Shakespeare and Churchill at War

Hamlet and World War I

In 1916, commemorating the 300th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, the New York Times ran a special supplement which included the writer’s reception among several countries engaged in the war: Britain, France, Russia, Germany, and soon, the United States. Ironically, Shakespeare was especially admired in Germany, where his work had been performed since the 17th century, and where he was known as “Unser Shakespeare” — “Our Shakespeare.” A war of words about who better understood Shakespeare broke out in English and German periodicals. Scholar Bernhard Fehr wrote: “Germany is Hamlet, not only the dreaming romantic, but the rising hero of this great age.”1 References to Hamlet were prevalent in the French and German war of words as well. Considering the postwar devastation, French poet Paul Valéry wrote, “the Hamlet of Europe now looks upon millions of ghosts … [he] hardly knows what to do with all these skulls.”2

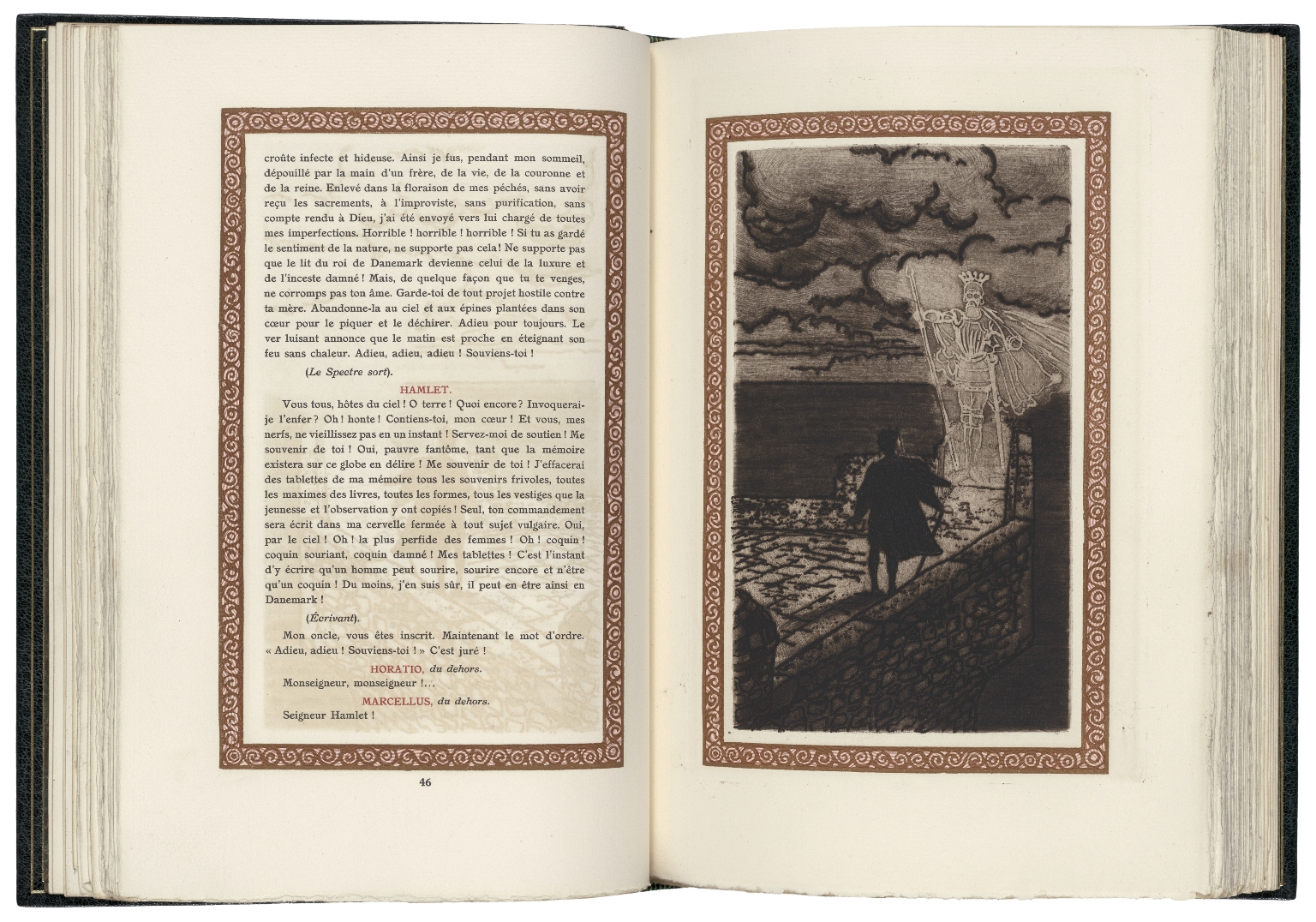

“Hamlet: drama en 5 actes” by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Translated by Georges Duval. Paris: Aug. Blaizot, 1913

This limited-edition Hamlet from 1913 contains original etchings by the French artist, Georges Bruyer (1883-1962). The following year, he began serving as a combat artist during World War I. He recorded life in the trenches and was wounded, for which he received the Croix de Guerre, a French military honor.

(PR2796 F6 H1 1913 Sh.Col. Folger Shakespeare Library)

