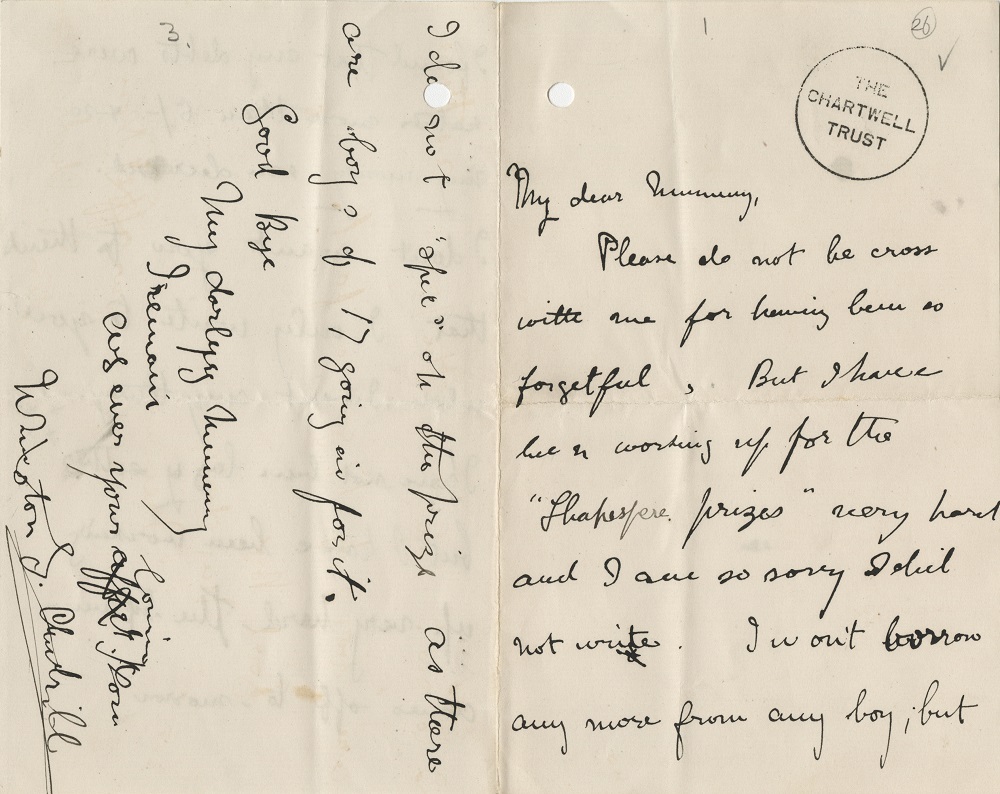

Letter from Winston Churchill to Lady Randolph Churchill

October 23, 1888

Churchill writes to “My dear Mummy,” saying “I have been working up for the ‘Shakespere prizes’ very hard and I am so sorry I did not write.” Unfortunately, he was not successful on this try.

(CHAR 28/15/26. Churchill Archives Centre © The Estate of Winston S. Churchill)

