A snapshot of the evolving demographic, social, and economic changes in the 1860s, this performance demonstrated the lived experience of the German immigrants in the United States, striving to navigate everything new…

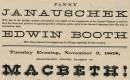

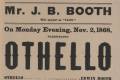

The rainy evening of November 3, 1868 marked the end of the Presidential election contest between Ulysses S. Grant and Horatio Seymour. Grant emerged victorious as the first elected president after the end of the Civil War and abolition of slavery. On that night, Edwin Booth and Fanny Janauschek performed to a crowd of nearly 3,000 people in an historic bilingual production of Macbeth in the Boston Theatre.

With only one day’s notice, Booth and Janauschek teamed up to provide one of the most electrifying performances of Macbeth on the American stage. Booth performed the part of Macbeth in English with Janauschek as Lady Macbeth, speaking in German. The result was exhilarating.

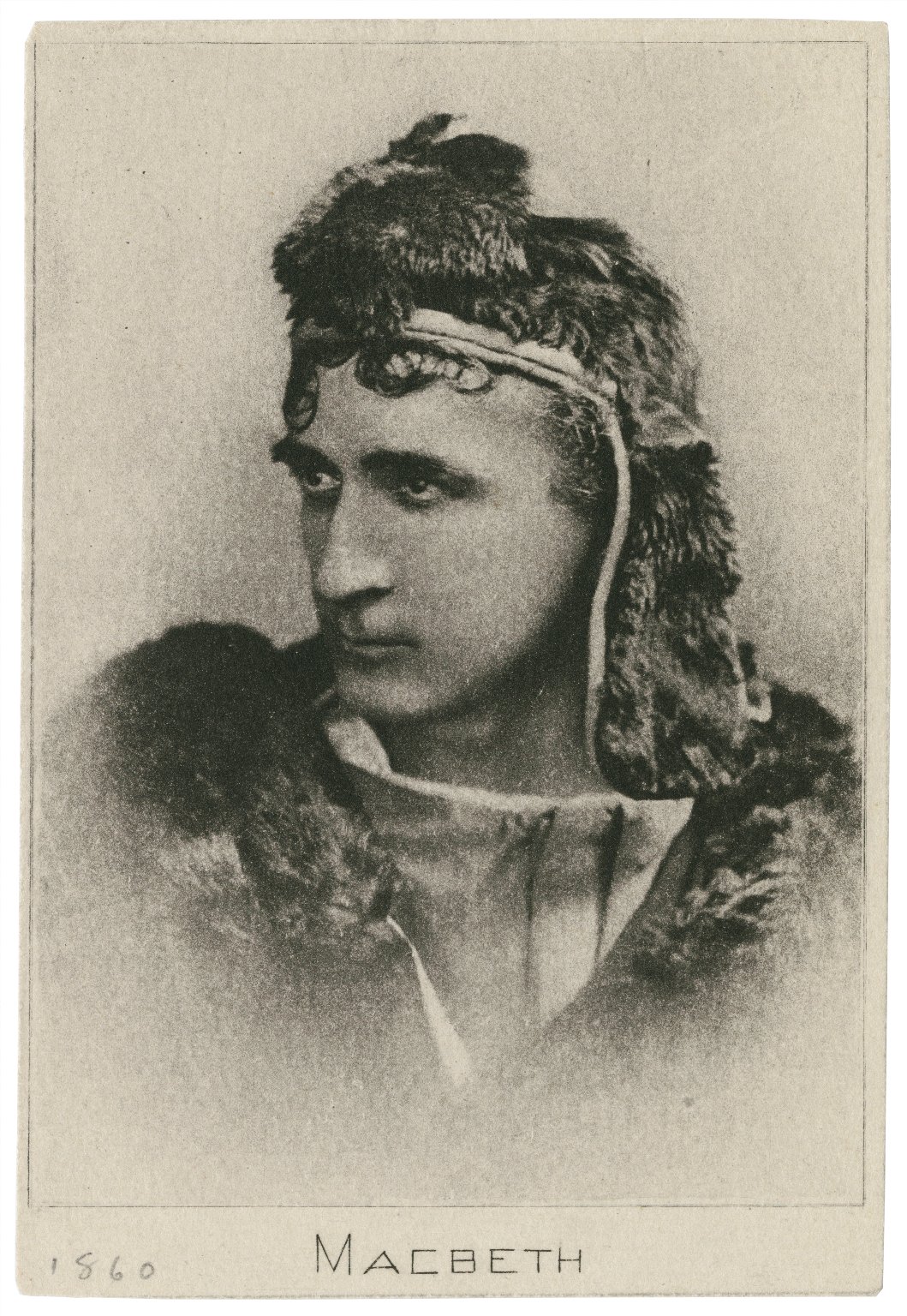

Depiction of Edwin Booth as Macbeth from ca. 1860. Folger ART File B725.4 no.34 PHOTO.