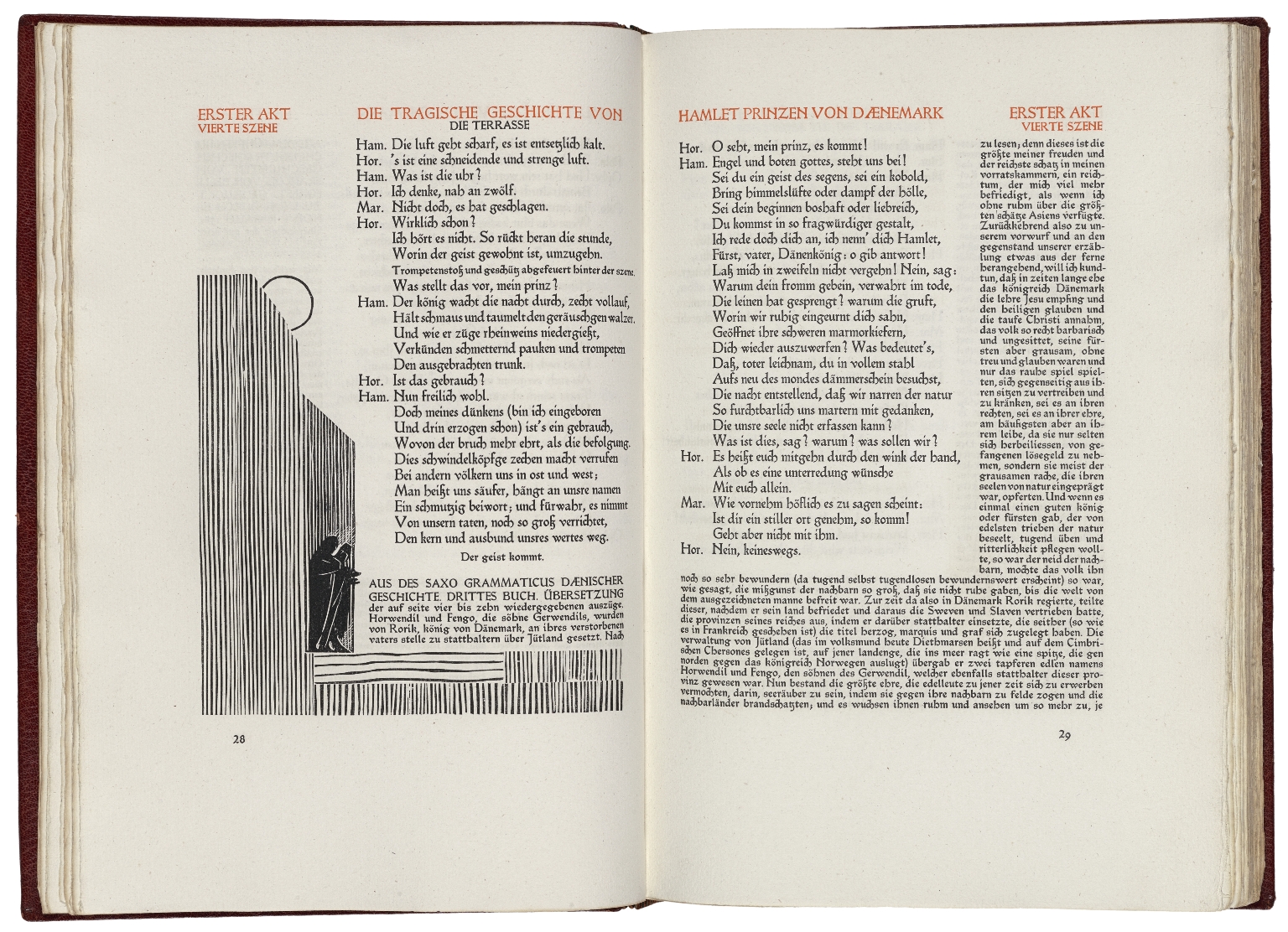

“Die Tragische Geschichte von Hamlet Prinzen” by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Translated by Gerhart Hauptmann. Weimar: Cranach Presse, 1928

Published between the First and Second World Wars, this is one of the most famous German editions of Hamlet. The woodcut illustrations by English artist Edward Gordon Craig (1872-1966) were commissioned in 1913 by German publisher Count Harry Kessler (1868-1937). Kessler met Churchill’s mother socially before serving in World War I himself on the German side.

(PR2796 G3 H1 1928 Sh.Col. Folger Shakespeare Library)

