3.1 Annotating the Quartos

The Playbooks that were Copied

By early 1623 Dering had already built up a collection of printed playbooks, though there were many more to follow, and his purchases of the Shakespeare and Jonson folios came only towards the end of the year. Dering’s immediate sources for Henry IV were two of these quarto editions.

There had been a succession of seven editions of 1 Henry IV, the most recent of which had been issued in 1622. Perhaps by the time it appeared Dering had already acquired a copy of the earlier 1613 issue, for this was clearly the edition he used. This is evident from the progressive introduction of errors in the reprintings of 1 Henry IV.

How Dering Proceeded

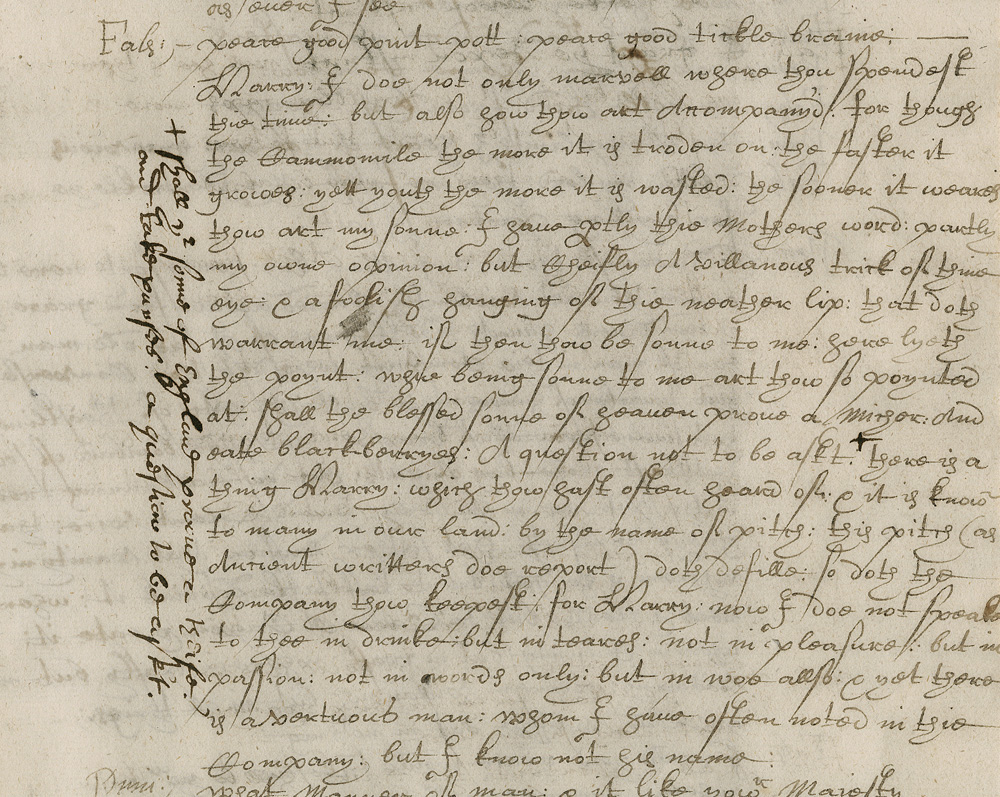

At one point in his annotation of Carington’s transcript, Dering added a note referring himself back to the quarto: “vide printed booke.” (fol. 18v): i.e., see the printed book. He perhaps wanted to return to the quarto to consider restoring lines he had deleted, or needed to check that the transcript was accurate. This note reminds us that Dering himself must have gone through the two quartos from which Carington worked before he handed them over to Carington. How did he advise Carington as to how to construct a text that differed in hundreds of ways from the printed quarto playbooks which he was copying? There seems to be no alternative to him marking up the printed text by hand with deletions, alterations, and additions.

