The curtains rose to reveal a stage immersed in darkness, thunder, and rain. A sudden flash of lightning revealed the Weird Sisters silhouetted against the sky; flying through the air, they finally landed on a “rocky eminence…”

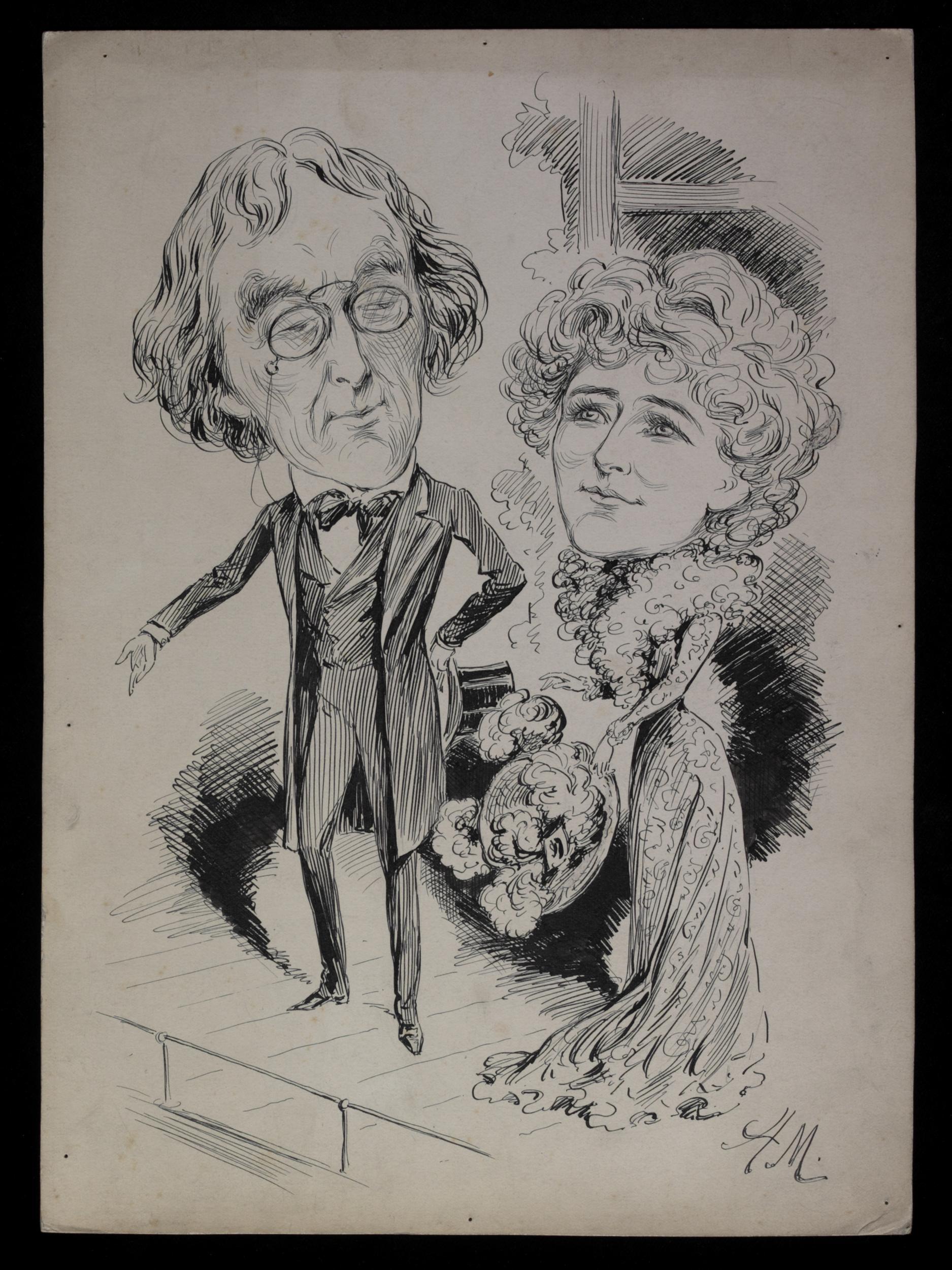

Caricature of Henry Irving and Ellen Terry, by H.M. ca. 1900. ©Victoria & Albert Museum, Harry R. Beard Collection, S.408-2010.

