The Federal Negro Theater Unit, a subsidiary of the Works Progress Administration, was specifically designated to employ and train African Americans in theatrical production.

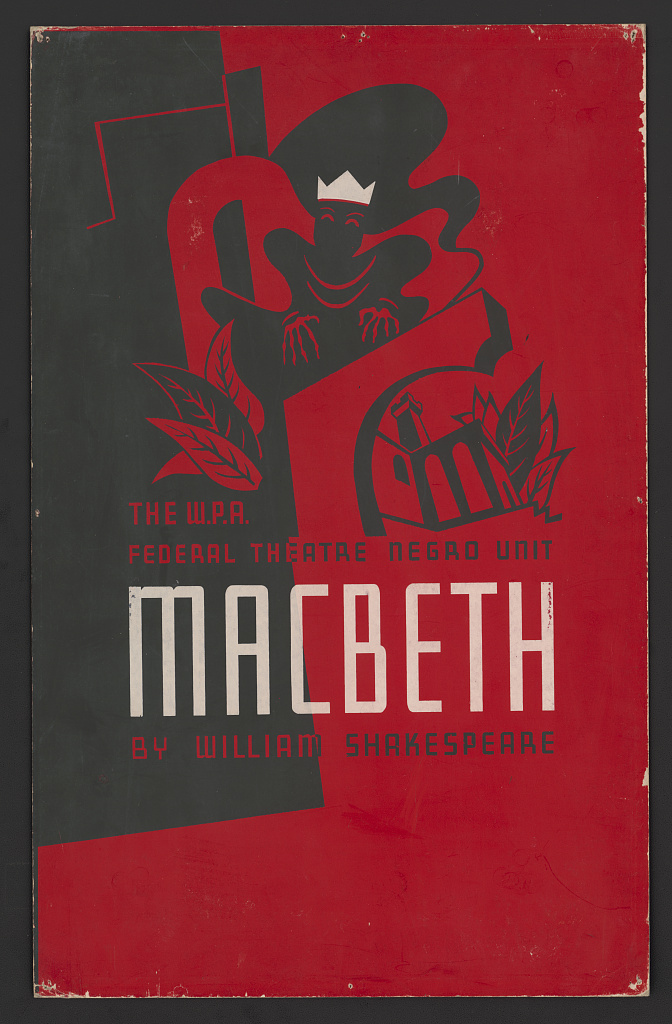

Anthony Velonis’ poster for the WPA Macbeth. Velonis, Anthony, Artist, William Shakespeare, and Sponsor Negro Theatre Project. The W.P.A. Federal Theatre Negro Unit presents Macbeth by William Shakespeare. New York: Federal Art Project, between 1936 and 1938. Photograph. https:/www.loc.gov/item/92522687/.

Anthony Velonis’ poster for the WPA Macbeth. Velonis, Anthony, Artist, William Shakespeare, and Sponsor Negro Theatre Project. The W.P.A. Federal Theatre Negro Unit presents Macbeth by William Shakespeare. New York: Federal Art Project, between 1936 and 1938. Photograph. https:/www.loc.gov/item/92522687/.During the Great Depression in the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which funded work projects that built American infrastructure and culture. These were part of federal aid projects designed to aid millions of unemployed workers. The WPA facilitated pay for services rendered, boosting the flagging morale of the American people during this time of crisis.

One of the strengths of the WPA was its approach to serving the arts community. Creative workers found themselves unable to sell art or perform for audiences because the public had no money for such luxuries. Through the WPA, visual artists, theatrical workers, musicians, and others were able to earn a living while also providing much-needed intellectual and spiritual relief to their fellow Americans.