Edwin Booth (1833-1893) was the best-known and best-loved actor of his age in the United States. He learned his craft from his father, Junius Brutus Booth, who emigrated to the United States from the United Kingdom and spent his career traveling his adopted country performing Shakespeare. The elder Booth raised his three sons in the acting tradition—Junius Brutus Jr. (known as June), Edwin, and John Wilkes, who became notorious in 1865 for the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

The Booths performed both as a family and individually, with Edwin clearly emerging as the strongest talent. He became known as a tragedian, especially for his signature role of Hamlet. His career was deeply affected by his brother John Wilkes Booth’s assassination of President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865 during a Washington, D.C. performance of Our American Cousin. Soon after the assassination, Edwin announced his retirement from the stage. He returned, however, six months later in a New York production of Our American Cousin – a bold move that did not diminish his fame.

Fanny Janauschek, around the time of her appearance in the 1868 Macbeth. Folger ART File J33 no.4 PHOTO.

At the time of the performance, Booth’s partner Fanny Janauschek (1829-1904) was trying to find her place in the American theatrical network. She was a German-speaking, Czech-born ingenue, who would perform in German with an English supporting cast for several years after her 1868 performance in Macbeth.

Over time, she eventually came to rival the tragedienne Adelaide Ristori (1822-1906) in fame and accomplishments, including running her own theatrical company. She was acclaimed for the roles of Mary Stuart, Brunhild, and Meg Merrilies (Guy Mannering), and the Lady Macbeth of 1868.

“The occasion of two such brilliant stars appearing together was indeed a rare one. It was looked upon as an epoch in the history of the American stage…The acting that followed revealed beauties in Shakspeare almost undreamed of before…”1

On that night in 1868, Edwin Booth was making his slow return to the stage after the tragedy and ignominy of the assassination.

Booth was used to the tradition of bilingual productions, common in the densely-populated cities in the United States and among American actors touring abroad. He often performed with acclaimed actors newly arrived from the European continent, including Tommaso Salvini and Bogumil Dawison. Perhaps driven by his father’s experience building a name for himself as a migrant to the United States, Booth used his fame to help these stars shine.

On this November night, both Booth and Janauschek brought a dynamic emotion to their performances that audiences saw as a revelation. One audience member later wrote that Booth “has revealed beauties in Shakespeare that were undreamed of before. He has thrust aside old stage tricks and customs. He has shown us the folly of set speeches and pompous intonations.”2 The same viewer later wrote of Janauschek, “Booth himself remarked to us that this scene could not be surpassed, and that Janauschek was the only actress he ever saw who seemed capable of comprehending the lofty heroism, and womanly refinement combined with the unscrupulous daring and demoniacal fury and firmness of the character.”3

The actors could not understand each others’ lines…but they found a workaround, described later in Janauschek’s obituary: Janauschek would simply pinch Booth on his cue.

These two great actors, one established and one ascendant, summoned all their creative, physical, and intellectual energies to combine in a stunning performance. Along with performing this intense play, the actors could not understand the others’ lines — quite the challenge to overcome. But they found a workaround, described later in Janauschek’s obituary: Janauschek would simply pinch Booth on his cue.4

In this bilingual performance, Janauschek and Booth used the actors’ toolkit of expression, movement, and voice to convey the story and emotion of Macbeth. Rather than place primacy on Shakespeare’s language alone, they showed how an actor’s physicality could magnify the Bard’s words.

The language differences did not keep the audience from marveling at Janauschek’s Lady Macbeth, according to reviews: “Though Janauschek spoke in German, such was the power of her facile expression and the force of her artistic gesticulation, that the meaning of her utterances was almost as comprehensive as if given in English. Her acting was a great success from beginning to end.”5 G.W. Griffin struggled to take himself outside of Shakespeare’s language when discussing Booth’s performance in this production, continually calling it “indescribable.” Because Griffin could not understand the words Janauschek delivered, he focused on her delivery and unique abilities as an actor. And German communities in other parts of America triumphantly published a translation of the favorable review of the performance in newspapers as far flung as Virginia, Tennessee, and Ohio.

A snapshot of the evolving demographic, social, and economic changes in the 1860s, this performance demonstrated the lived experience of the German immigrants to the United States as they strove to navigate everything new. It marked the beginning of a new era for all those emerging from the devastation of civil war.

PREVIOUS: Go back to the home page.

NEXT: Discover the celebrity partnership that lit up the London stage in the late 1800s.

- Griffin, G.W., Studies in Literature, Baltimore: Henry C. Turnbull, Jr., 1870, 147.

- Griffin, G.W., Studies in Literature, Baltimore: Henry C. Turnbull, Jr., 1870, 59.

- Griffin, G.W., Studies in Literature, Baltimore: Henry C. Turnbull, Jr., 1870, 150.

- New-York tribune. (New York [N.Y.]), 30 Nov. 1904. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1904-11-30/ed-1/seq-16/>

- The daily dispatch. (Richmond [Va.]), 11 Nov. 1868. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024738/1868-11-11/ed-1/seq-3/>