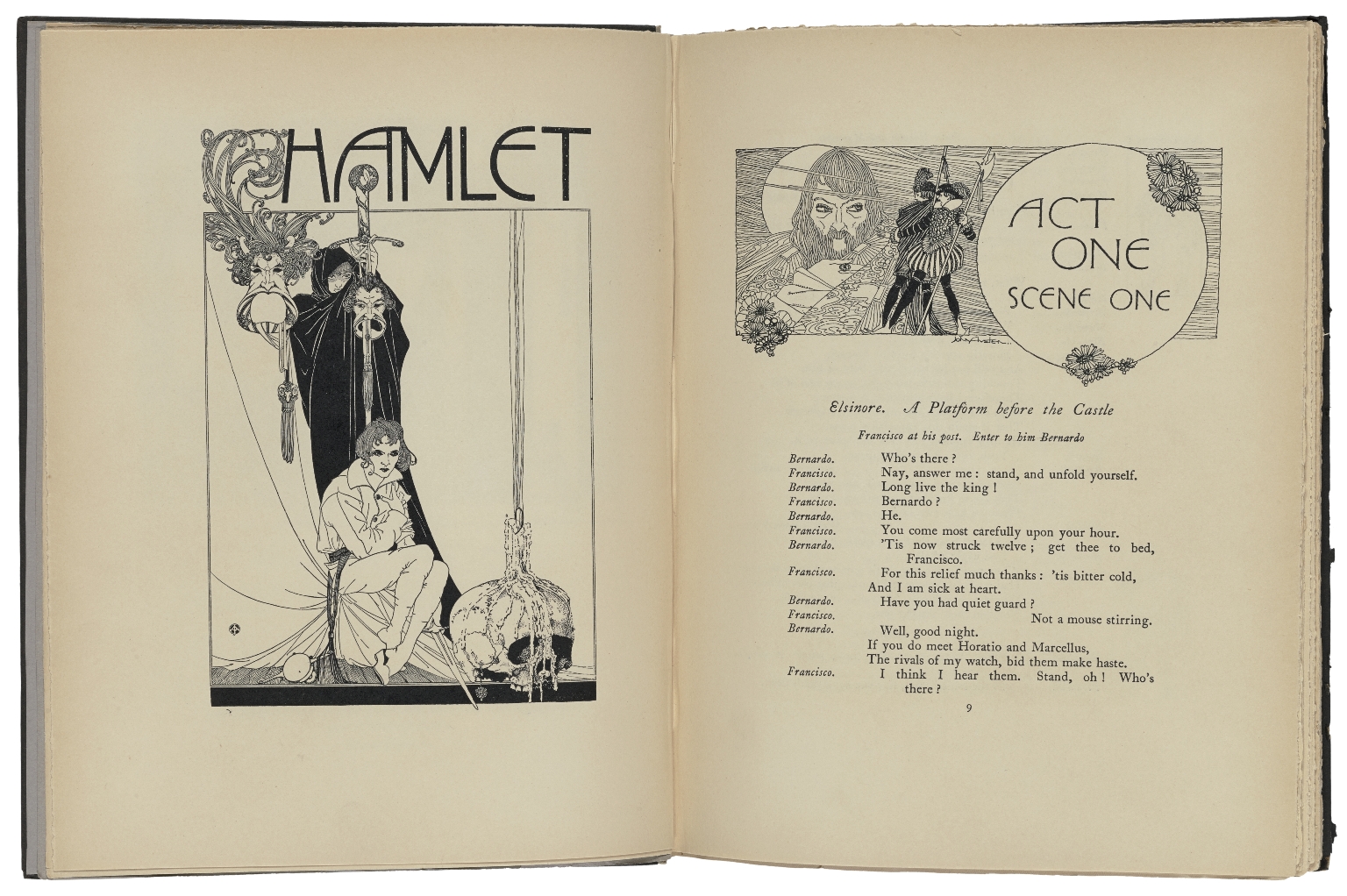

“Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Prince of Denmark” by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Decorated by John Austen. London: Selwyn & Blount, 1922

This limited edition of Hamlet was only the second published book by English illustrator John Austen (1886-1948), but it made him famous. His style shows an early influence from Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898), a leading artist of the Aesthetic Movement in late nineteenth-century Britain. The Aesthetic Movement emphasized “art for art’s sake,” or beauty and design over narrative.

(PR2807 A362 copy 1 Sh.Col. Folger Shakespeare Library)

The Cranach Hamlet

Henry V, Hamlet and World War I

Henry V and Hamlet were often invoked by the English, French and Germans during the First World War. The plays were performed by troops, read by officers before a battle, and even featured in political cartoons.

During World War I, Henry V in particular was re-imagined as a play showing the long relationship between England and France, especially as 1915 marked the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt fought by Henry V. English troops performed scenes from the play in France, highlighting the union of the two countries by the marriage of Henry with French princess Katherine. They also performed Hamlet, rousing the audience of soldiers with an appearance of Henry V at the end reciting “Once more unto the breach, dear friends.” In an odd coincidence, both the English and German presses reported that their officers read Hamlet to satirize both Churchill and American President Woodrow Wilson. And Churchill himself cites Hamlet against what he saw as delaying tactics employed by the Admiral of the Fleet in 1915.

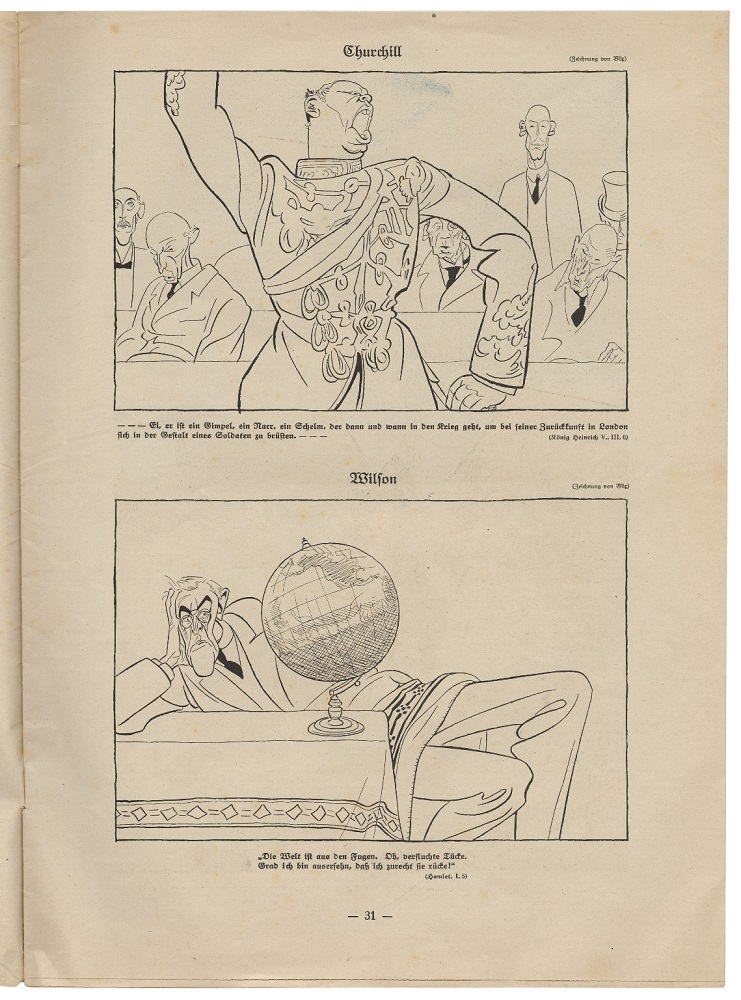

Winston Churchill as Pistol and President Woodrow Wilson as Hamlet

Cartoon from “Simplicissimus,” April 18, 1916

German cartoons disparaged both the English and the Americans during World War I. Churchill is depicted as Pistol in Henry V with the caption: “Why, ’tis a gull, a fool, a rogue, that now and then goes to the wars to grace himself at his return into London under the form of a soldier” (Henry V, Act 3, scene 6, lines 66-68). Wilson is shown as Hamlet, saying: “The time is out of joint: O, cursed spite/ That ever I was born to set it right!” (Hamlet, Act 1, scene 5, lines 210-211).

(Sh.Misc. 2321. Folger Shakespeare Library)