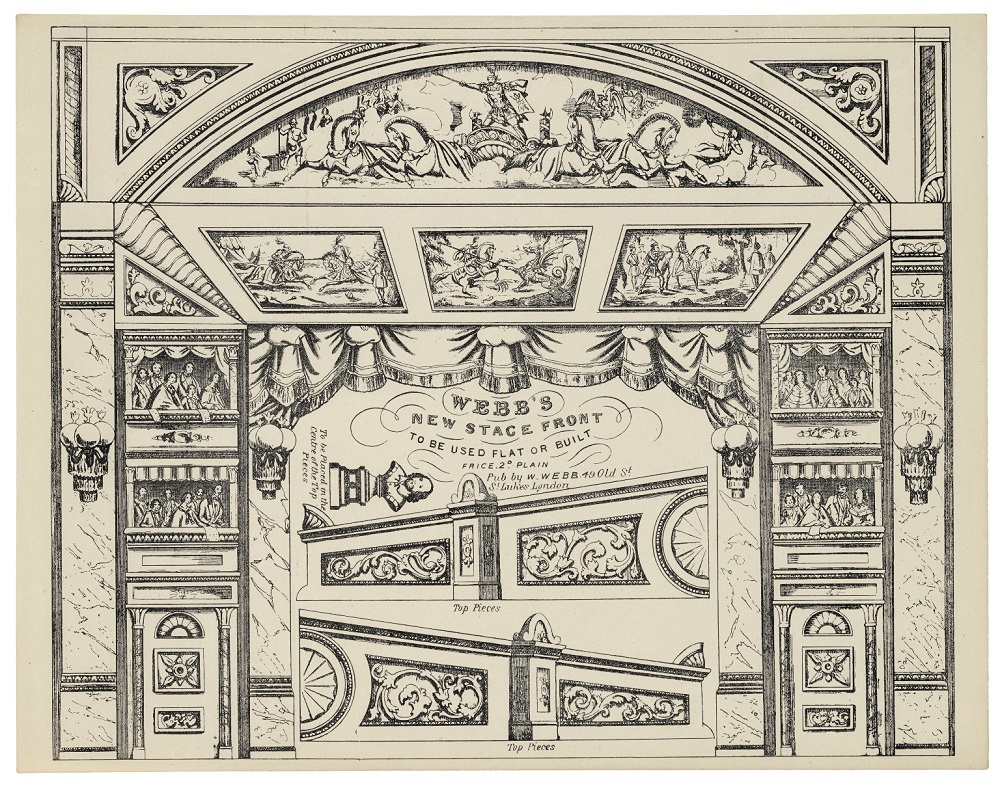

A Child’s Toy Theater

“Webb’s New Stage Front” London: W. Webb, (1880)

Churchill would have bought this kind of uncut, uncolored sheet that could be folded into a toy theater when he visited Webb’s toy store in London. It includes a tiny bust of Shakespeare.

(ART 265172. Folger Shakespeare Library)

Webb’s Toy Theater

Shakespeare’s All the Rage

Churchill’s mother, Lady Randolph Churchill, loved the theater, enjoyed writing plays, and was one of the stars of London society. An avid theater-goer, she organized grandiose fundraising events for a National Theatre and National School of Acting.

After her husband, Lord Randolph, died in 1895, Jennie Churchill married George Cornwallis-West. She organized a grand Shakespeare Ball in 1911 to raise funds for a new National Theatre. A thousand or so guests, richly dressed as Shakespearean characters, joined King George V and Queen Mary at the Royal Albert Hall. The souvenir book for the ball includes pieces written by George Bernard Shaw and G.K. Chesterton, well-known playwrights and essayists.

In 1912, Jennie Churchill followed this event with a second extravaganza — a festival that turned Earl’s Court into a sort of Shakespearean Disneyland with recreations of buildings from Elizabethan times. She applied to her friend Shaw for help in understanding insurance requirements for the event. Feeling inadequate on financial issues, Shaw wrote a long footnote about his work on Irish home rule, which Winston was backing in Parliament, and invited her and Winston to lunch. The Shakespeare festival was not as successful as the ball, but Jennie Churchill, a keen theater-goer, remained convinced that the country needed a National Theatre and National School of Acting.

The Shakespeare Ball

Shakespeare Memorial Souvenir of the Shakespeare Ball

Edited by Mrs. George Cornwallis-West. London; New York: F. Warne & co., 1911

This souvenir volume contains photographs of many of those who attended the ball in Shakespearean costumes. Churchill’s mother writes in the Prologue that all who subscribe to the book should know “that each has individually contributed a stone to the building of the proposed [Shakespeare] Memorial [Theatre].”

(ART Vol. f231 front outside cover. Folger Shakespeare Library)