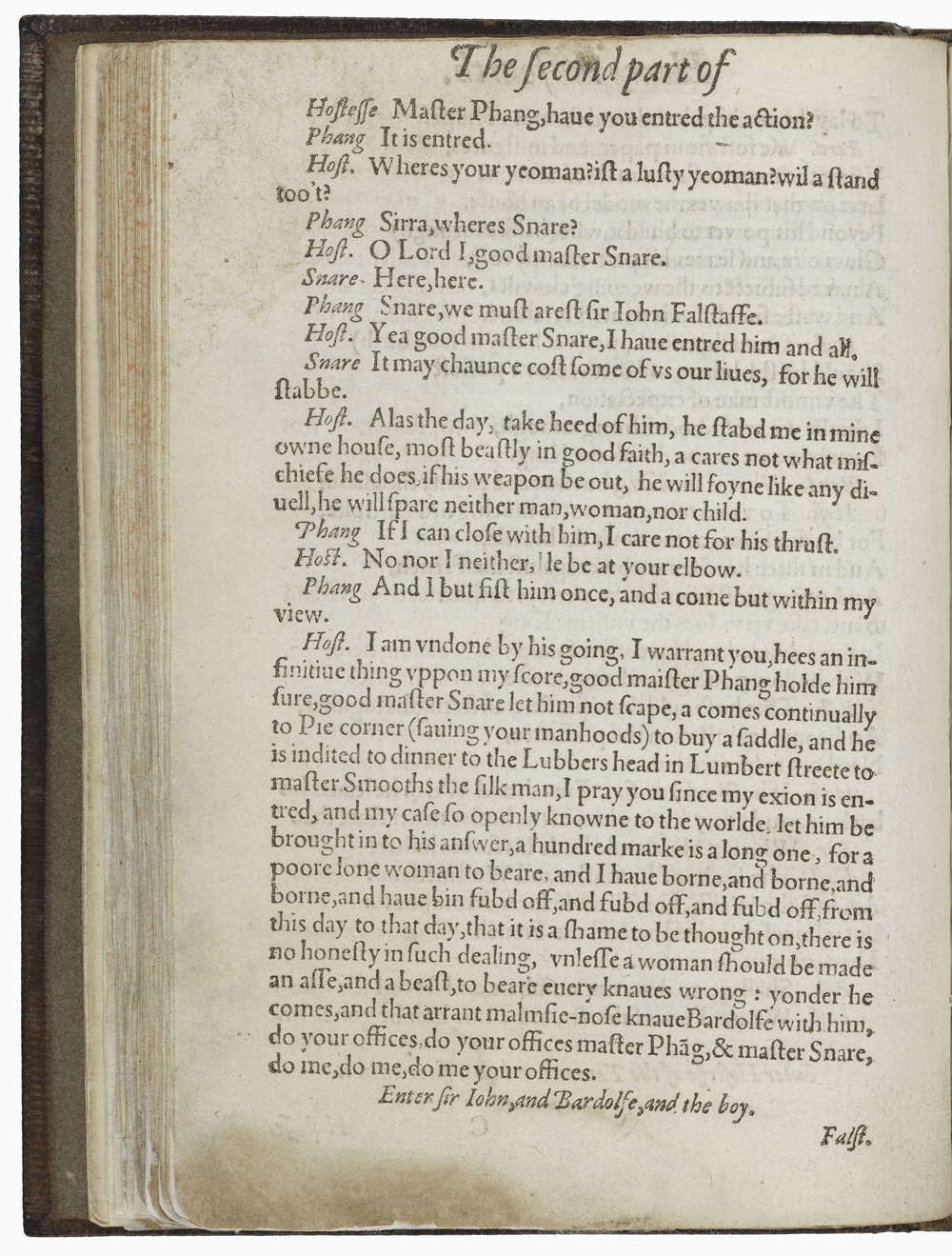