The Lyceum was among the most famous theaters in nineteenth-century Britain. Located on Wellington Street, close to the Strand and the heart of London’s Theatre District, it ran under the management of the actor Henry Irving (1838-1905) from 1878-1905.

Irving established the Lyceum Company in 1878, inviting the popular actress Ellen Terry (1847-1928) to become his leading lady. Together the pair became international celebrities, on tour and at home on Wellington Street.

The Lyceum became renowned for presenting spectacular productions, in which the sets were so beautiful they resembled “living paintings.”1 The costumes worn by performers were equally lavish and Irving exploited the latest technologically to create dazzling special effects. His production of Faust in 1885, for instance, included a duel in which electric sparks shot between the swords.

Macbeth in 1888 was staged a decade into Irving and Terry’s twenty-four-year partnership. Their decision to stage Macbeth was controversial, even with established reputations as Shakespearean actors through productions such as Hamlet (1878), The Merchant of Venice (1879); Othello (1881); Romeo and Juliet (1882); Much Ado About Nothing (1882) and Twelfth Night (1884).

“My mental division of the years at the Lyceum is before ‘Macbeth,’ and after. I divide it up like this, perhaps, because ‘Macbeth’ was the most important of all our productions, if I judge it by the amount of preparation and thought that it cost us and by the discussion which it provoked.”