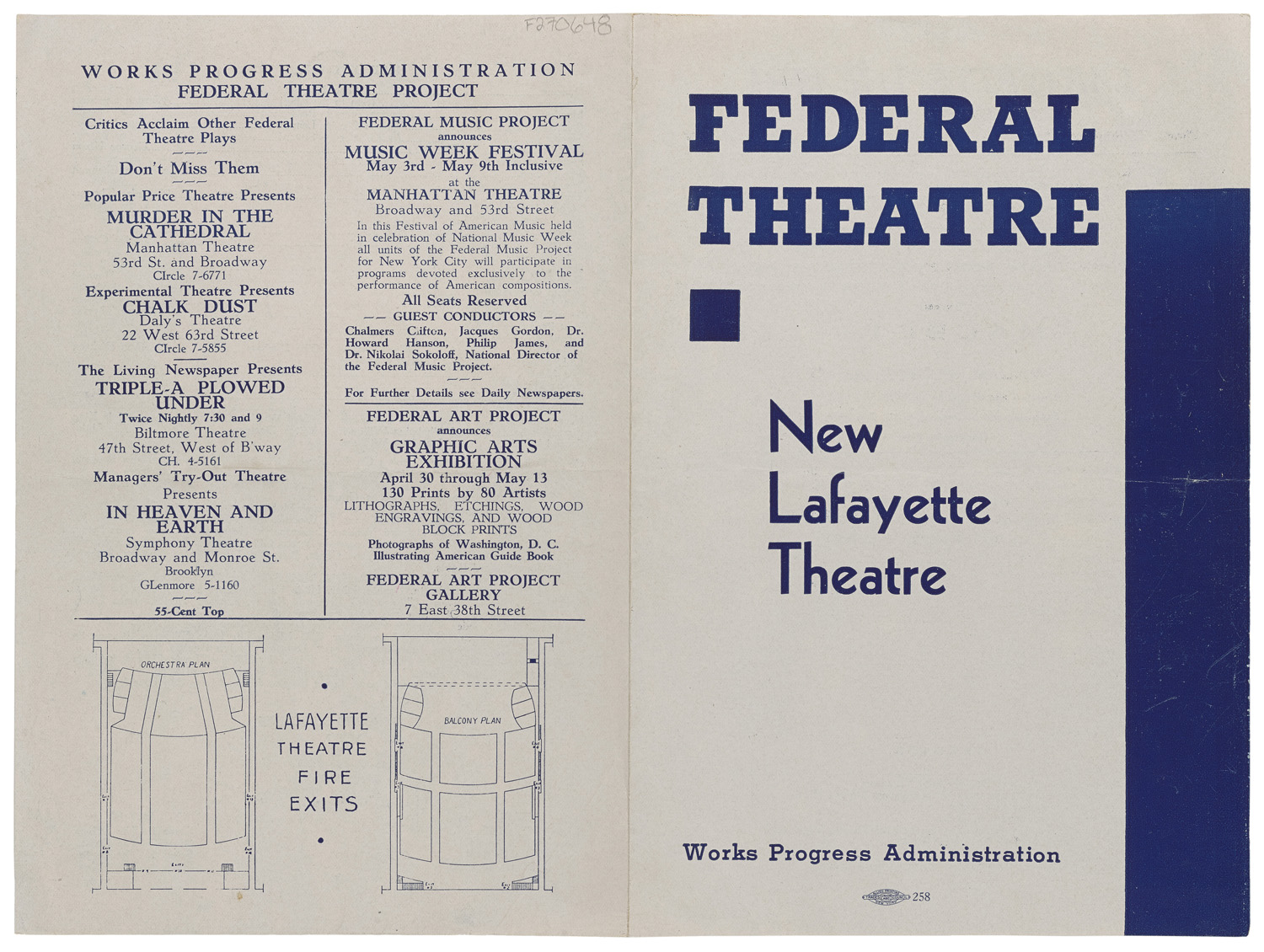

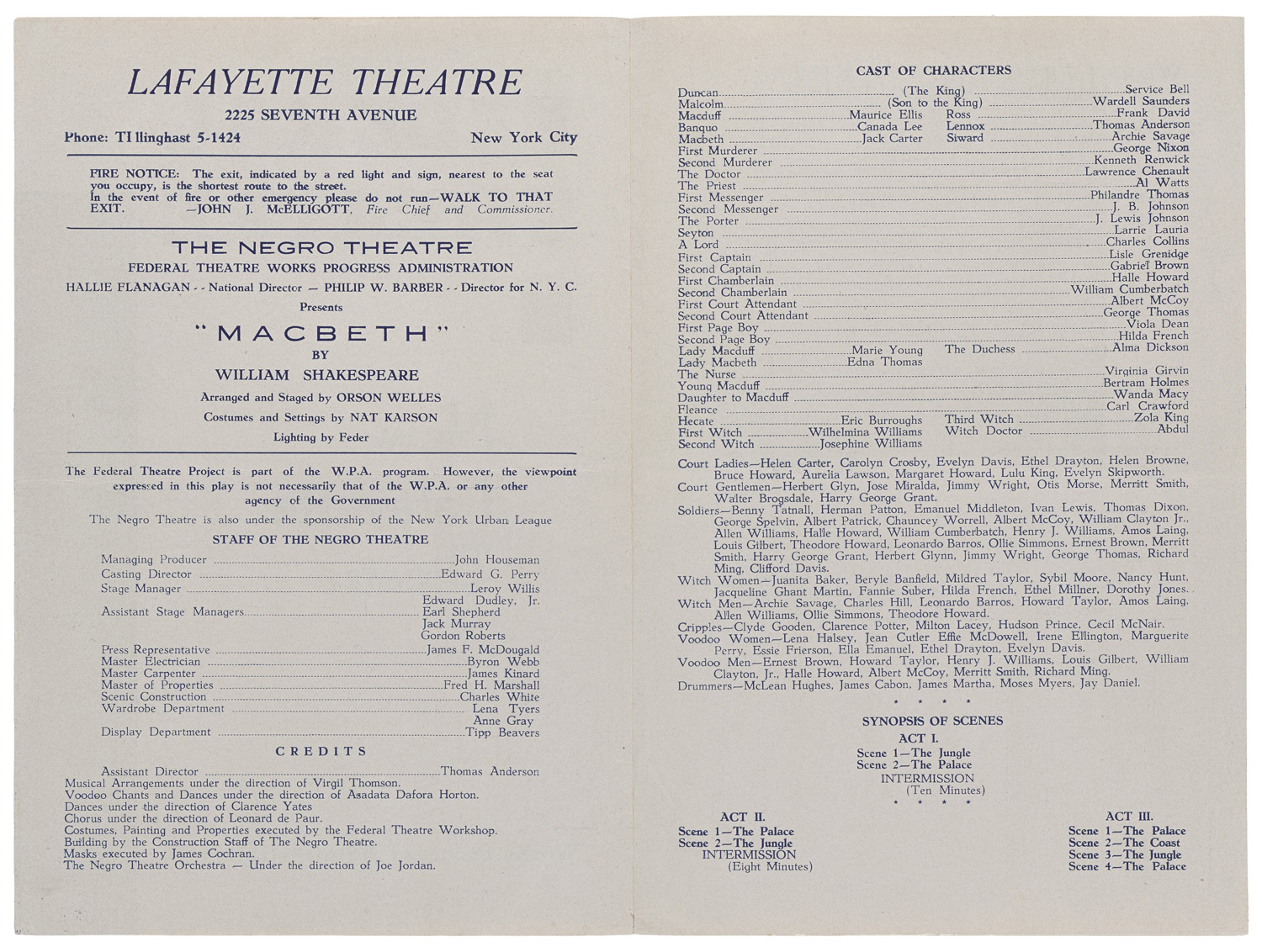

The Federal Negro Theater Unit was a subsidiary of the WPA and was specifically designated to employ and train African Americans in theatrical production. Before the creation of the unit, white stagehand unions had a monopoly on the theater production trades. Now for the first time, African Americans were encouraged to work as set-builders, lighting designers, and sound engineers, and black actors performed roles typically reserved for their white counterparts.1

Macbeth was staged in two of the earliest performances of the Federal Negro Theater Unit. The first was a traditional staging in the autumn of 1935 in Boston. The Boston run was notable for its wide variety of venues in addition to traditional theaters, including a public high school and the docks. Only a few months later, a landmark all-black production of Macbeth would demonstrate how well the WPA Theater project could simultaneously encourage creativity and employ people.

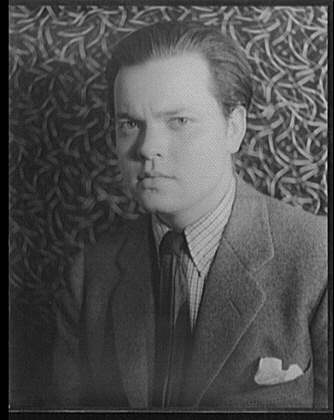

Federal Negro Theater Unit producer John Houseman brought in a precocious, yet relatively untested, twenty-year-old to adapt and direct the show — Orson Welles.

Rose McClendon (1884-1936) was the leading African-American Broadway actress of the 1920s and ’30s, and she guided the creation of the Federal Negro Theater Unit. When she became too ill to manage the New York branch of the Unit, McClendon deputized white producer John Houseman to produce Macbeth.