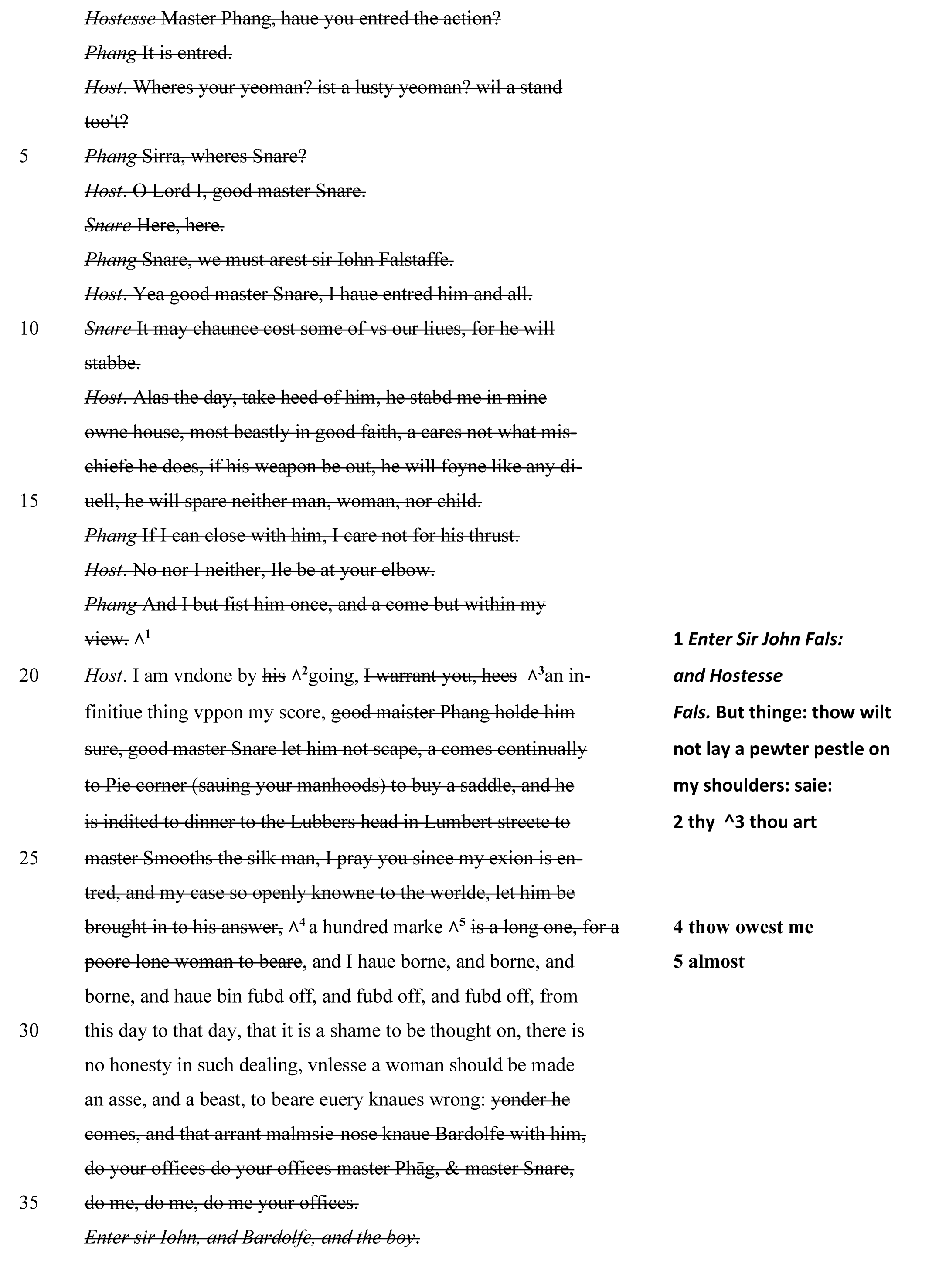

