3.5 Errors

This section sets out to demonstrate the presence of error and the correction of error in the hands of both Carington and Dering. It presents an object lesson in how a text can become inaccurate, in ways that can be distinguished from the purposeful processes of transcription and adaptation. It also demonstrates the inscribers’ determination to correct error, and the occasional failures of correction itself.

There is nothing unusual in these mistakes and corrections, and indeed the examples constitute an anthology of various phenomena that are widespread in early modern manuscript culture, and in all practices of human reading and copying. However, the examples take us deeply into the actuality of making one particular script and the variable kinds of attention its makers bestowed on it.

Carington’s Uncorrected Errors

Example 1

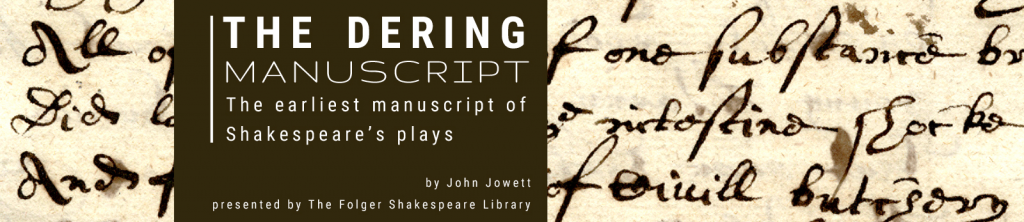

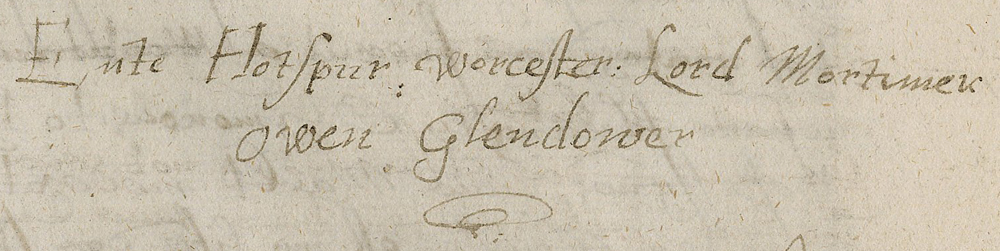

Carington writes “Ente” for “Enter.” This is not a known spelling of the word. But Carington might have thought it valid, as he repeats the form. In 1623 there were no standard dictionaries in which to check spellings. Some authors and scribes produced highly idiosyncratic forms, though Carington’s spellings were usually common and recognizable.

Example 2

Uncorrected dittography. The quarto’s “then the” is expanded to “then then the”. This occurs soon after an error discussed below in which Carington at first accidentally omitted two lines.

Example 3

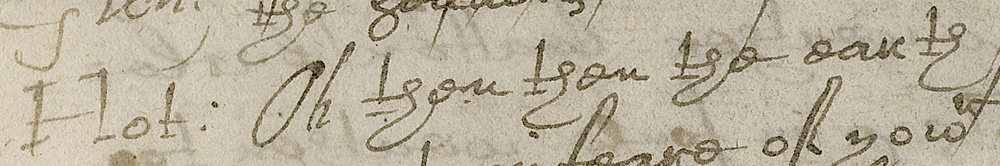

Carington had Falstaff say:

Hall: if thow see me downe in the battell

& bestird me so:, ’tis A point of friendshipe:,

The error “bestird” for “bestride” remained uncorrected. The letters are well formed, so the error is not merely a misplacement of the dot on the “i”. This error would not easily arise from misreading print, but it would easily arise from misreading handwriting. Carington was usually working from print, but this page is part of the section he recopied from his first transcript. He probably copied correctly from print in the first instance, but then misread his own handwriting when preparing a new script of these pages.

It should be admitted that a comparable error occurs when, as far as we know, Carington was working from printed copy, where the quarto’s “trim” was initially copied as a word that might be “turne” (see below). But the reading is uncertain due to its deletion. Moreover, the error Carington identified may have more to do with minim formation (the sequence of similar pen-strokes making the letter sequences such as “rim” and “urn”) than misreading. In any case, the error “bestird” is certainly easier when copying from handwriting.