Orson Welles (1915-1985) had not yet brought his directorial acumen to such a prominent stage. He did have a strong familiarity with Shakespeare’s works, having acted, directed, and adapted many productions during his prolific teen years. In 1934, he collaborated on print editions of three Shakespeare plays (Twelfth Night, The Merchant of Venice, and Julius Caesar) with his former teacher Roger Hill, entitled Everybody’s Shakespeare.

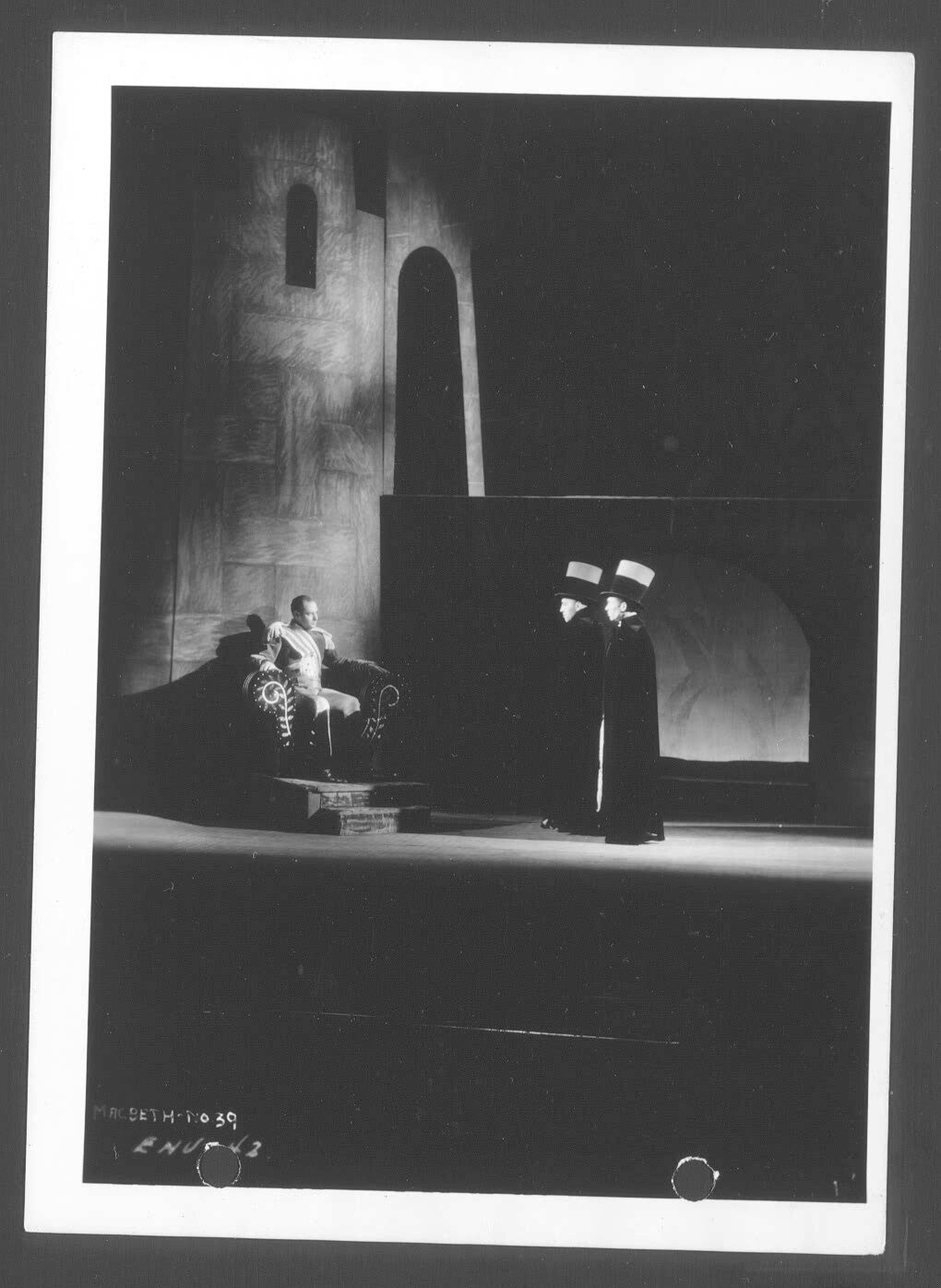

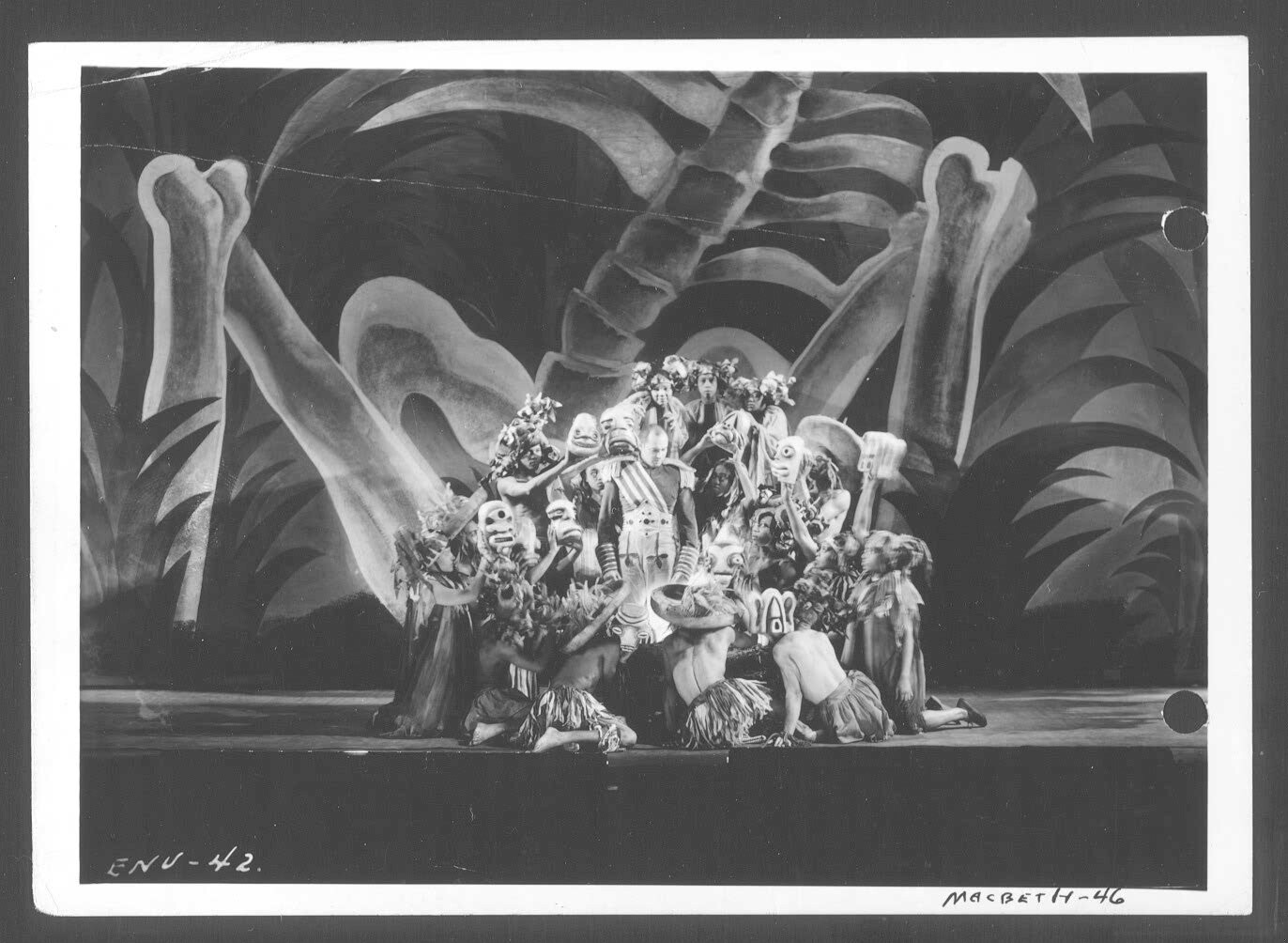

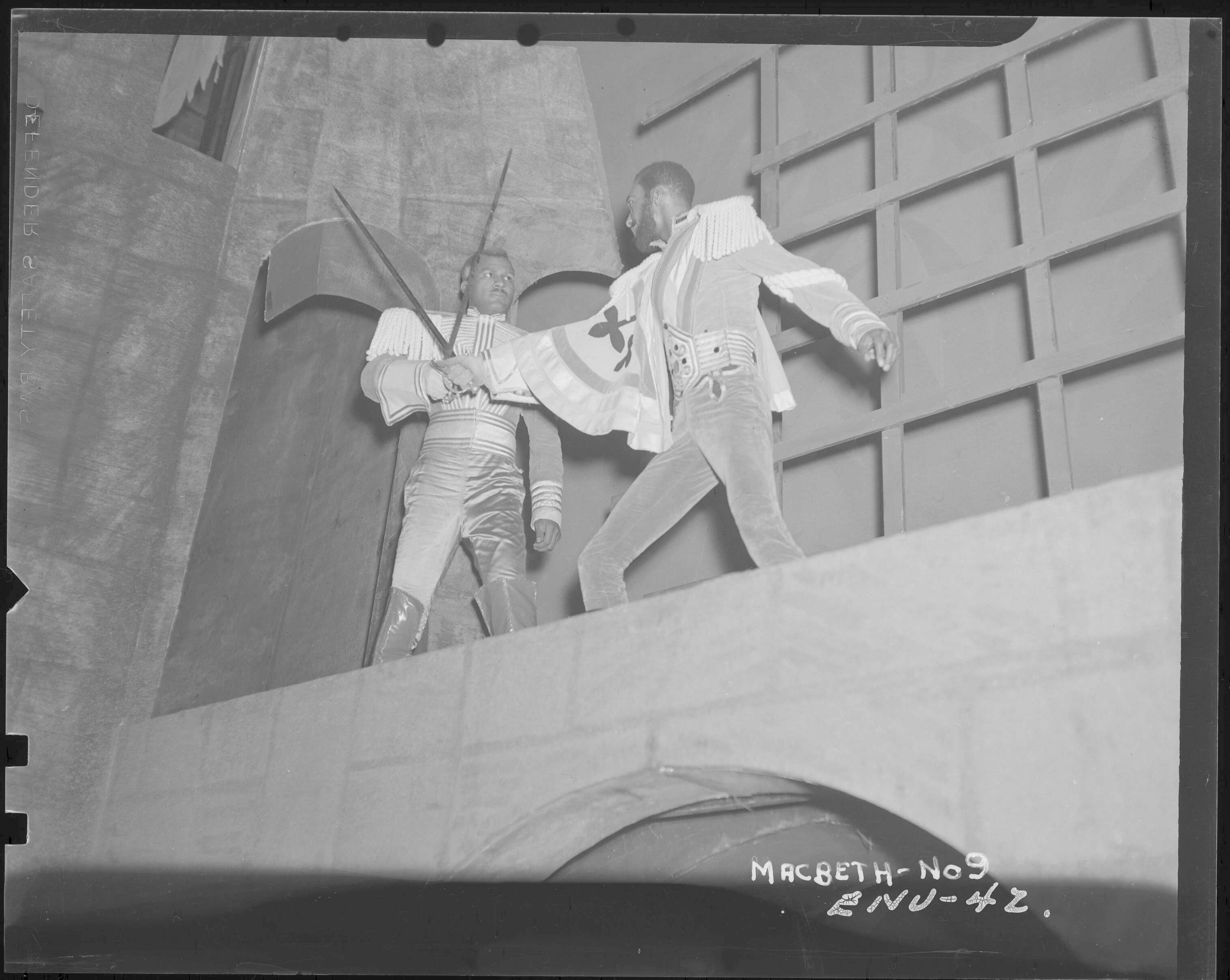

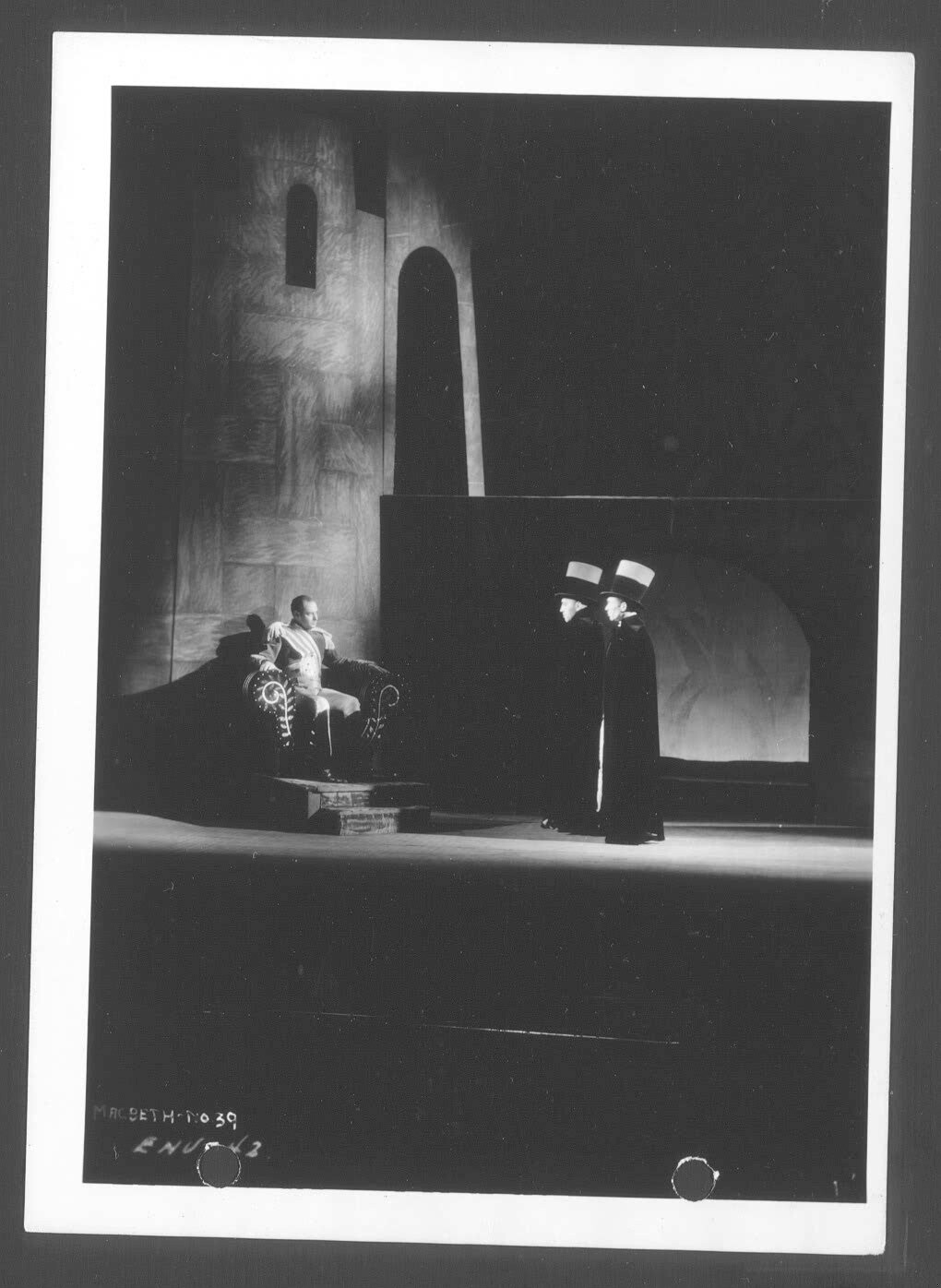