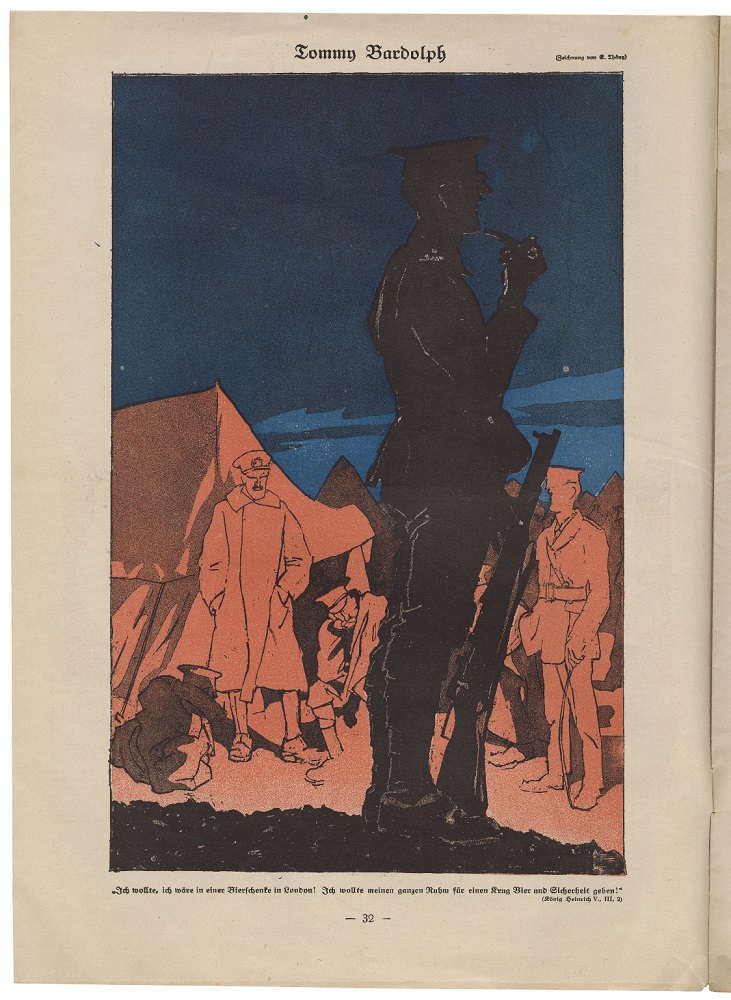

“Tommy Bardolph”

from “Simplicissimus,” April 18, 1916

This cartoon references English soldiers, known as “Tommies,” and Bardolph from Henry V.

(Sh.Misc. 2321. Folger Shakespeare Library)

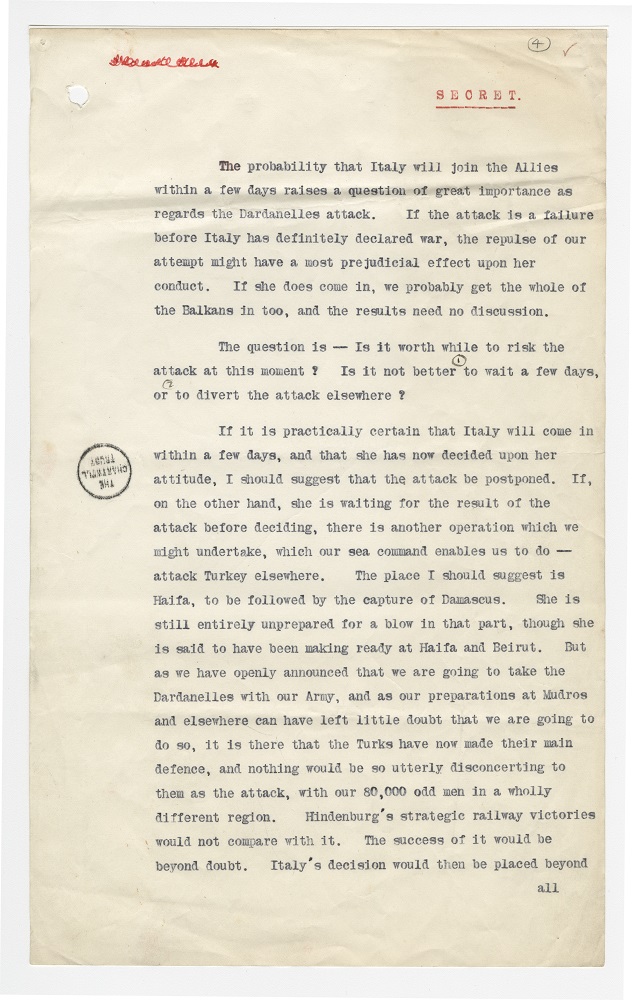

Memorandum from Lord Fisher to Winston Churchill

April 8, 1915

This memorandum, marked “Secret” by Admiral of the Fleet Lord Fisher during World War I, deals with plans to attack the Dardanelles. Fisher advises delaying until the Italians have joined the Allies (at that point Britain, France and Russia): “If she [Italy] does come in, we probably get the whole of the Balkans in too and the results need no discussion. The question is—is it worth while to risk the attack at this moment?”

(CHAR 13/57/4. Churchill Archives Centre)

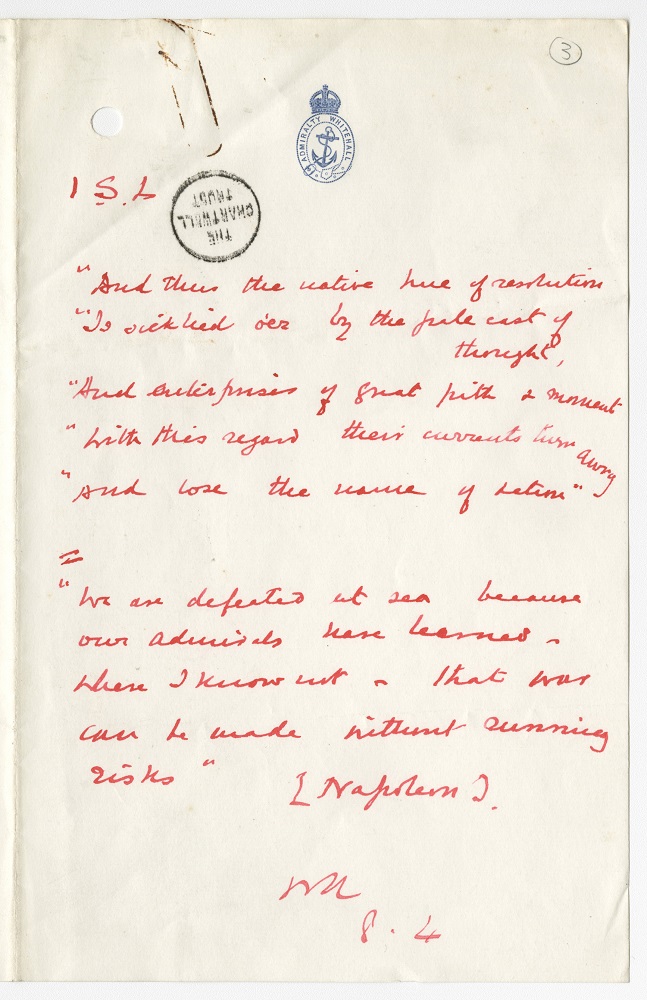

Minute from Winston Churchill to Lord Fisher

April 8, 1915

Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, responds to Fisher with a quotation from Hamlet opposing delay and caution. “And thus the native hue of resolution/ Is sicklied o’er by the pale cast of thought./ And enterprises of great pith & moment/ . . . lose the name of action.” (Hamlet Act 3, scene 1, lines 92-96)