— Ellen Terry, The Story of My Life, 1908, pg. 174

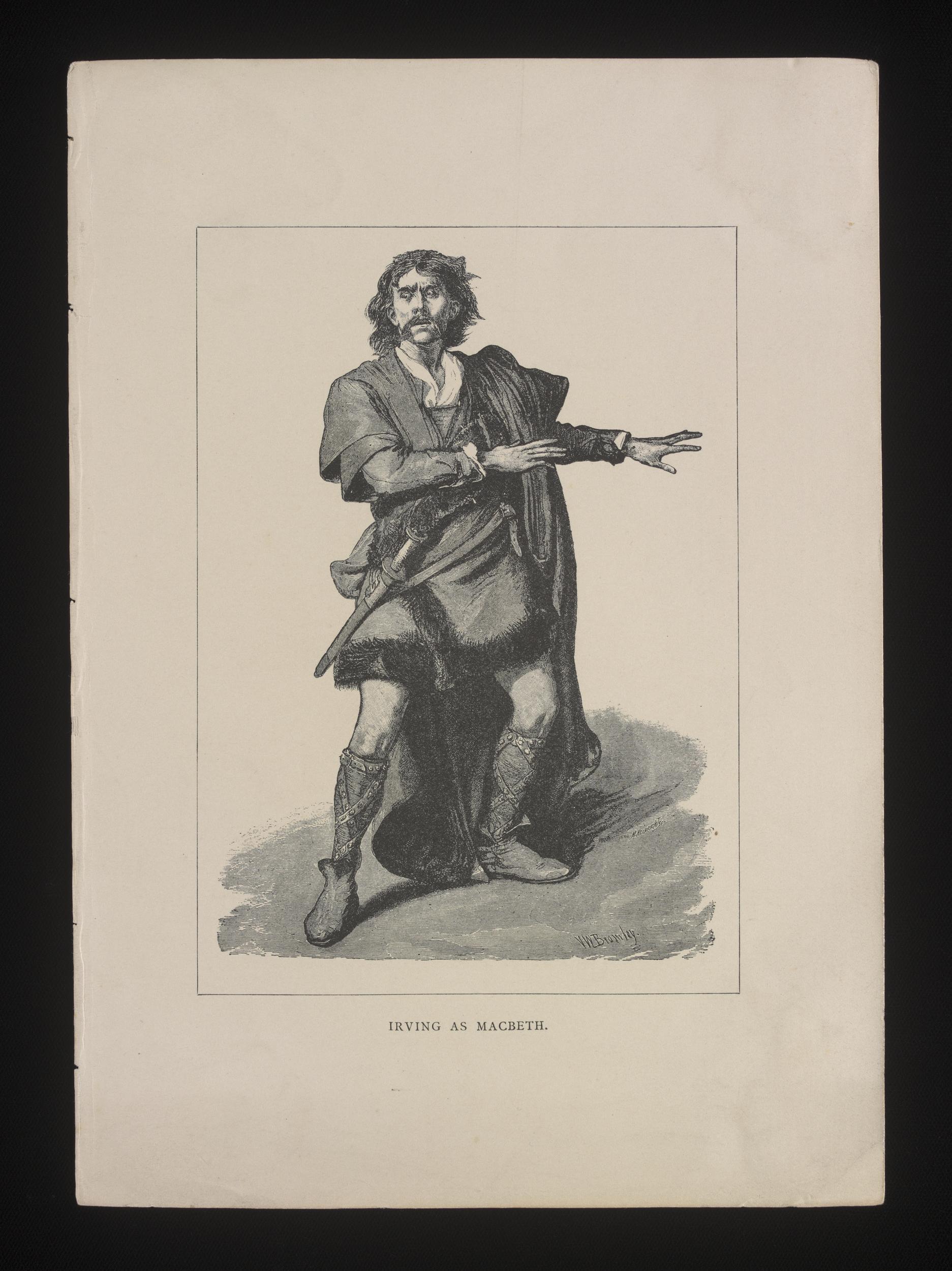

Print of Henry Irving as Macbeth by an unknown engraver. Harry R. Beard Collection, given by Isobel Beard ©Victoria & Albert Museum, S.506-2013.

Audiences wanted to see Terry in comic roles such as Rosalind in As You Like It, a role she never had the opportunity to perform. The announcement that she was instead to play Shakespeare’s ambitious murderess—Lady Macbeth—provoked great debate.

Many people felt Terry’s “gentle womanliness” would make it impossible for her to portray Lady Macbeth’s “diabolical and fiendish” qualities.2 Undeterred, Terry remained determined to present her own, carefully researched, interpretation of the role which would demonstrate that there was “more to [her] acting than charm.”3

Irving was equally committed to his performance of the traitorous Macbeth. He maintained this commitment despite the criticism levelled at an earlier performance of his in the role of Macbeth in 1875. Irving believed that Macbeth was a “moral coward” and “a villain cold-blooded, selfish, remorseless […] a man of sentiment and not of feeling,” and prepared for his part accordingly.4

“When I think of his ‘Macbeth,’ I remember him most distinctly in the last act after the battle when he looked like a great famished wolf, weak with the weakness of a giant exhausted, spent as one whose exertions have been ten times as great as those of commoner men of rougher fibre and coarser strength…”

— Ellen Terry, The Story of My Life, 1908, pg 303

Anxious to ensure “complete accuracy in every particular detail” of his production, Irving engaged the antiquarian and painter Charles Cattermole (1832-1900) to design the set and all the costumes except those worn by Terry, who had her own designer.5

Cattermole spent over a month seeking out “authoritative” sources for costume, decoration and architecture in London Museums. The “[…] vessels in the banquet scene were exact copies of originals in the British Museum, and the patterns for some embroideries came from an eleventh century cope [cape] in the South Kensington Museum.”6

Irving carried out equally extensive research. He and Terry travelled to Scotland to examine the “blasted heath” on which Macbeth first encountered the witch, only to find instead “a flourishing potato field.” Fortunately, their investigations into the history of the period proved more successful and, having discovered that “Macbeth was slain by Macduff on December 5, 1056,” Irving chose to set the production in the 11th century.7

The scene painters Hawes Craven (1837-1910) and Joseph Harker (1855-1927) were then instructed to create backdrops which would conjure up a Celtic/Anglo Saxon vision of Scotland.

The lights rose again to reveal Lady Macbeth seated in a chair before the fire, a letter from Macbeth grasped in her hands…it was not Terry’s opening speech which mesmerized audiences, but the emerald green costume in which she first appeared.

The Lyceum production of Macbeth opened on the 29th of December, 1888. The curtains rose to reveal a stage immersed in darkness, thunder, and rain. A sudden flash of lightening revealed the Weird Sisters silhouetted against the sky; flying through the air, they finally landed on a “rocky eminence.”8

This eerie and dramatic opening established the dark mood of the play. It also signalled Irving’s rejection of earlier stage tradition. This was no comic trio of male performers imitating crones. Instead, Irving cast three established female performers, presenting them as disturbing, inhuman figures that relished the tragedy ahead.