Errors Carington Corrected Himself

Example 1

Carington accidentally substituted “might” for “may”, but then corrected the mistake. He showed vigilant attention to the detail of his copy in a reading where the error might well go unnoticed.

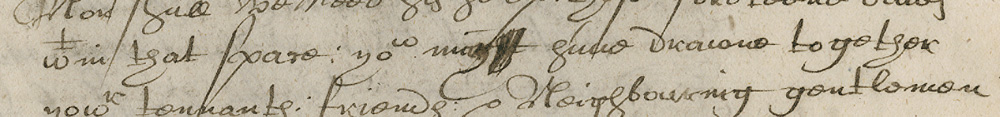

Example 2

Here the printed quarto read “When you are better tempered to attend.” Carington wrote “when you are bettered to attend”, an error of eyeskip from the “er” of “better” to the “er” of “tempered”. He then corrected by deleting “ed to Attend” and adding “tempered to Attend” to the right of it.

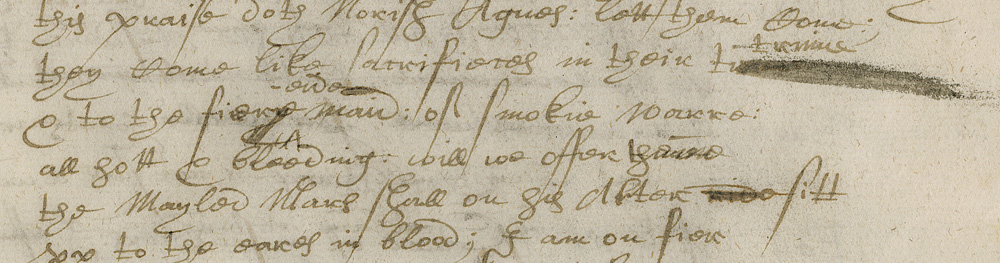

Example 3

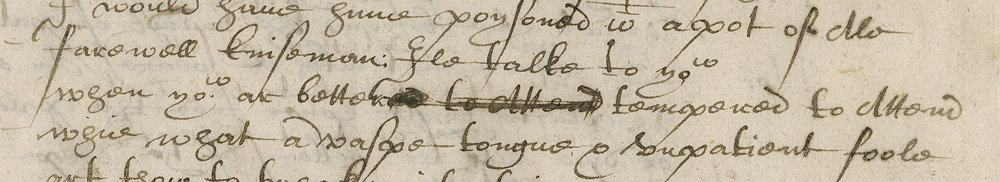

Carington committed three errors within four lines but corrected them all.

1. The quarto’s “trim” became a word now difficult to read in the manuscript due to its deletion. It may have “turne”, though the visible first minim has a dot over it suggesting an “i”. Carington smeared out the word and wrote “trime” above (with an out-of-position “i”) as an interlineation.

2. The quarto’s “fire-eyde” was at first reduced to “firry” (an odd spelling in its own right). In correcting, Carington altered the first “r” to “e” (a correction that might have been made separately before the others) and the “y” to an “e”, making “fiere”; he inserted “-eide” above as an interlineation. The smudge to the right of “-eide” affects a long back-loop on the “d” of the next word “maid”. It may have been smudged to make a nominal separation between the interlineation and the “d”.

3. The quarto “sit” was accidentally altered to “ride”, an error of substitution of one word that fits the context for another. Carington crossed the word out. As the word comes at the end of a line, he was able to write “sitt” to the right of it.

The concentration of errors here is unusual. Carington might have been tired.