(CHAR 13/57/3. Churchill Archives Centre)

Winston Churchill giving a speech

c. 1910-1915

(CSCT 05/003/116. Churchill Archives Centre)

Actors in a Grand Global Drama – World War II

The notion of the world as a stage is older than Shakespeare, but he immortalized the thought in this famous speech given by Jacques in As You Like It. Churchill’s speeches in World War II often echo the theme of one person having many parts to play.

During the darkest days of 1941, when the Royal Air Force was heavily attacking German cities but losing many pilots, Churchill spoke to students at Harrow. He asked to change a line in the school song from “Nor less we praise in darker days,” to “sterner days.” “These are not dark days,” he said, “these are great days,” and we should be thankful “that we have been allowed, each of us according to our stations, to play a part.” Again, in December of 1941, Churchill echoed the idea of everyone playing a part in the war effort in a speech to the Canadian Parliament: “The mine, the factory, the dockyard … the chair of the scientist, the pulpit of the preacher – from the highest to the humblest tasks, all are of equal honour; all have their part to play.”

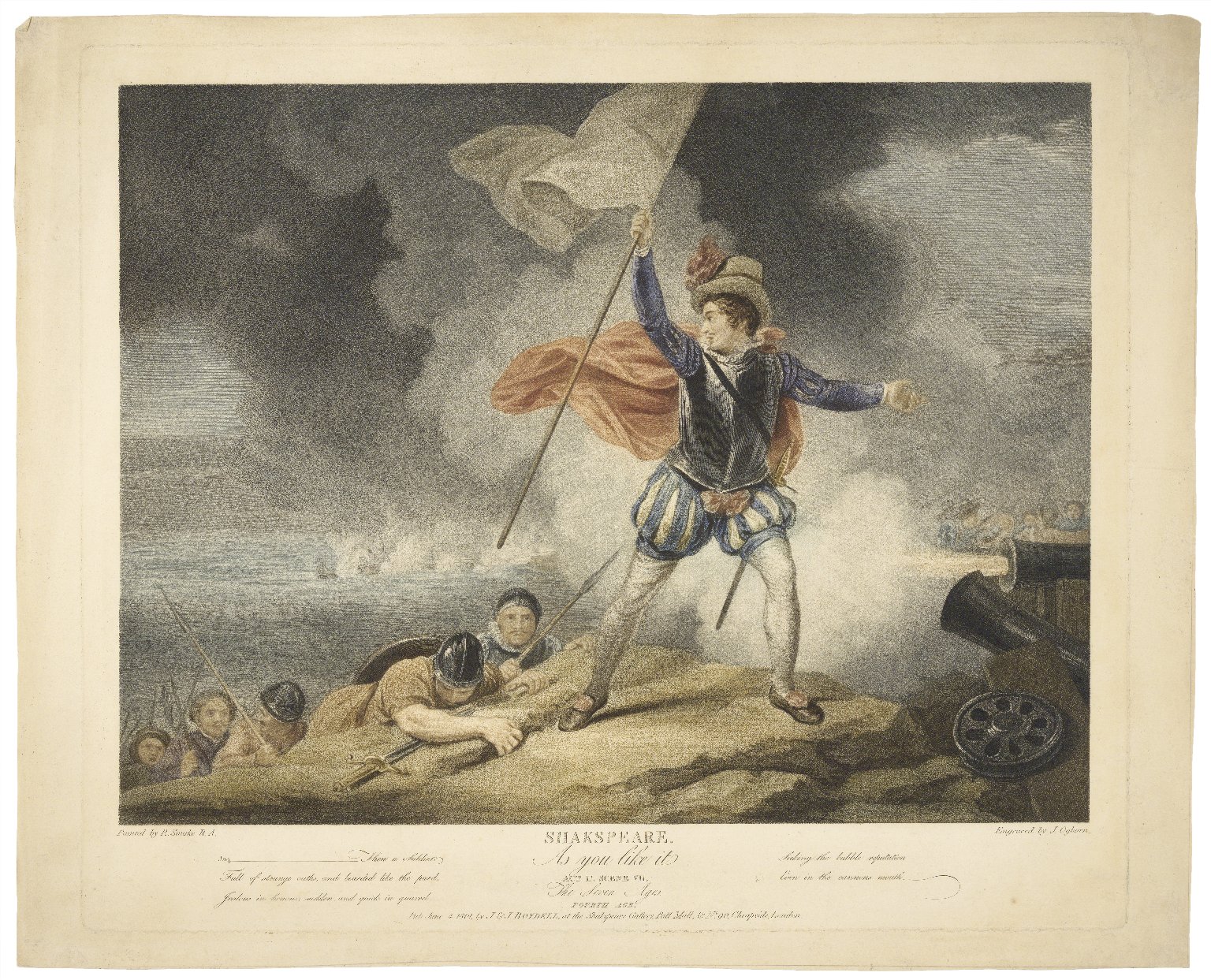

“And all the men and women merely players”

“Soldier” from “The Seven Ages of Man” by P.W. Tomkins after Robert Smirke. Boydell Shakespeare Gallery: London, 1801

This painting illustrates one of the Seven Ages of Man in As You Like It.