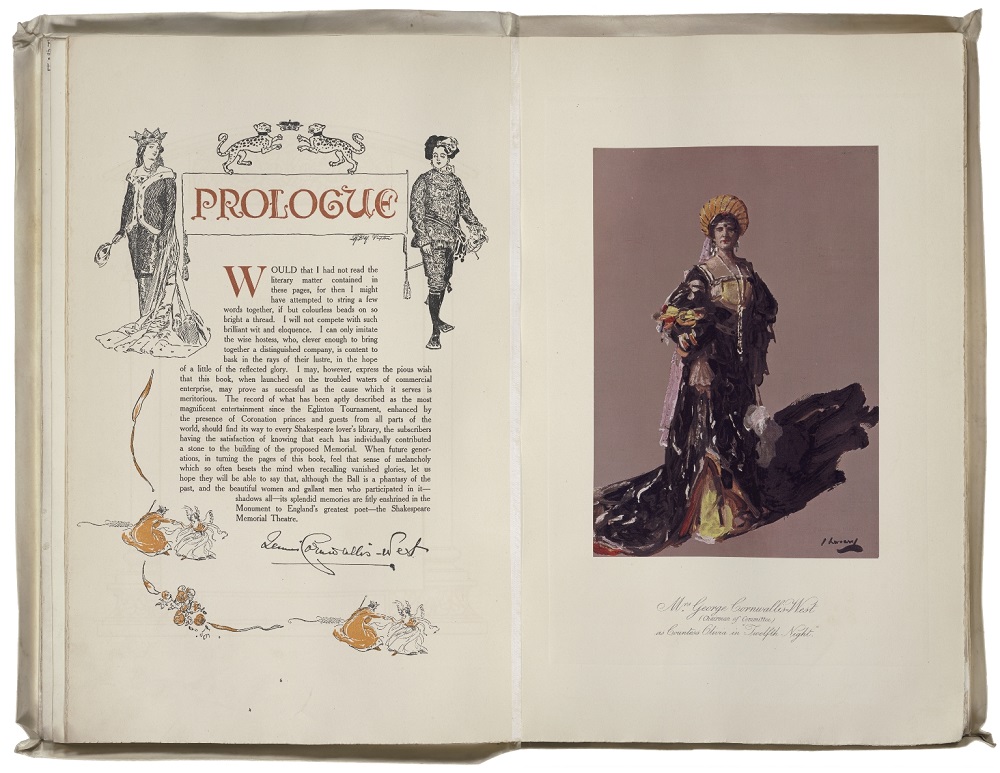

Shakespeare Memorial Souvenir of the Shakespeare Ball

Edited by Mrs. George Cornwallis-West. London; New York: F. Warne & co., 1911

Here, Churchill’s mother is shown as Countess Olivia from Twelfth Night.

(ART Vol. f231 page 6 and facing plate. Folger Shakespeare Library)

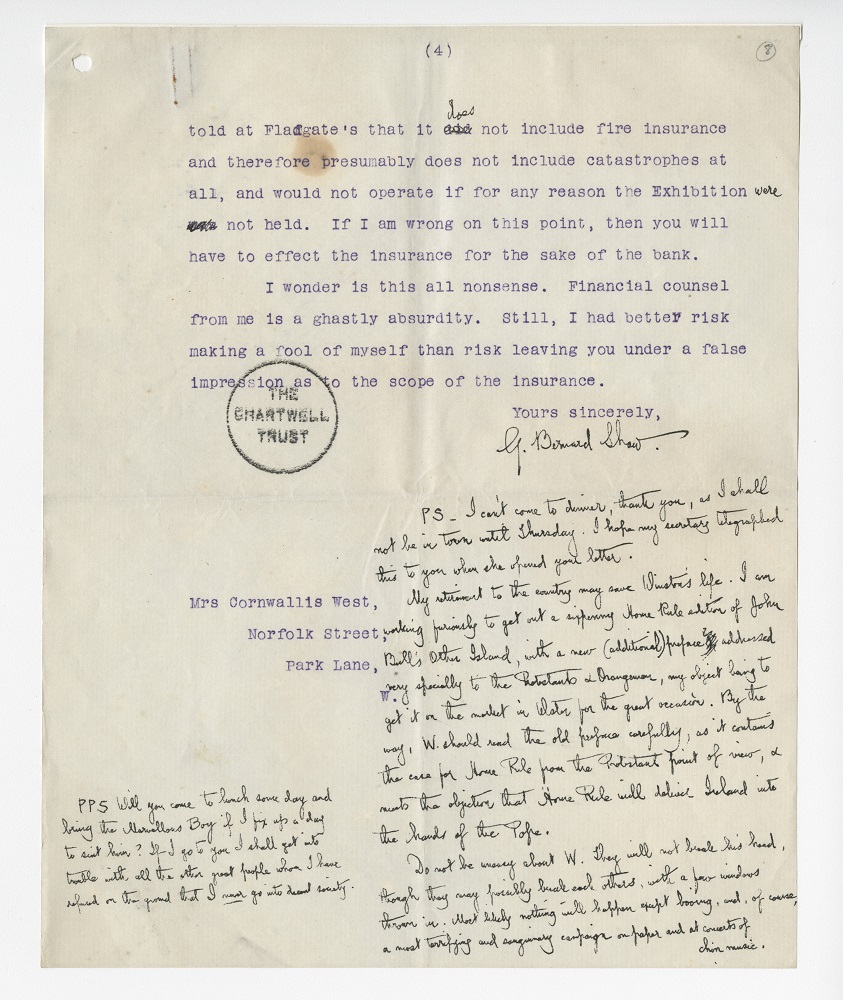

Letter from George Bernard Shaw to Mrs. Cornwallis West

January 20, 1912

In this 4-page letter, Shaw responds to a request from Lady Randolph Churchill (now Mrs. Cornwallis-West) for advice regarding insurance from Lloyd’s of London for her planned festival on Shakespeare’s England. He finally says, “Financial counsel from me is a ghastly absurdity.” In a footnote, he invites her to lunch and tells her to bring “the Marvellous Boy” (Winston).