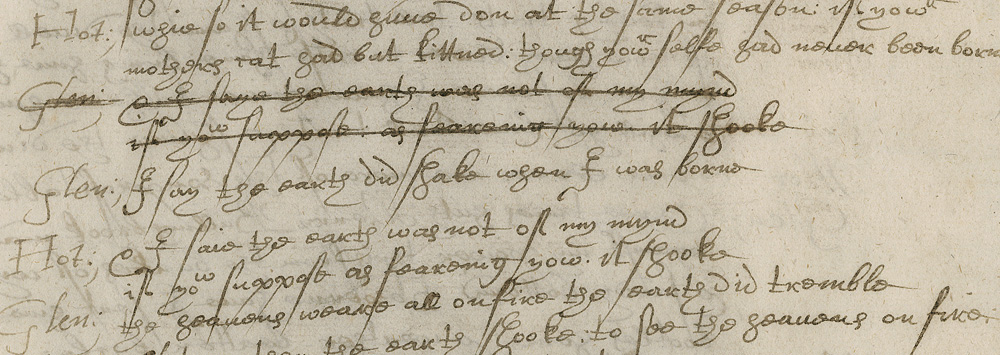

Example 4

Carington here corrects his own error of eyeskip. In Shakespeare, two successive speeches begin with Glyndŵr saying “I say the Earth” and Hotspur saying “And I say the Earth”. After he had written Glyndŵr’s speech prefix for the first of them, Carington’s eye went on to Hotspur’s “And I say the Earth”, causing him to omit Glyndŵr’s words and write Hotspur’s two-line speech, misattributed to Glyndŵr. The mistake must have come to his attention when he saw that the speech he had wrongly attributed to Glyndŵr was followed in the quarto by another speech spoken by the same character. Before proceeding any further, he crossed out the speech prefix for Glyndŵr and the two lines apparently spoken by him, and made a fresh start, writing the speech prefix for Glyndŵr and now following it the that character’s line. Hotspur’s speech was then written out anew, but now correctly attributed to Hotspur.

It will be noticed that this explanation presupposes that the speech prefixes were written at the same time as the speeches that followed them, for otherwise there would have been no speech prefix “Glen:” as was written and then deleted. It might be supposed instead that Carington first wrote the speeches alone and added the speech prefixes afterwards when the page was complete. That is not impossible, but in this case Carington would have noticed the error without writing the speech prefix (which is possible), but later have written in the first speech prefix against deleted lines before realizing this second mistake (which seems very unlikely). In other words, the first speech prefix for Glyndŵr is good evidence that the speech prefix was written before the speech that comes after it.

Dering’s Corrections of Carington’s Errors

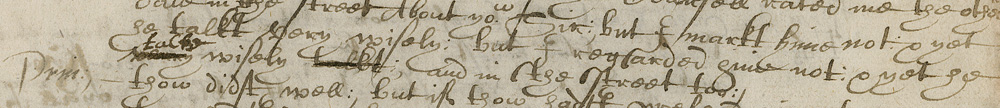

Example 1

Here the quarto reads:

he talkt very wisely; but I regarded him not, and yet he talkt

wisely, and in the street too.

(1 Henry IV (1613), sig. A4v)

Confused by the repetition, instead of writing “and yet he talkt wisely”, Carington wrote “& yet he | very wisely talkt”, thus interpolating “very” from the previous “he talkt very wisely” and transposing “talkt wisely”. Dering restored the quarto readings: he deleted “very”, interlining “talkt” above it, and deleted “talkt”.

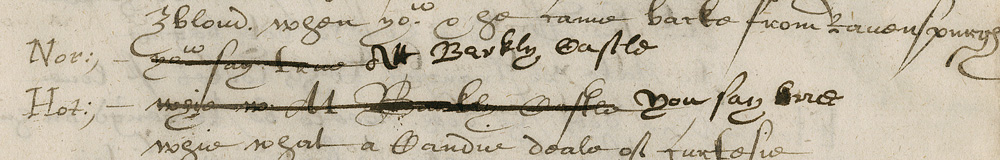

Example 2

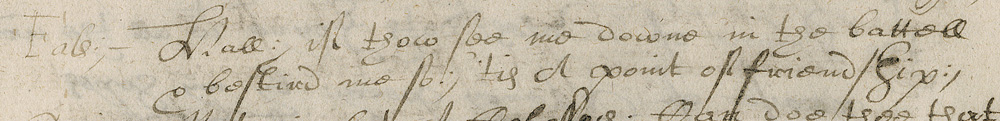

Carington misinterpreted the quarto’s setting of two speeches on one line:

Nor. At Barkly Castle. Hot. You say true,

Why what a candie deale of curtesie,

(sig. C1r)

He reversed their order, and as a consequence he also omitted “At Barkly Castle”. The text now read:

Nor:,– yow say true

Hot:,– whie w

Here Carington stopped, realizing that something was wrong. To correct, he probably deleted “whie w”, and certainly wrote immediately after it “At Barkly Castle”. It is difficult to tell whether Dering or Carington deleted “whie w” because the obvious deletion line as it extends to the right of these letters was mostly if not wholly made by Dering. Close inspection suggests that the beginning of the deletion is in Carington’s ink, which is a lighter brown as compared with Dering’s near black. But as the browner ink appears to extend in a second stroke running right through “At” and into the beginning of “Barkly” before the darker ink predominates, the existence of, and extent of, Carington’s deletion remains uncertain. He probably intended the text at this stage to read:

Nor:,– yow say true

Hot:,– At Barkly Castle

Carington then restarted the line “whie what a Candie deale of curtesie”.

Dering was probably checking the transcript against the quarto when he noticed that this was still wrong. After his alterations, the text as corrected read, as it should:

Nor:,– Att Barkly Castle

Hot:,– You say true

whie what a Candie deale of curtesie

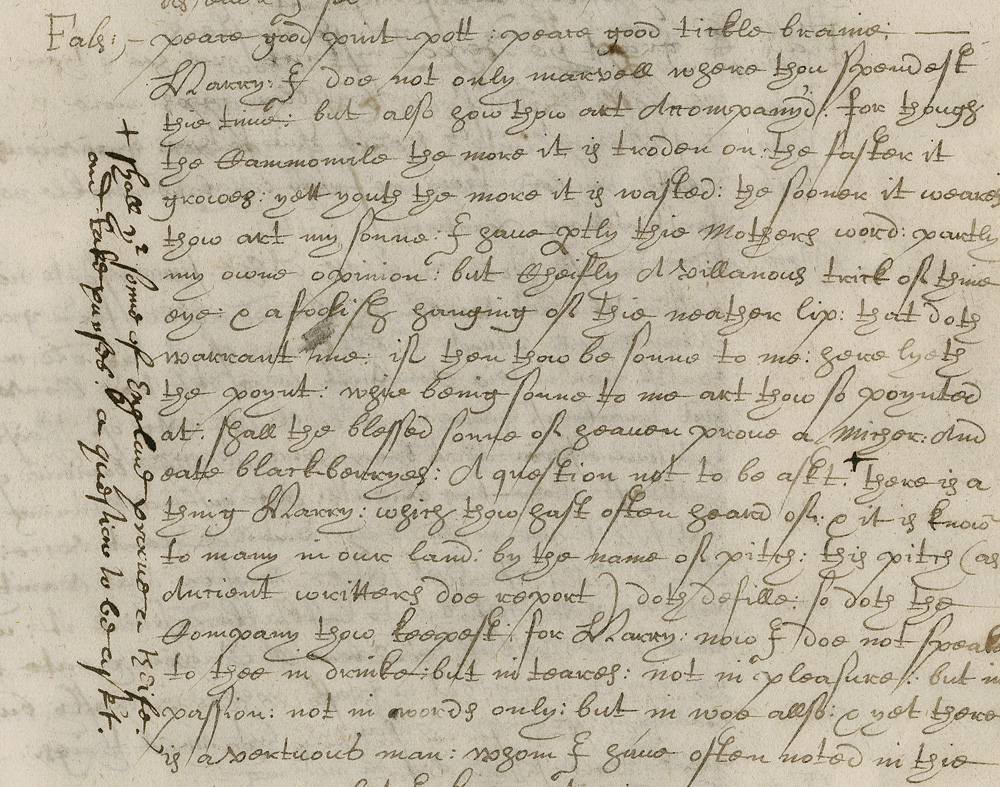

Example 3

Dering here corrects Carington’s eyeskip. He noticed that in copying the play Carington’s eye had skipped from “a question to be askt” to “a question not to be askt”, thus not only losing text but also making nonsense of Falstaff’s speech. As elsewhere, Dering marks the position of the correction by placing a cross in the text (seen just below halfway down the illustrated lines, towards the right), adding a cross in the margin next to his annotation. The cross in the text is placed after “a question not to be askt”. The words Carington omitted, ending with “a question to be askt”, appear written vertically in the margin, below the cross.