There were major differences between the 1935 Boston Macbeth and Welles’s version that opened April 14, 1936 at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem. First, Welles compressed the play into three acts. He then pulled the play out of its Scottish setting and set it in revolutionary-era Haiti. Credit for this idea is given to Orson’s first wife, Virginia Welles; yet many Americans in the 1920s and 1930s were preoccupied with the 1791-1804 revolution.2 The major painting series depicting the life of Haitian Revolution leader Touissant L’Ouverture was begun by the 21-year-old artist Jacob Lawrence in the same year as Welles’ production (Lawrence was also funded through the WPA).

Within the Haitian setting, Welles modeled the character Macbeth after Haitian dictator Henri Christophe, who ruled from 1811-1820.3 He cast Hecate (Eric Burroughs) as a witch doctor with much more agency—appearing in six of eight scenes as a “co-protagonist” with Macbeth (Maurice Ellis), even assisting in the murder of Banquo (acted by Canada Lee).4 And the three witches became voodoo priestesses, with lines greatly reduced, repeatedly chanting “the charm’s wound up.” 5

Foreshadowing his later radio successes with the Mercury Theater, Welles heavily relied on sound to accentuate the drama of the production.

He created a “tapestry of sight and sound,” punctuated with persistent drum beats by a drumming troupe from Sierra Leone.6 Adding to the stunning sets and exciting soundscape was an incredibly large troupe of players. The entire production employed 137 people in various capacities, at a wage of a little over $20 per week.7 A four-minute movie clip of the production, featured in a WPA film entitled We Work Again (1937) offers a sense of the immense number of people onstage, the setting, sound, and performance in general.

