Toggle the map to discover the details of the Wilkie Shakespeare Company tours of Australia and New Zealand, with data collected from the AusStage database. Scroll down to learn more about the Company’s journey.

“…when the cheers had abated Mr. Allan Wilkie in a short speech, thanked the audience, on behalf of himself and his company. The season, he said, had been by far the most strenuous of all their seasons in Tasmania, and at the same time the most successful.”1

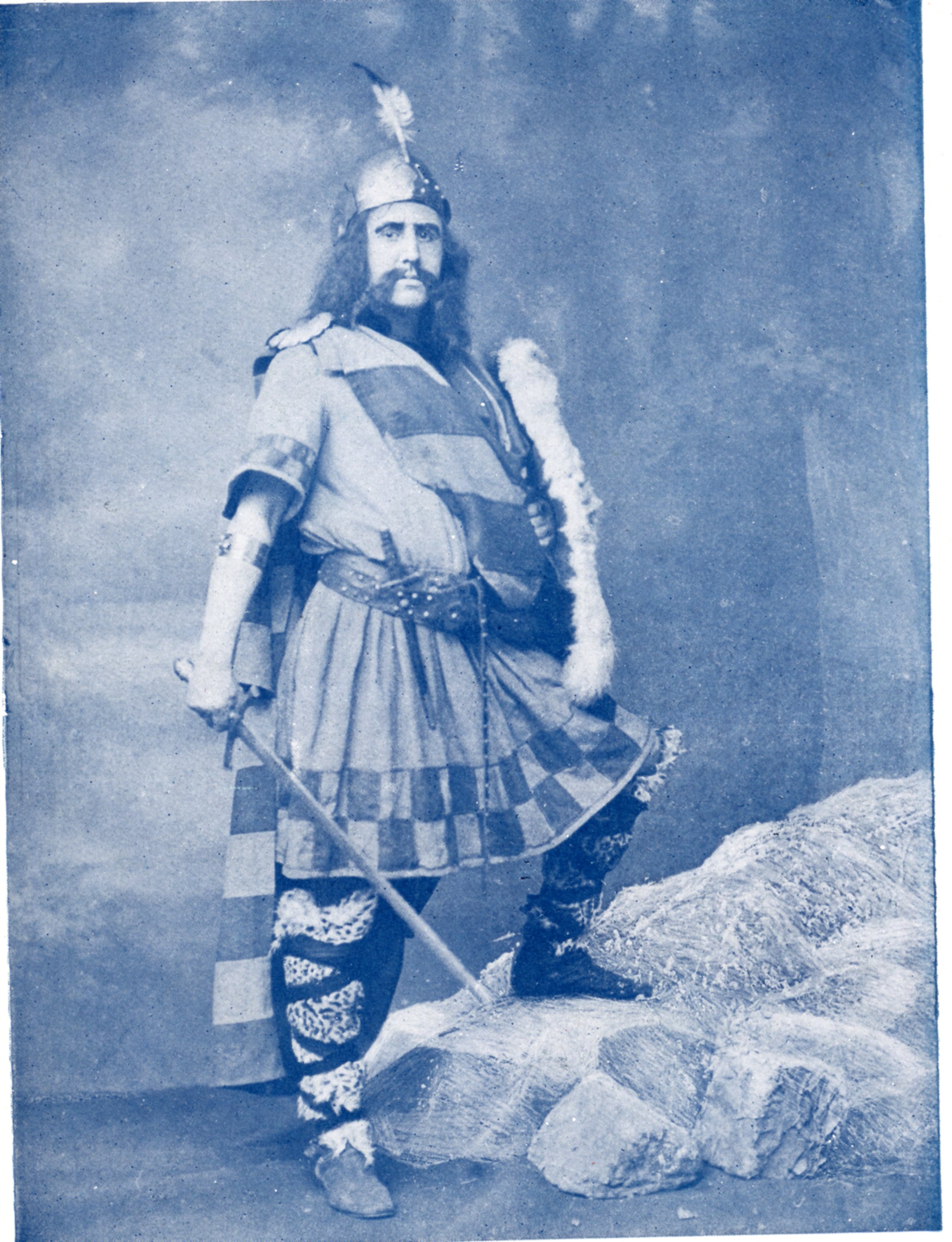

Stirling Studios, Photographer. Portrait Photograph of Allan Wilkie / Stirling., 1922. State Library Victoria, Accession no: H2016.382/5.