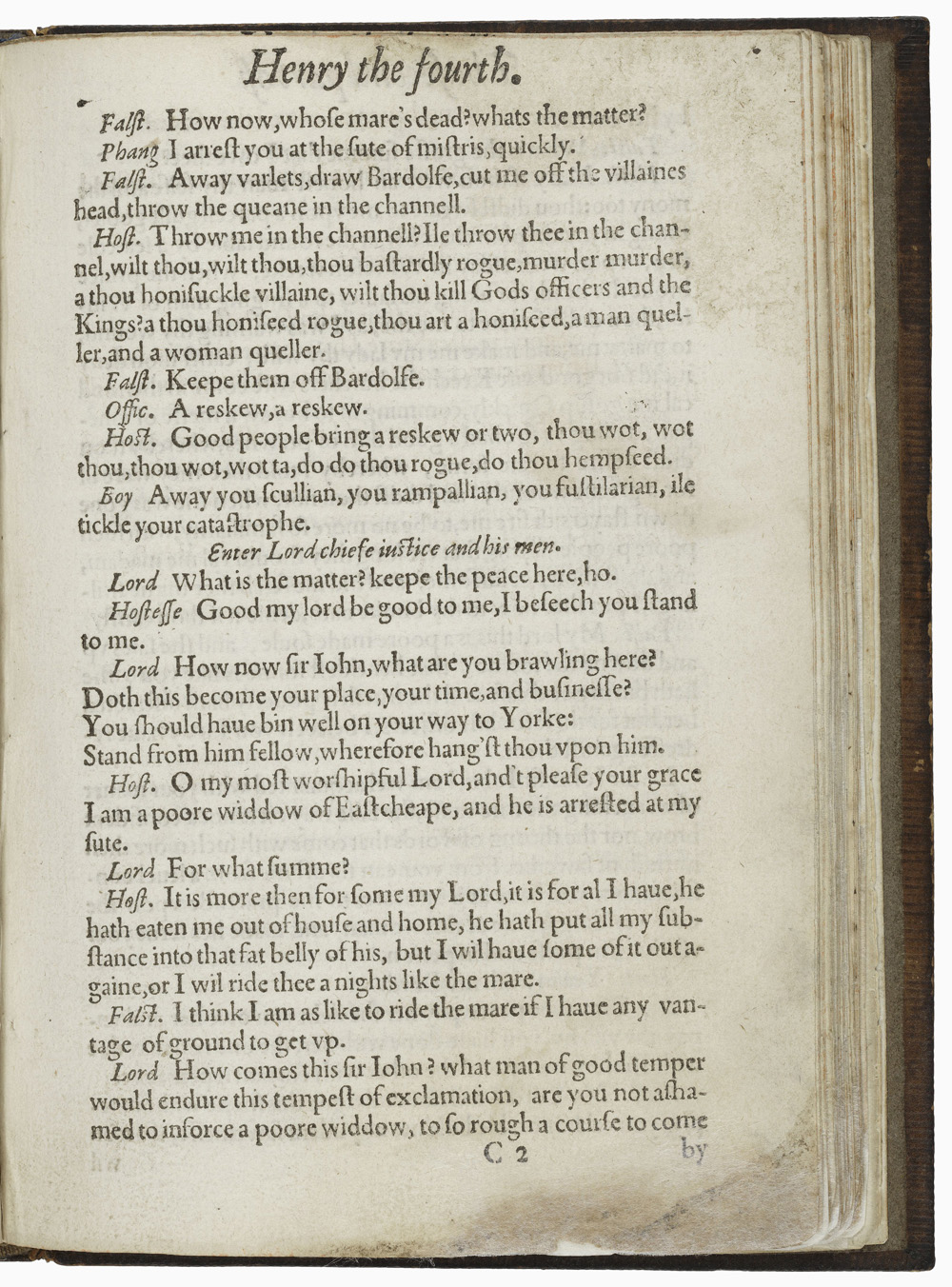

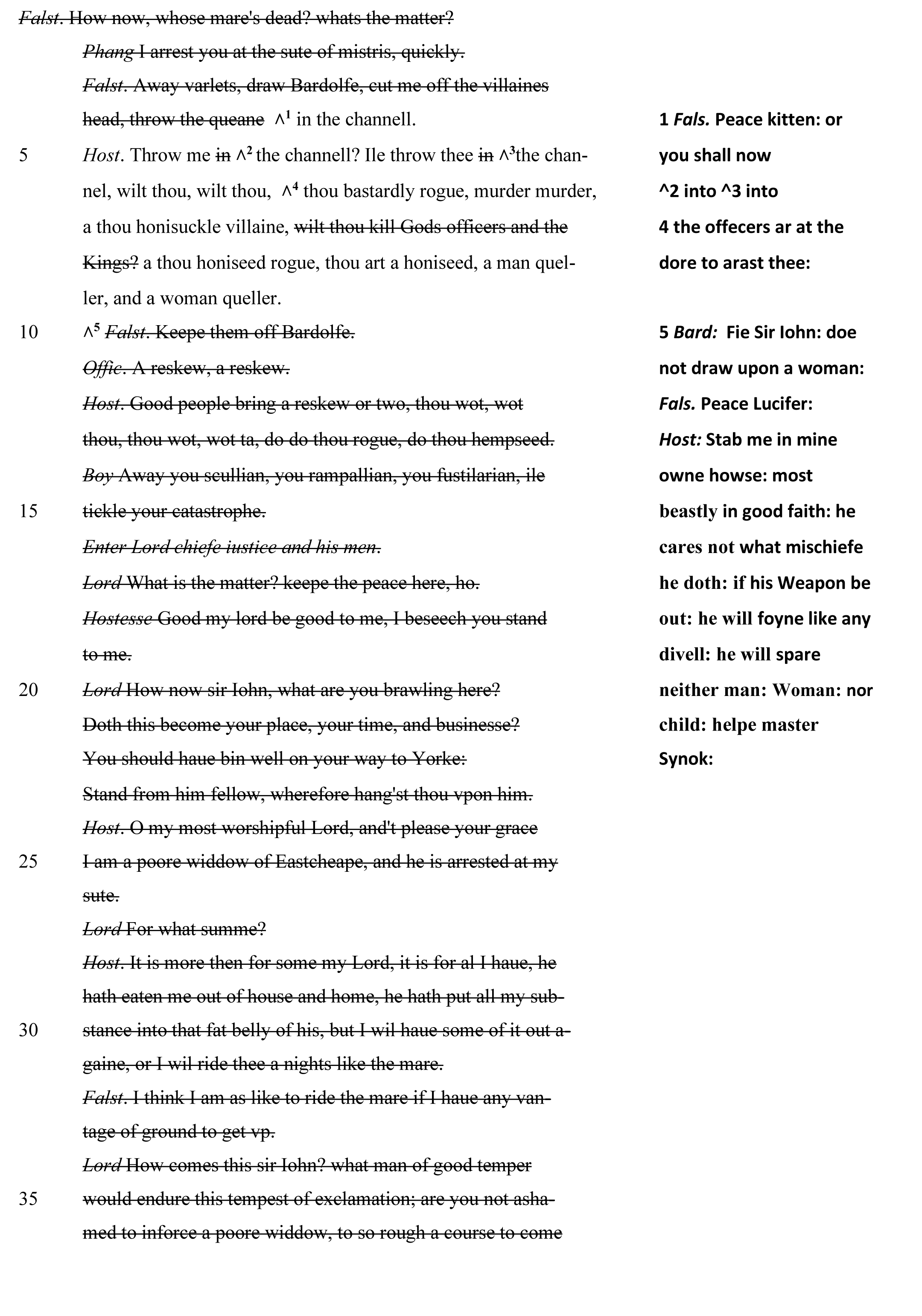