(ART File S528a4 no. 145 part 4 copy 1. Folger Shakespeare Library)

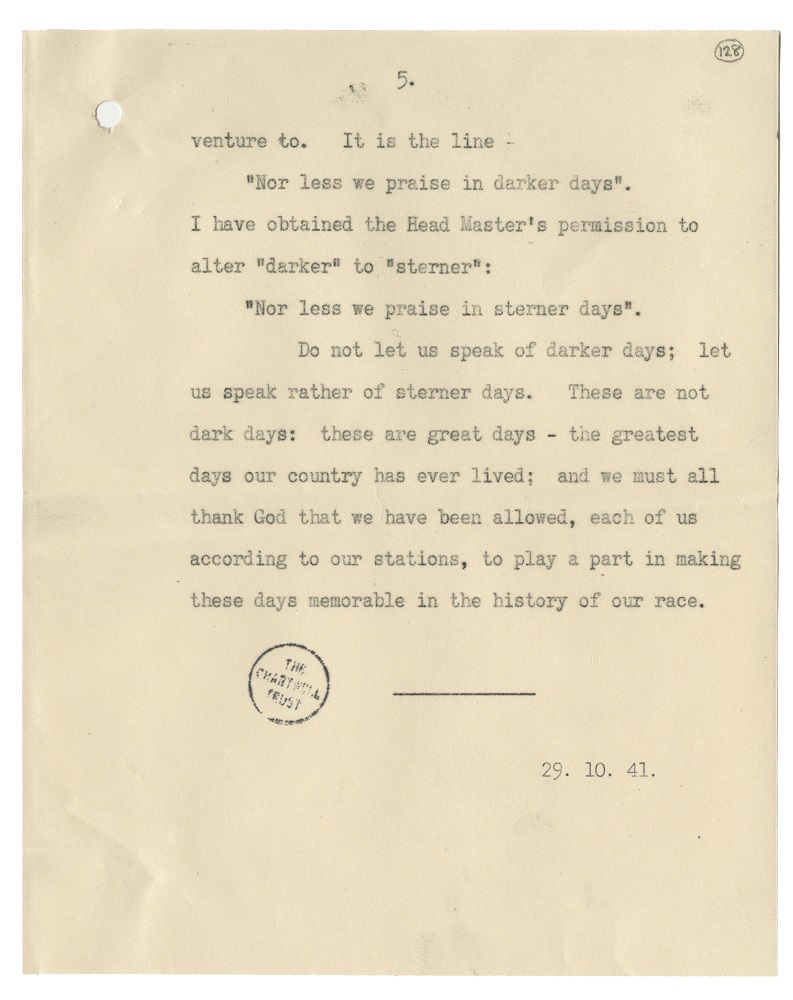

“Nor less we praise in sterner days”

In the last page of Winston Churchill’s speech at Harrow School on October 29, 1941, he refers to the Seven Ages of Man speech in As You Like It.

(CHAR 9/152B/128. Churchill Archives Centre © The Estate of Winston S. Churchill)

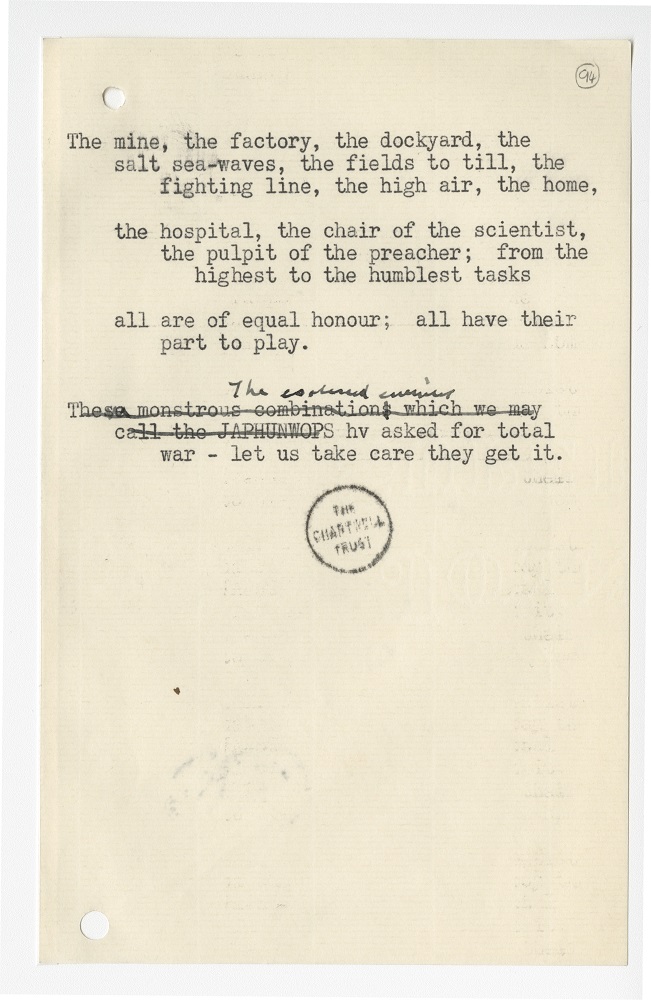

“All have their part to play”

In the last page of Winston Churchill’s speech to the Canadian Parliament on December 30, 1941, he returns to the idea that everyone has their own part to play in the war effort.

(CHAR 9/153/94. Churchill Archives Centre © The Estate of Winston S. Churchill)

“Their Finest Hour:” Churchill’s Speeches

Henry V and World War II

At the height of the Battle of Britain in August 1940, Churchill pronounced some of his most famous speeches of the war. His moving and defiant words were reminiscent of the speech by Shakespeare’s Henry V before the Battle of Agincourt.

Churchill was very moved during a visit to the operations room at Uxbridge, which was tracking the course of the Battle of Britain. He said to General Ismay, “Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few.” A few days later he used the phrase in a speech to the House of Commons, making it one of his most famous speeches of the war.

Another famous speech occurred two months earlier, after the rescue of British forces from Dunkirk. Churchill rallied the nation with defiant words worthy of Henry V before the Battle of Agincourt on St. Crispin’s day. Henry said, “And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by, / From this day to the ending of the world,/ But we in it shall be rememberèd” (Act 4, Scene 3, Lines 59-61). Churchill echoed him: “if the British Empire … lasts for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’”

“Henry the Fifth” by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Edited by G.B. Harrison. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1937

Churchill was obviously stirred by Henry V’s rousing speeches in Shakespeare’s play. On St. Crispin’s Day before the Battle of Agincourt, Henry encouraged his soldiers by promising that everyone who remembers this day will think of them, “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.” (Henry V, Act 4, scene 3, line 62)

(PR2753 H4 1937 Sh.Col. vol 11. Folger Shakespeare Library)