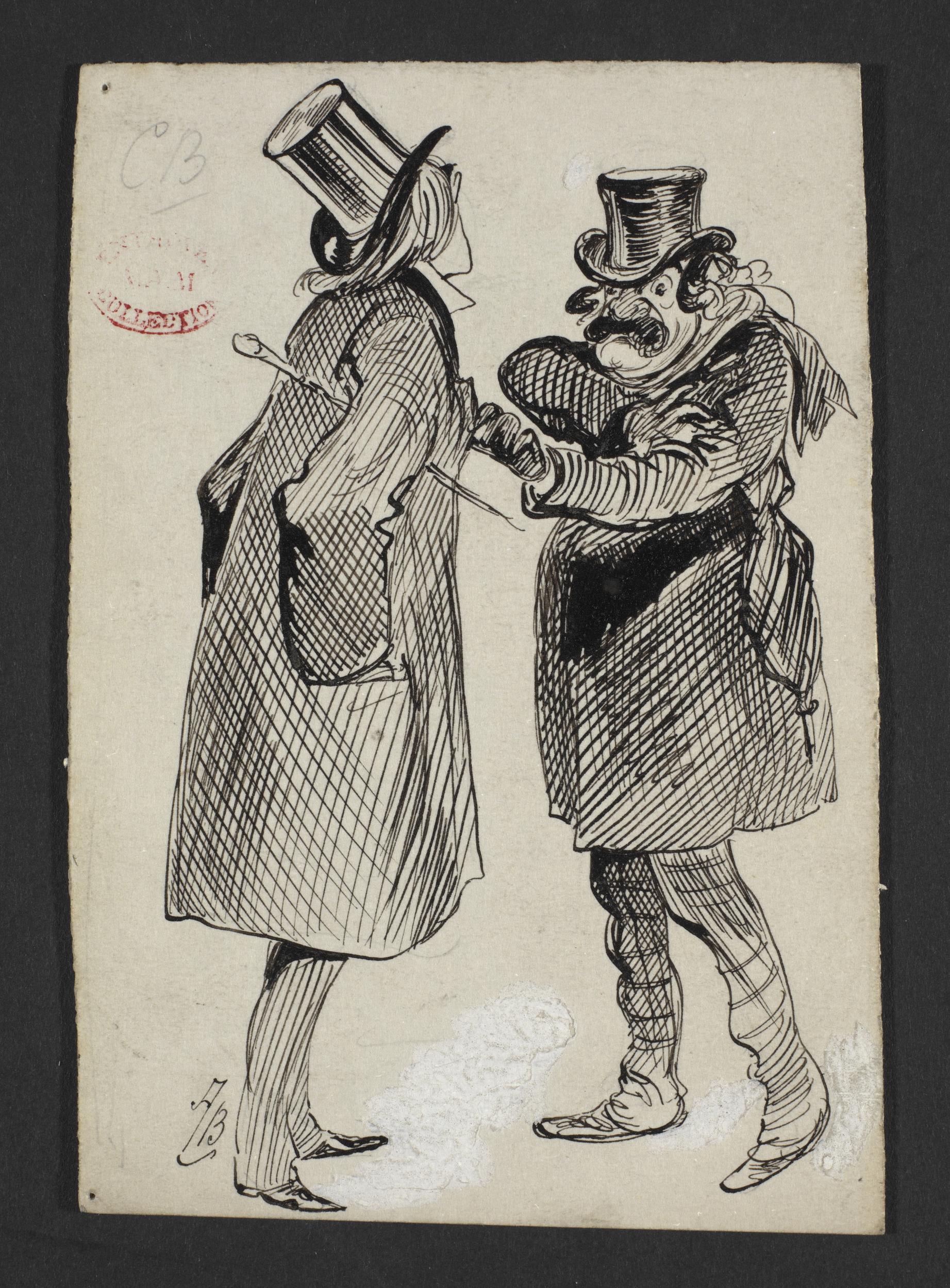

Alfred Bryan’s caricature of Irving (left) and Sullivan (right). Gabrielle Enthoven Collection, ©Victoria & Albert Museum, S.938-2012.

Music played a crucial role in heightening the dramatic effect of the production. Sir Arthur Sullivan (most famous for his partnership with the librettist Sir W.S. Gilbert, of the Gilbert & Sullivan comic operas), produced a score which expertly established the shifting mood of each scene, foreshadowing the doom of the play’s ruthless protagonist. The “wild, demoniacal” melody Sullivan composed for Macbeth’s second encounter with the witches provided the perfect counterpoint to a dramatic scene set against “blood dripping skies” and lit by flashes of fire from a bubbling cauldron.9 It would be highly praised.