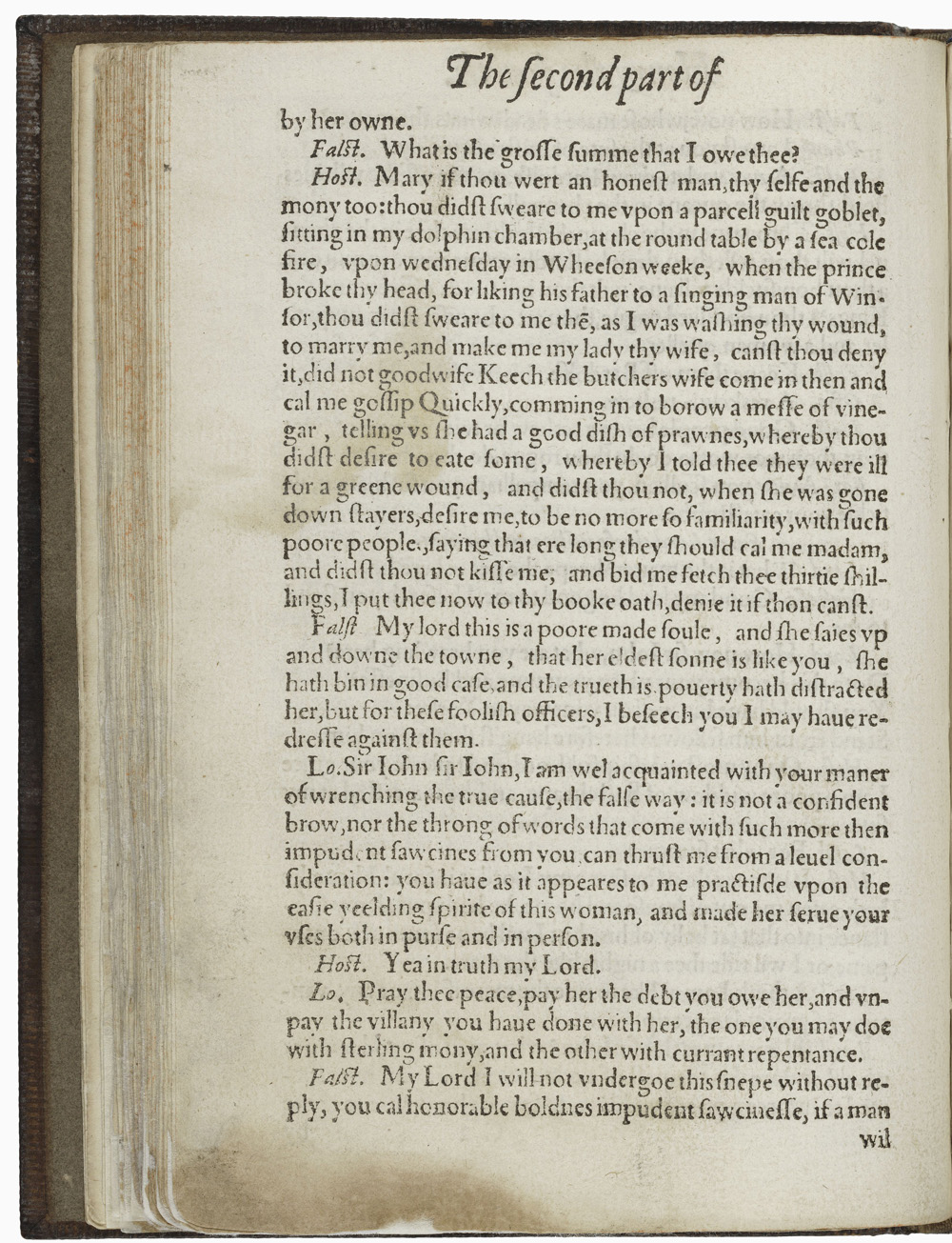