Allan Wilkie, one of the last great actor-managers in the Henry Irving tradition, founded the first permanent Australian touring Shakespeare company in 1920. He proudly promised “an exceptional powerful company of forty artists, a greatly augmented orchestra and a magnificent new wardrobe, with novel scenic effects, [that] will contribute towards the grandest and most impressive revival of Shakespeare’s sublime tragedy.”2 He began with a production of Macbeth at the Princess Theatre in Melbourne, in the state of Victoria. Within the next four years, he had staged over 1000 performances of Shakespeare’s plays. The Australasian newspaper had observed of Wilkie a few years previously,

If the younger generation of theatre goers trouble their heads at all about the impressions or perplexities of the past, they must sometimes pause to wonder how, where and when the conclusion that in theatrical enterprise Shakespeare spells ruin was established… Mr. Allan Wilkie came to a neglected theatre and wholly by his own special aptitude for certain Shakespeare characters established himself for a long and successful season… The old verdict needs revision, for Shakespeare in fair measure has in recent years spelled success.3

Born in Liverpool in 1878, Wilkie debuted and learned his trade in the companies of the great British Shakespearean actors of the last part of the nineteenth century, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Ben Greet and Frank Benson. By 1905, he was touring his own troupe around England, South Africa, India, China and Japan. Rather than return to a Europe in the agony of world war, he migrated to Australia in 1914 with his actress wife, the splendidly named Frediswyde Hunter Watts, arriving in 1915.

Stirling Studios, Photographer. Portrait Photograph of Actress Frediswyde Hunter-Watts / Stirling., 1922. State Library Victoria. Accession no: H2016.382/4.

In her memoirs, Dame Ngaio Marsh describes Wilkie as an actor with “a grand declamatory manner”4 and Hunter Watts as “delicate, gentle, with a cloud of bronze hair and strangely moving break in her voice”.5

For his first few years, Wilkie worked as an actor with the established Australian touring theatre firms of Nellie Stewart and JC Williamson. In 1916, however, he was made head of George Marlow’s Grand Shakespearean Company and given a free hand in choice of play and style of production.

Perhaps it was at this moment he formed the ambition to personally present all 38 of Shakespeare’s plays. By the time the Wilkie Shakespeare Company ceased operation in 1930, he had staged 27 of them.

When disaster struck in 1926, Wilkie saw evidence of how successful he had been in connecting Shakespeare to the lives of the Australian public.

Wilkie was a traditionalist in his approach to staging Shakespeare, and a painstaking interpreter of the plays themselves, so much so that more experimental adaptations like Barry Jackson’s modern dress production of Cymbeline at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in 1923 left him aghast. John Golder comments on Wilkie’s approach as follows:

Wilkie showed himself the scholar in his concern for textual authenticity. He omitted the Hecate scenes from his 1920 Macbeth on the grounds that they were ‘probably by Middleton’ and sought advice regarding the authorship of Act 1, scenes 1 and 2 before deciding to include them. Later, in the Shakespearean Quarterly, a ‘house journal’ which he published between 1922 and 1924, he defended Hazlitt’s sympathetic view of Shylock. But, whilst he aimed to make the plays as useful as possible to students and scholars, Wilkie was no less anxious to show the theatre-going public that Shakespeare was ‘not an academic pedagogue, but a popular dramatist’. To this end he accentuated such opportunities as the plays offered for broad comedy and for the introduction of music and song.6