As the witches delivered their predictions, drum beats heralded the arrival of Macbeth. Recognizing that before them stood a man willing to kill to gain the crown, the witches intensified Macbeth’s lust for power. Disturbed but pleased by their prophecies, Macbeth led his soldiers away across the heath and the stage went black.

Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, seated by the fire in the opening scenes of the play. She wears the elaborate dress Alice Comyns Carr designed for her. Guy Little Collection, ©Victoria & Albert Museum, S.133.441.2007.

The lights rose again to reveal Lady Macbeth seated in a chair before the fire, a letter from Macbeth grasped in her hands. She rejoiced in the news it provided of her beloved husband’s royal destiny. However, it was not Terry’s opening speech which mesmerized audiences, but the emerald green costume in which she first appeared.

Terry had her own costume designer, as was deemed appropriate for the leading lady of the Lyceum. By 1888, Alice Comyns-Carr had taken on this role, and her goal in this production had been to create a dress as “like soft chain armour as [she] could, and yet […] give the appearance of the scales of a serpent.”10

Inspired by historic engravings in Notre Dame cathedral, Terry’s gown was crocheted from fine yarn with “a twist of soft green silk and blue tinsel,” which her costume maker, Ada Nettleship, had sourced from Bohemia. The cuffs of the wide, hanging sleeves, and the hem, were bordered with “Celtic designs” and decorated with red and white cut glass “jewels.” The costume was still not felt to be “brilliant enough,” and so the entire surface was covered with beetle-wing cases, which glistened in the gas-light.11

Though the “divine beauty” of Terry’s costumes won over many sceptical critics, others remarked on the contrast between her elaborate garments and the simple knee-length tunics and wool cloaks worn by other performers (including Irving).

Oscar Wilde observed that “Judging from the banquet, Lady Macbeth seems an economical housekeeper, and evidently patronizes local industries for her husband’s clothes and the servant’s liveries; but she takes care to do all her own shopping in Byzantium.”12

The full magnificence of Terry’s costume became apparent in the next scene. A heather-colored cloak, decorated with fiery griffins, was now added to the ensemble; beneath this the glittering skirts of the beetle-wing dress swept out behind Terry as she strode out of the castle to greet the old King.

King Duncan’s arrival at Macbeth’s castle gave Irving a further opportunity to showcase the talent of the scene artists. The scene took place by moonlight and was illuminated by burning torches. Hawes Craven recreated a huge stone castle at the top of a steep ramp, which the King and his retinue climbed to reach the gates.

Meanwhile Macbeth and his wife waited at the castle entrance, the serene and beautiful music accompanying this meeting, disguising their planned treachery. The scene entranced spectators and provided the original inspiration for John Singer Sargent’s (1856-1925) portrait of Terry as Lady Macbeth (1888-9).

Conscious that Duncan’s murder marked a key turning point in the play, Irving commissioned another ambitious set from Hawes Craven. This courtyard included a round tower with a spiral staircase to Duncan’s room and a gallery which ran along two sides of the courtyard. The pace of the production — and tension — increased during this scene. The stage remained in shadow, with figures bearing torches rushing in and out of the space at both ground and gallery level.

Two figures stood out against the shadows: Macbeth, his murderous intent foreshadowed by a vivid scarlet cloak (originally created for Terry), and his loyal wife, who was prepared to overcome her fear and “screw [her] courage to the sticking place” in order to further her husband’s ambitions and conceal his crime.

The elaborate gold and cream costumes in which Macbeth and his Queen reappeared for the Banquet Scene (Act III of Irving’s text) highlighted their new royal status. Critics were once again dazzled by the splendor of Terry’s wardrobe. They were less impressed, however, by the way Irving managed the key event in this chilling scene – the arrival of Banquo’s ghost.

Choosing realism over effect, Irving featured a ghost played by an actor, who emerged through a trick chair before joining the guests at the table. Whilst it was feasible that Macbeth’s guests might have been oblivious to the “ghost” who tormented their new King, the Lyceum’s audiences were not convinced. It did not help that the all-too-solid spectre had to exit the stage in crouching position, attempting to “vanish” from sight. The failure of this pivotal moment provoked disappointed howls from spectators. Recognizing this, Irving replaced the physical apparition with a spectral shaft of blue limelight soon after the opening night.