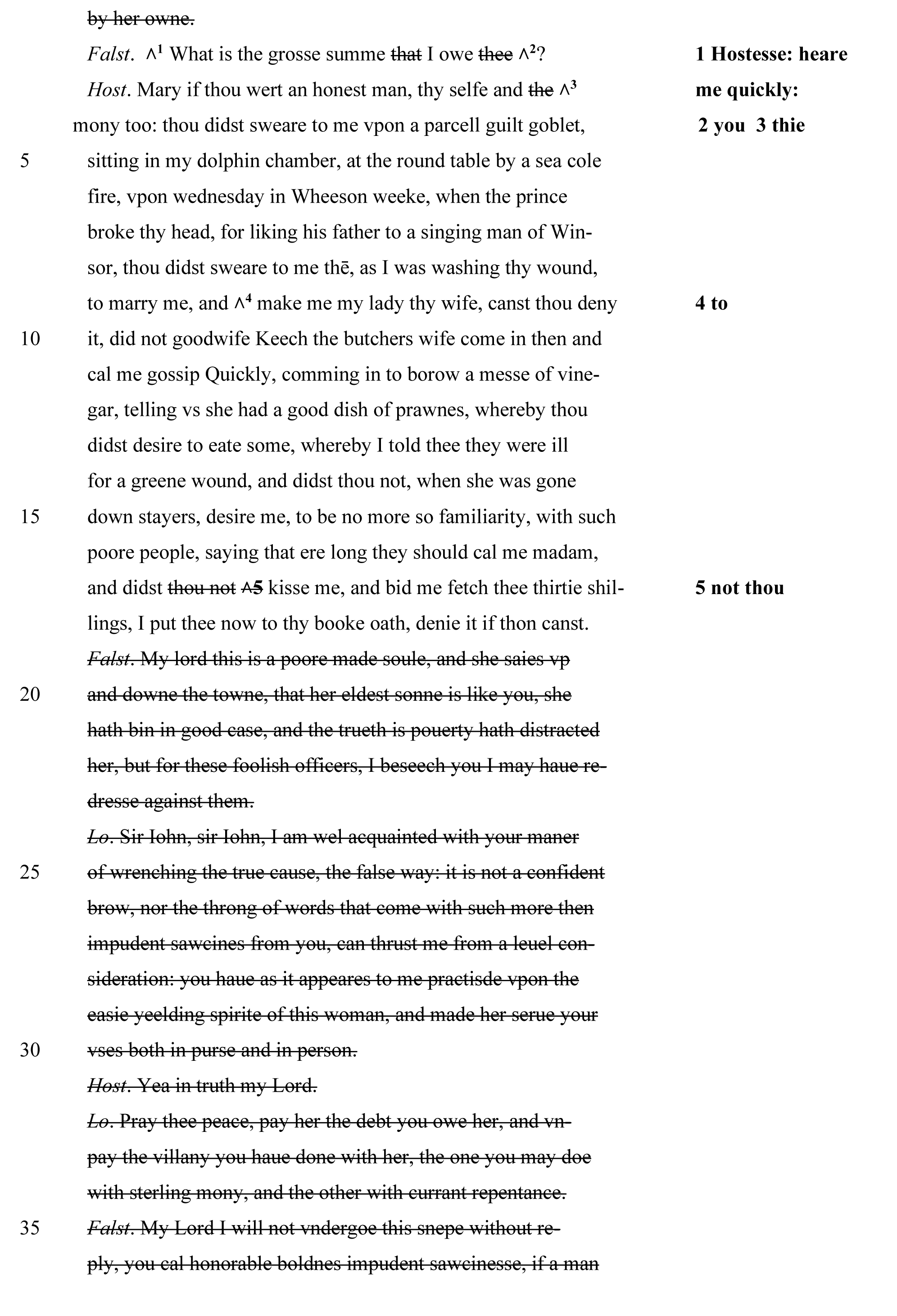