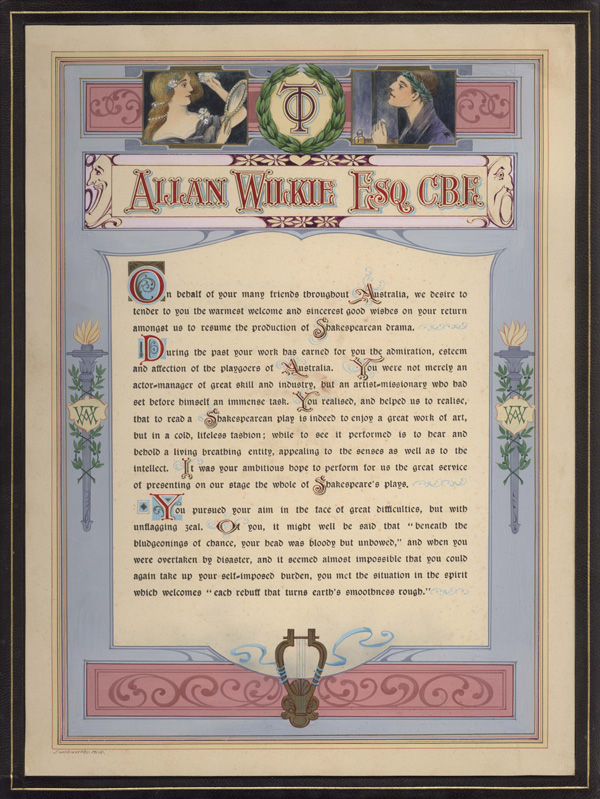

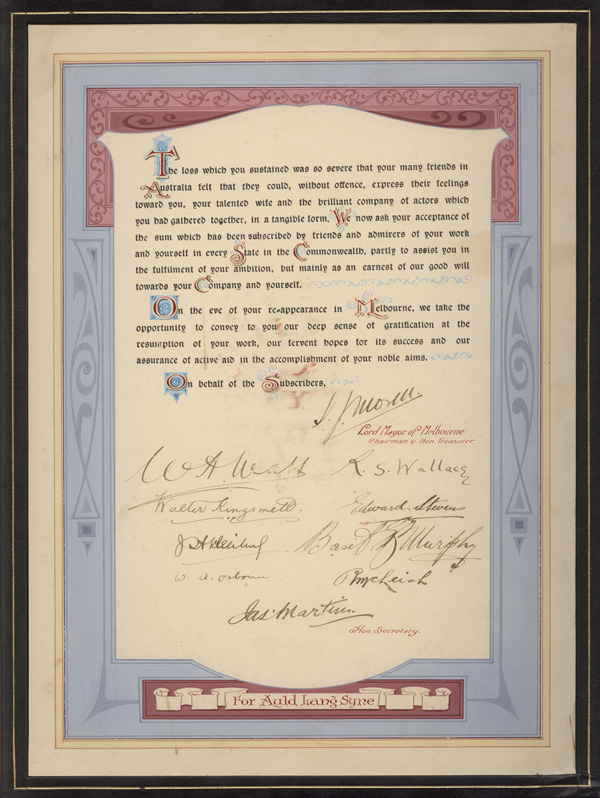

When disaster struck in 1926, Wilkie saw evidence of how successful he had been in connecting Shakespeare to the lives of the Australian public. The company’s scenery and costumes were destroyed in a warehouse fire in the coastal town of Geelong. A national fundraising campaign facilitated his return to London to buy new ones, and by the following year the company was back on the road, opening a summer run of Macbeth in Australia’s southern-most (and therefore coolest) state, the island Tasmania.

After the Geelong fire, Wilkie’s Australian admirers presented him with the following award celebrating his troupe’s return to the stage.

Over the seven years of producing Shakespeare, Wilkie’s staging approach changed. With so much traveling to do in the days before air travel—the first commercial passenger flights did not occur in Australia until the 1930s—it was imperative that everything the company needed for its popular productions was portable and easy to pack. That meant featuring sumptuous costumes on a minimal set, using only the props strictly necessary for the action of the chosen play. This approach also had the advantage of flexibility, so Wilkie’s company could adapt their productions to the wide variety of venues they faced in their peripatetic wanderings across the vast expanse of regional and metropolitan Australia.

After 1927, however, Wilkie’s taste became more judicious. Electric lighting was used to better effect, side curtains were replaced by proper wings, and new painted backdrops were commissioned. Wilkie explained to the Hobart Mercury that,

All the stage settings have been devised with much brighter coloring and the whole scheme is designed to get a highly pictorial effect and to blend with the gorgeous costumes to which it forms a fitting background. It is impossible to give convincingly realistic scene on the stage… My whole aim with the new settings is to give a symbolic and suggestive effect… The scene artist always works with the knowledge that the electrician’s art will bring out different color effects.”7

The Mercury noted the appreciation of the Tasmanian audience, and their review of Macbeth gives a sense of the high place that the company had won in the hearts of Australians after many years of continual touring: “The Theatre Royal was filled to overflowing with an intensely appreciative and enthusiastic audience last night, when the Allan Wilkie Company gave Macbeth as a farewell performance…There was loud and generous applause as a mark of appreciation of each of the many powerful scenes, and at the end of the play a perfect storm of enthusiasm broke loose…”8

The company can also claim to be the first to attract serious government subsidy, as Wilkie persuaded a number of Australian states—though notably not Victoria—to provide it with free train travel.

Wilkie worked with all the major Australian actors of his day, though he and his wife took the leading roles in the company’s Shakespeare productions. (This was not always to Wilkie’s advantage—as a large-framed thirty-seven-year-old he was unsuited to role of Romeo, for example).