Creating tension and unease at the Banquet was essential, as the scene heralded both the growing isolation of Macbeth and the ensuing madness of his wife.

Tormented by guilt: Ellen Terry as she appeared in the sleepwalking scene, ©Victoria & Albert Museum, S.133.440.2007.

Tormented by her part in Duncan’s murder, Lady Macbeth was next seen pacing frantically through the cloister of the castle, her white nightdress and auburn hair dishevelled and a lamp in her hand. Spectators were mesmerized by Terry’s performance in this scene, which held them “in a state of absolute, almost painful, stillness”13 so intense, that after her final exit, “the house [recovered] itself with an effort, as if it had been hypnotized.”14

In deliberate contrast to the gentle tragedy of the previous scene, the final act increased pace as events accelerated towards the dramatic climax. Irving oversaw five increasingly swift scene changes, each one masked by large groups of soldiers marching across the stage. The action alternated between the approaching troops and the figure of Macbeth, preparing to defend his castle against their attack.

However, the Macbeth waiting anxiously at his castle gates was not the triumphant soldier of his youth. Instead, the Lyceum production emphasized the years which had passed since the protagonist’s initial rise to power. Exhausted by the strain of maintaining his position as King, Irving’s Macbeth was an old, weak, and deeply flawed man. These signs of humanity and moral cowardice did not please critics, but they were crucial to Irving’s understanding of Macbeth.