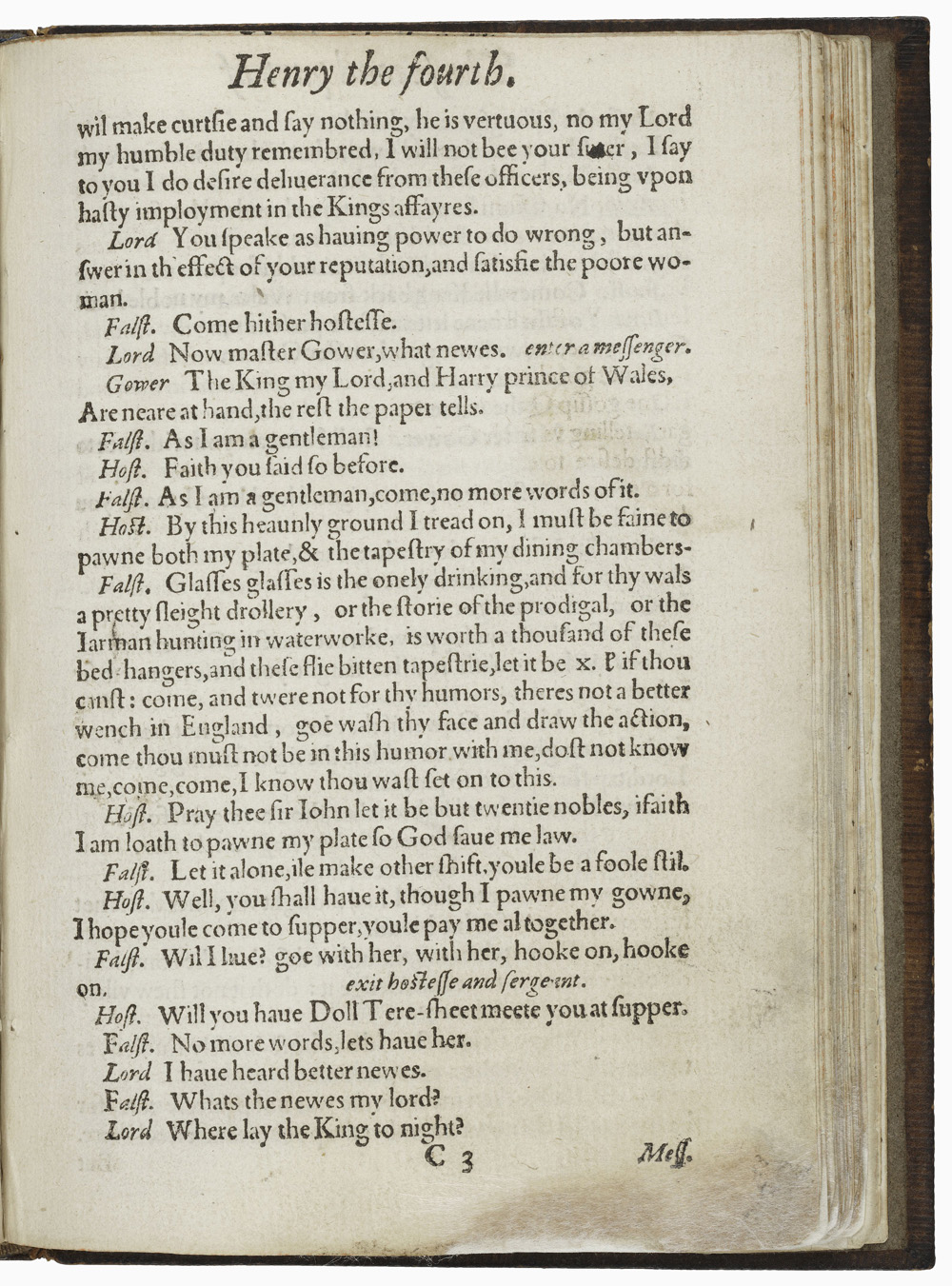