Wilkie was not always an easy person to get on with as a producer, but he was a brilliant promoter of the company, and of Shakespeare generally, with a particular eye on schools’ audiences. In 1925 he was awarded a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) for his services to theater, particularly in respect of education. The company can also claim to be the first to attract serious government subsidy, as Wilkie persuaded a number of Australian states—though notably not Victoria— to provide it with free train travel.

As conventional as Wilkie’s Shakespeare productions might have been in their design, they were adventurous in their use of accompanying music. In fact, it is possible to argue that his openings were as much musical events as dramatic ones. Lisa Warrington, the most detailed of Wilkie’s historians, notes that the company travelled with a musical director throughout its decade of existence.

His main job was to direct the orchestra which supported all Wilkie’s productions, providing overtures and entr’actes, and playing incidental music wherever appropriate… Extant music was used where possible – for example, Mendelssohn was always play[ed] for performances of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Nicolai for The Merry Wives – but where necessary, [the musical director] would compose his own pieces, such as the march for Julius Caesar. The components of the orchestra would vary from one venue to another. In the mainland capitals, local musicians were hired, to provide a competent orchestra of perhaps a dozen instruments. In the small towns, there might be found only one or two musicians who were capable of working with little or no rehearsal.9

By 1930, the combined impact of the Great Depression and the introduction of sound films took a fatal toll on the company’s box office, and by October of that year it was effectively out of business. For a further year, he and Hunter Watts survived by reciting Shakespeare in country towns before they left Australia in September 1931 to spend the rest of their lives in Canada, the United States of America, and Britain.

“…virtually single-handed, he introduced the plays of Shakespeare to an entire generation of Australian theatre-goers…”10

The Australian Dictionary of Biography describes Wilkie as: “An impressive figure… with a moon-shaped face, [Wilkie] could command the stage, and his portrayals were usually thoughtful and effective. As a director, he combined skill and vision. A romantic and anti-modernist, he saw the practical advantages of simpler staging of Shakespeare which allowed for more pace and textual authenticity.”11 Warrington writes,

Wilkie’s work throughout the 1920s marked the first serious attempt to establish a permanent Shakespeare company in Australia, all the more remarkable because it was an independent venture which for many years received no financial assistance, and was in open competition with the popular offerings of commercial theatre firms. [His] main contribution to Shakespeare production lay in the fact that, virtually single-handed, he introduced the plays of Shakespeare to an entire generation of Australian theatre-goers, and in the process made a significant contribution to establishing a tradition of classical acting in Australia.12

PREVIOUS: Discover the celebrity partnership that lit up the London stage in the late 1800s.

NEXT: Explore the landmark all-black production of Macbeth directed by Orson Welles.

- “ALLAN WILKIE SEASON. ‘Macbeth.’ Enthusiastic Farewell.” The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), Feb 8, 1927. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/29662472.

- “ALLAN WILKIE and Miss Hunter-WATTS in Macbeth.” The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), Sep 8, 1920. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/4585165.

- “Theatres, &c.” The Australasian (Melbourne, Vic. : 1864 – 1946), Aug 25, 1917. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/140193794

- Marsh, Ngaio, Black Beech and Honeydew, London: Collins, 1966, 141.

- Marsh, Ngaio, Black Beech and Honeydew, London: Collins, 1966, 125.

- Golder, John. “A cultural missionary on tour: Allan Wilkie’s Shakespearean Company, 1920-30,” In O brave new world: Two centuries of Shakespeare on the Australian stage, edited by John Golder and Richard Madelaine, Sydney: Currency Press, 2001, 123.

- “THE PLAYHOUSE: Mr. Allan Wilkie New Productions Unique Stage Settings.” The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), Dec 22, 1927. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/24195449.

- “ALLAN WILKIE SEASON. ‘Macbeth.’ Enthusiastic Farewell.” The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), Feb 8, 1927. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/29662472.

- Warrington, Lisa J.V, “Allan Wilkie in Australia: the work of a Shakespearean actor-manager,” PhD diss., University of Tazmania, 2007, chapter IV, np.

- Warrington, Lisa J.V, “Allan Wilkie in Australia: the work of a Shakespearean actor-manager,” PhD diss., University of Tazmania, 2007, Preface, np.

- Rickard, John. “Wilkie, Allan (1878-1970).” Australian Dictionary of National Biography, 1990. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/wilkie-allan-9096/text16039.

- Warrington, Lisa J.V, “Allan Wilkie in Australia: the work of a Shakespearean actor-manager,” PhD diss., University of Tazmania, 2007, Preface, np.