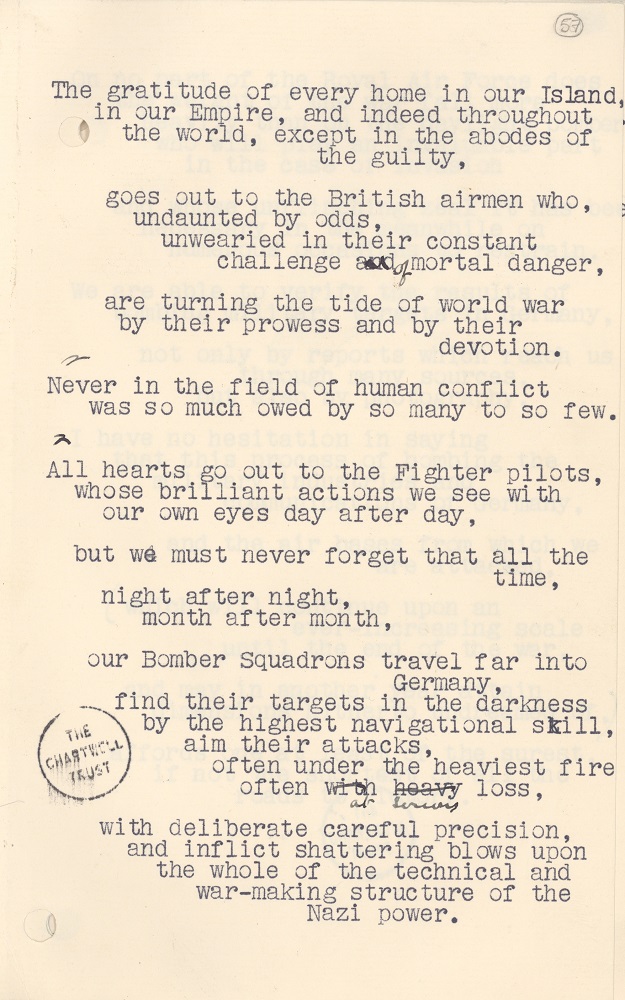

Winston Churchill’s speech “The Few”

August 20, 1940

Churchill’s famous speech in the House of Commons in August 1940 praises British pilots, and says in words that echo Henry V, “Never in the field of human conflict/ was so much owed by so many to so few.”

(CHAR 9/141A/57. Churchill Archives Centre © The Estate of Winston S. Churchill)

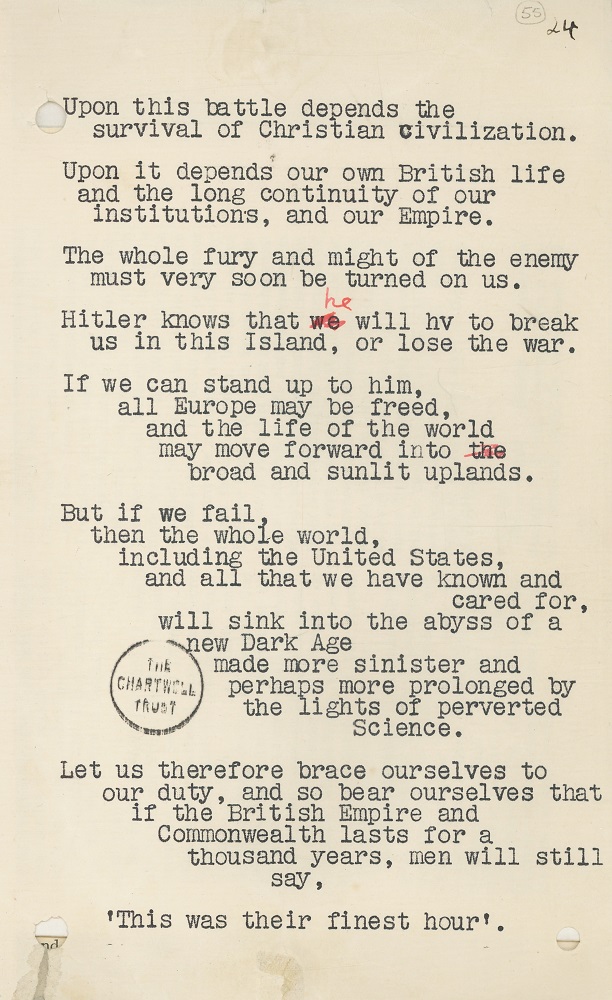

Winston Churchill’s speech “Their Finest Hour”

June 18, 1940

Two months earlier, after Dunkirk, Churchill rallied the country with this defiant speech in the tone of Henry V: “Let us therefore brace ourselves to/ our duty, and so bear ourselves that/ if the British Empire . . . lasts for a/ thousand years, men will still say,/ ‘This was their finest hour.’”

(CHAR 9/140A/55. Churchill Archives Centre © The Estate of Winston S. Churchill)

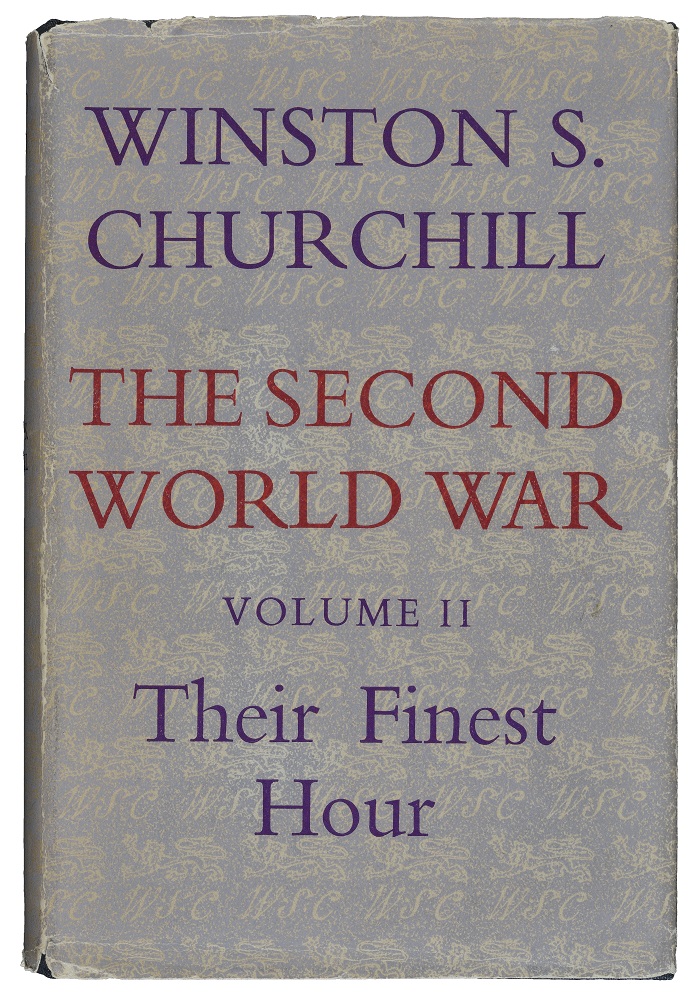

“The Second World War Vol. 2 Their finest hour”