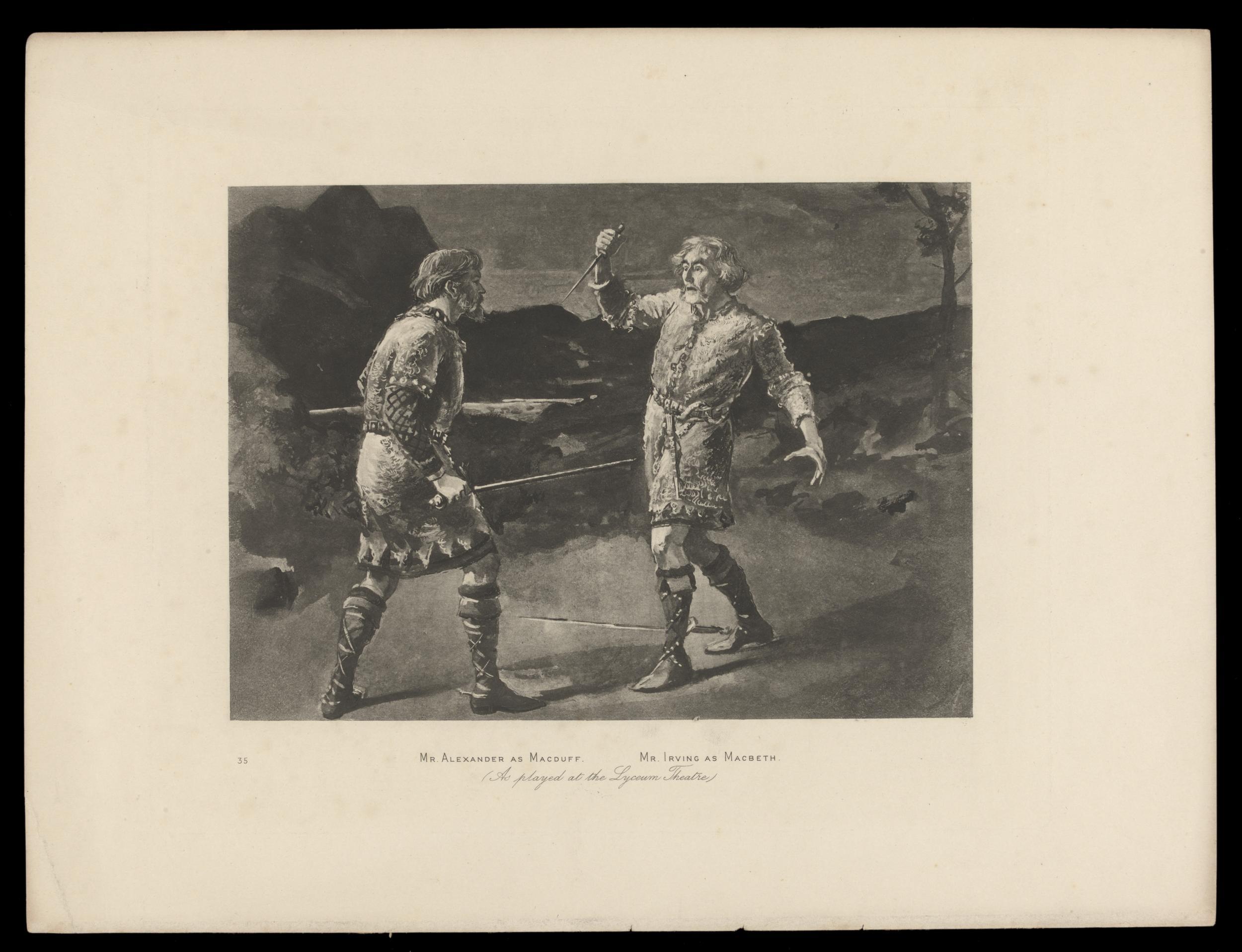

Henry Irving as Macbeth and George Alexander as Macduff during Macbeth‘s climax, unknown artist, Victoria & Albert Museum, S.2460-2009.

The fatal duel between Macduff and Macbeth, which ordinally provides the climax of the play, was unspectacular, and Irving deliberately drew attention away from the corpse of the vanquished Macbeth (who lay face down and forgotten), towards the new ruler: Malcolm. The play concluded with a loud cry of “Hail, King of Scotland,” and, as the stage was plunged into darkness, the applause began.

“It is a most tremendous success, & the last 3 days booking forward has been greater than ever was known, even at the Lyceum….Some people hate me in it – some (Henry amongst ’em) think it my best part – & the critics differ, and discuss it hotly, which in itself is my best success of all!!!…Oh, dear It is an exciting time at the Lyceum I tell you!”

— Ellen Terry, in a letter to daughter Edith Craig, January 3, 1889 (V&A THM/384/1/4)

Although critics were divided by the controversial interpretations of the lead roles, almost all were united in their praise for the spectacle and power of the production. The initial run lasted one hundred and fifty nights, finishing in June 1889. For many, Macbeth marked the pinnacle of Irving and Terry’s professional partnership.

PREVIOUS: Discover the sensational night of performances in German and English just after the American Civil war in Boston.

NEXT: Travel across Australia with the country’s first Shakespeare touring company.

- Meisel, Martin, Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984, 402-405.

- “The Real Macbeth,” Unidentified periodical, ca. December 1888, Press Cutting, mounted in Percy Fitzgerald Albums, Volume V: 311, Garrick Collection, London.

- St John, Christopher, Introduction to Terry, Ellen, Four Lectures on Shakespeare, London, Martin Hopkinson, 1932, 13.

- Hughes, Alan, Henry Irving, Shakespearean, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981, 92-3.

- Comyns–Carr, Alice and Eve Adam, ed., Mrs. J. Comyns Carr’s Reminiscences, London: Hutchinson & Co. Ltd, 1926, 149.

- Booth, Michael, Victorian Spectacular Theatre 1850-1910, London: Routledge, 1981, 46-7.

- “Interview with Charles Cattermole,” Pall Mall Gazette, December 31st 1888: 5. Percy Fitzgerald Album, Volume V: 317, Garrick Club, London.

- Hughes, Alan, Henry Irving, Shakespearean, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981, 94.

- Hughes, Alan, Henry Irving, Shakespearean, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981, 109-110.

- Comyns–Carr, Alice, Mrs. J. Comyns Carr’s Reminiscences, London: Hutchinson & Co. Ltd, 1926, 211-212.

- Comyns–Carr, Alice, Mrs. J. Comyns Carr’s Reminiscences, London: Hutchinson & Co. Ltd, 1926, 211-212

- Manvell, Roger, Ellen Terry, London: Heinemann, 1968, 198.

- Hughes, Alan, Henry Irving, Shakespearean, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981, 112.

- Unknown author in The Times, December 1888, Chronicles of the Lyceum Theatre vol. 2, The Garrick Club Collections, BOOK10780.