On opening night, an estimated 10,000 spectators crowded around the Lafayette Theater in Harlem. 5,000 people were admitted to the theater that night, and the curtain rose a half hour late due to the size of the crowd.8 Because so few people had disposable income, admission was subsidized with “relief nights” at five cents per ticket, allowing first-time theatergoers the chance to take a break from their cares for the evening.

The successful show went on tour to Bridgeport, Hartford, Chicago, Indianapolis, Detroit, Cleveland, and Dallas. The show played to an estimated 300,000 people total, half of whom saw the show in New York City at the Lafayette and Adelphi Theaters.9

Early theater reviews primarily praised the audiovisual experience of the play, but were reluctant to compliment the acting. Much of the criticism of the acting was obviously racist.

Early theater reviews primarily praised the audiovisual experience of the play, but were reluctant to compliment the acting. Much of the criticism of the acting was obviously racist, condemning the “imperfect articulation of Shakespeare’s language” and focusing on the bodies of the actors, rather than what they could do.10 Welles himself relied on the condescending fawning over the black actors’ pure “virgin mind,” evoking the contemporary primitivist stance when describing the actors’ ability to learn their lines and speak them well.11 In Detroit, the reviewer for the Tribune commented more favorably: “I, frankly speaking, came to condemn and remained to applaud. The show was dazzling to the eyes and pleasing to the ears. No part was over-acted, and the stage settings, the startling lighting, and the marvelous costuming combined to make as enjoyable play as I ever witnessed” (September 19, 1936).

Despite these shifting commentaries, contemporary critics view the responses to the production as much more racially problematic than the production itself, which endures as a milestone not only in African-American theater, but for the country as a whole.

PREVIOUS: Travel across Australia with the country’s first Shakespeare touring company.

NEXT: Discover the Shakespeare company bringing the Bard to new audiences across Australia.

- Sawyer, Robert, “’All’s Well that Ends Welles’: Orson Welles and the ‘Voodoo’ Macbeth,” Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation, and Performance, 13 (28), 2016, 90-91

- Rippy, Marguerite, “Black Cast Conjures White Genius: Unraveling the Mystique of Orson Welles’s ‘Voodoo’ Macbeth,” in Weyward Macbeth: Intersections of Race and Performance, eds. Scott L. Newstok and Ayanna Thompson, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, 84.

- Sawyer, Robert, “’All’s Well that Ends Welles’: Orson Welles and the ‘Voodoo’ Macbeth,” Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation, and Performance, 13 (28), 2016, 92.

- France, Richard, ed, Orson Welles on Shakespeare: the W.P.A. and Mercury Theatre Playscripts, New York, Westport, CT, and London: Greenwood Press, 1990, 33.

- France, Richard, ed, Orson Welles on Shakespeare: the W.P.A. and Mercury Theatre Playscripts, New York, Westport, CT, and London: Greenwood Press, 1990, 2.6.

- France, Richard, ed, Orson Welles on Shakespeare: the W.P.A. and Mercury Theatre Playscripts, New York, Westport, CT, and London: Greenwood Press, 1990, 32.

- Sawyer, Robert, “’All’s Well that Ends Welles’: Orson Welles and the ‘Voodoo’ Macbeth,” Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation, and Performance, 13 (28), 2016, 92.

- Sawyer, Robert, “’All’s Well that Ends Welles’: Orson Welles and the ‘Voodoo’ Macbeth,” Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation, and Performance, 13 (28), 2016, 93.

- Sawyer, Robert, “’All’s Well that Ends Welles’: Orson Welles and the ‘Voodoo’ Macbeth,” Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation, and Performance, 13 (28), 2016, 97-98.

- Rippy, Marguerite, “Black Cast Conjures White Genius: Unraveling the Mystique of Orson Welles’s ‘Voodoo’ Macbeth,” in Weyward Macbeth: Intersections of Race and Performance, eds. Scott L. Newstok and Ayanna Thompson, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, 88.

- Rippy, Marguerite, “Black Cast Conjures White Genius: Unraveling the Mystique of Orson Welles’s ‘Voodoo’ Macbeth,” in Weyward Macbeth: Intersections of Race and Performance, eds. Scott L. Newstok and Ayanna Thompson, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, 88.