London: Cassell, 1949

Churchill based the six volumes of his Second World War on his own notes and on documents to which he and his assistants had access. He ends Chapter XVI with references to two of his key statements: “All played their part”; and “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

(Lib 11. Churchill Archives Centre)

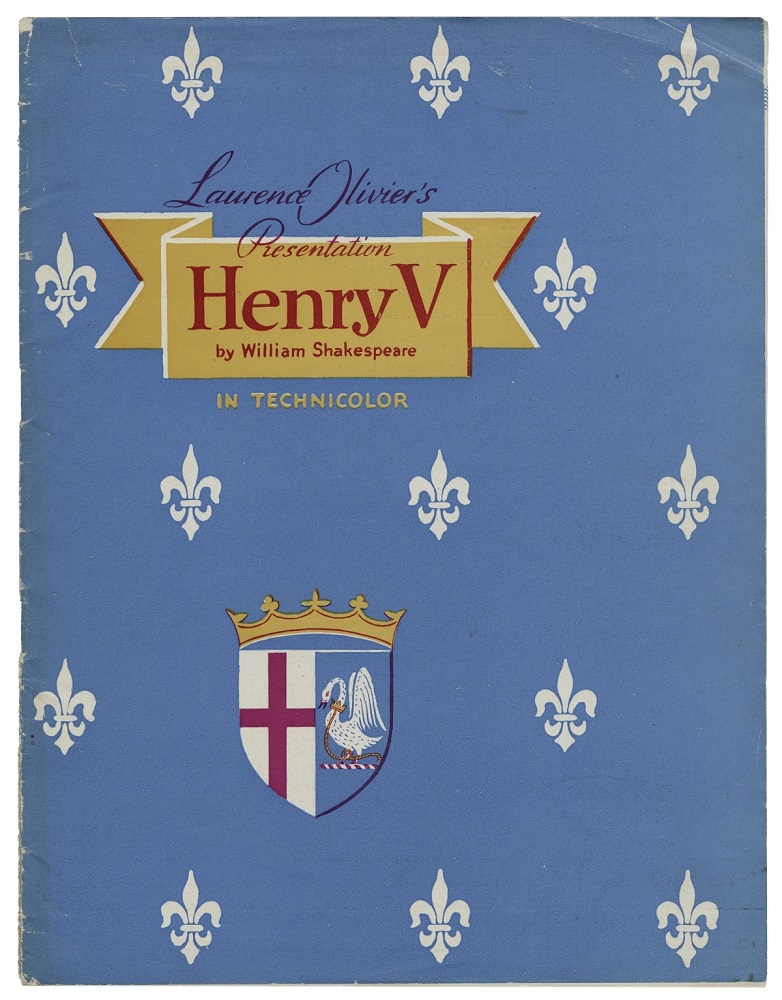

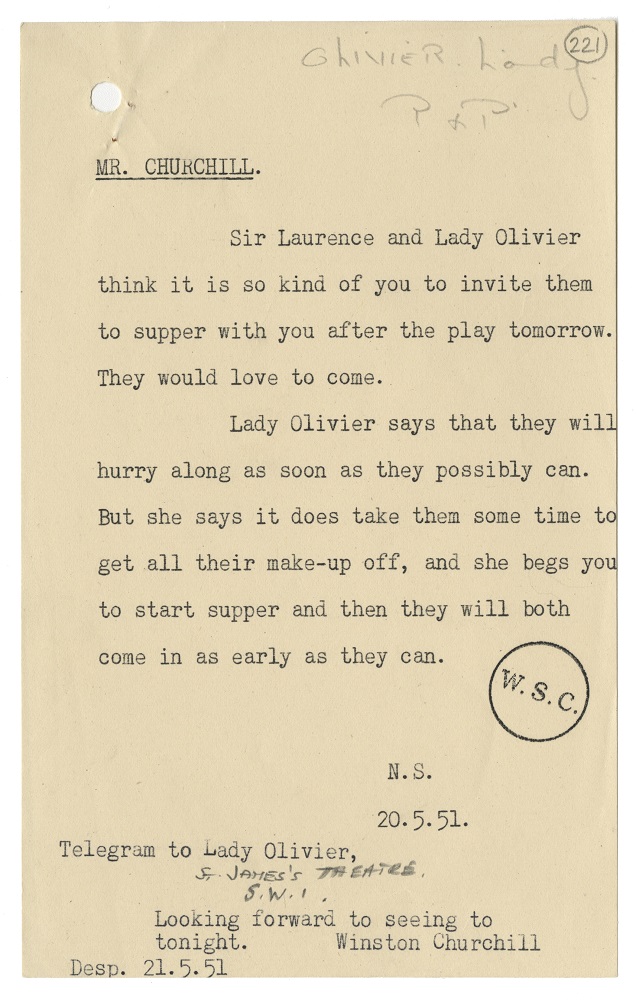

Henry V – the Propaganda Film

As World War II ground on, the British Ministry of Information called on Churchill’s friend and famous actor, Laurence Olivier, to help make films that supported the morale of the British people in those dark hours. The most well-known of these films is Henry V, which opened right after the D-Day landings in 1944. Olivier later said, “I don’t think we could have won the war without ‘Once more unto the breach …’ somewhere in our soldiers’ hearts.” The film was dedicated “To the Commandos and Airborne Troops of Great Britain,” and was admired by Churchill, who saw himself as a kind of modern Henry V, leading Britain to victory. Churchill watched the film at his official country home, Chequers, in November 1944 and “went into ecstasies about it,” according to his private secretary.