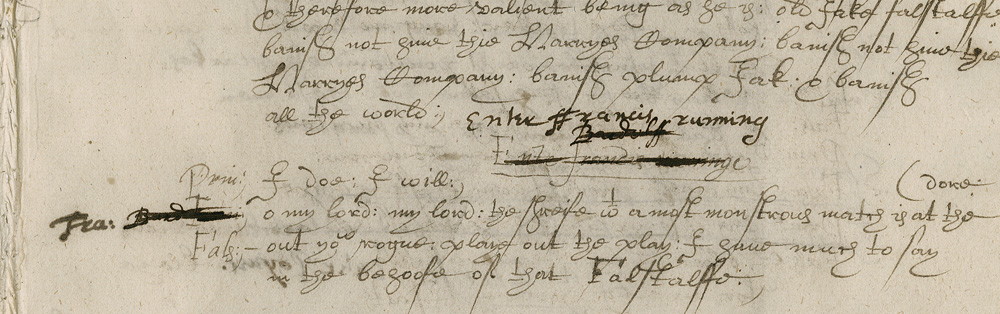

Example 4

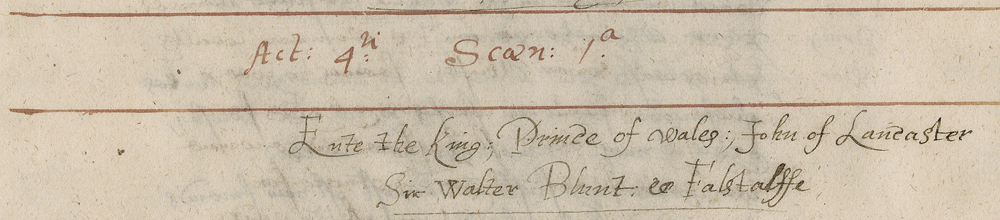

Here Dering miscorrects then re-corrects. His annotations earlier in this long scene aimed at reducing the number of roles have already been discussed in an earlier section. By the time he reached this point he had confused himself. In reviewing the transcript, he may have misrecalled the earlier modifications on fol. 14v in which the role of the Vintner disappears, but the role of Francis is kept even after two rounds of redaction.

Accordingly, he now crossed out “Francis” in the entry direction (his deletion can be seen extending (a) to the left of Dering’s main line over it, below the cross-bar of “F” and (b) between Dering’s two separate lines, through the middle of “i”), replacing it with “Bardolff”, written above the entry. Correspondingly, he crossed out the speech prefix “Fran” and wrote “Bard” to the left of the speech prefix.

He then must have recalled that on the previous page he had added an exit for the Hostess, so that she could re-enter a few lines after the passage shown here, bringing the news that the sheriff and his men were at the door searching for Falstaff. Her exit had left only Poins as the on-stage audience for the role-playing of the Prince and Falstaff as King Henry. Reflecting on this, he would have noticed that Francis is, after all, available to enter here. So he crossed out his first annotation and what remained of Carington’s original stage direction, and now added instead “Enter Francis running” and “Fra:”.

PREVIOUS: Learn what Dering cut from the play and who he casted in different roles.

NEXT: Learn about the historical context of the Dering Manuscript.