(CHAR 28/81/8. Churchill Archives Centre. Permission given by the George Bernard Shaw Estate)

War as Melodrama

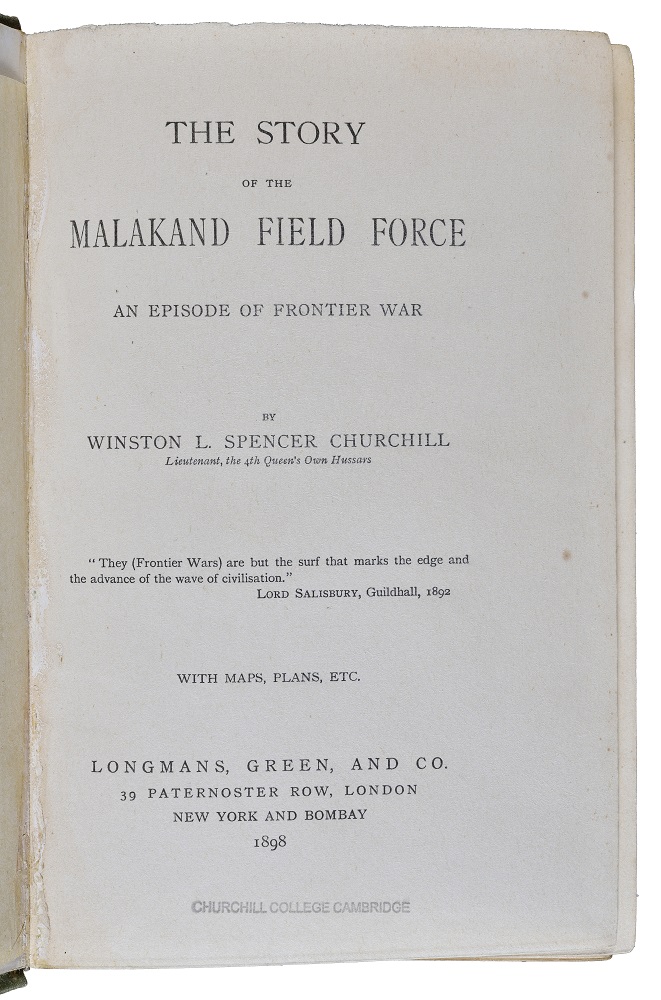

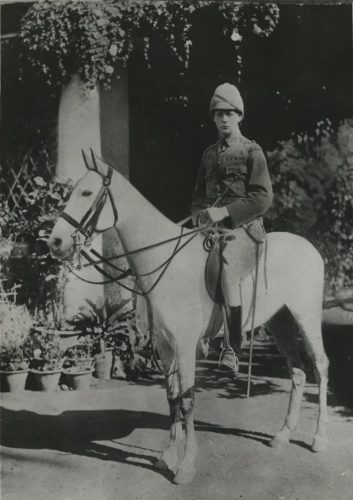

Chapter One of Churchill’s first book was called “The Theatre of War.” This account of his first warfare experiences reflected his vision of war as a theatrical performance and echoed Shakespeare’s view of the world as a stage.

In his first book, published when he was twenty-three, Churchill re-imagines his early experiences with battle as theatrical performance. The Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898) is based on his letters to the Daily Telegraph as war correspondent from the northwest frontier of the British empire in India. He saw action there after graduating from Sandhurst, the British military academy. Churchill fought as an embedded correspondent with the British and Sikhs against groups of Afghan tribesmen over contested territories in valleys along the Peshawar border.

Shakespeare provided Churchill with a framework to describe his first encounter with war. Churchill heads the Preface of The Malakand Field Force with a quotation from Shakespeare’s King John: “According to the fair play of the world,/ Let me have an audience” (ACT 5, SCENE 2, LINES 119-20). Chapter One begins with a description of the “scenery” of northwest India. Later in the book, he goes on to describe the soldiers as actors in “the great drama of frontier war … played before a vast … audience.”