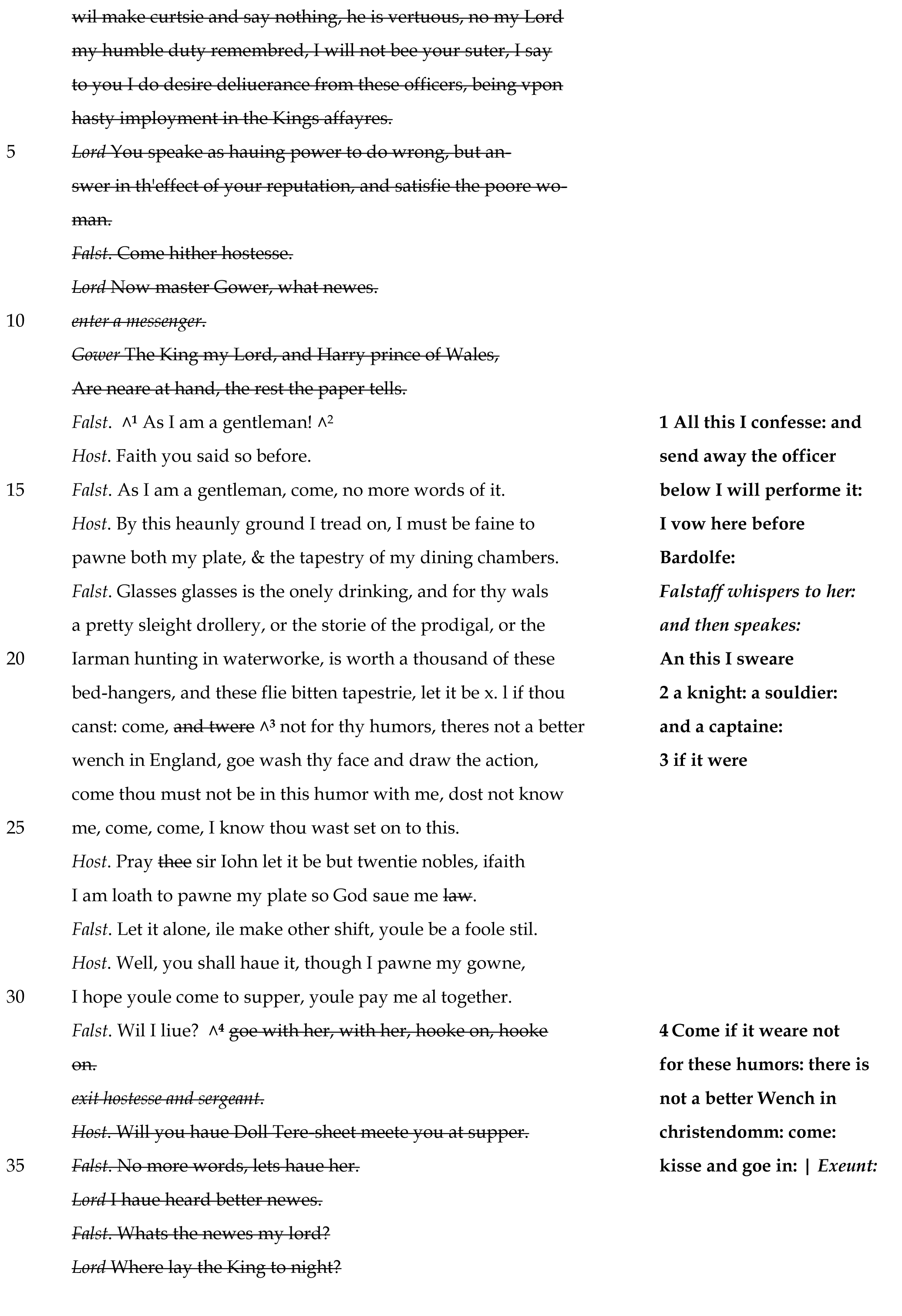

This section examines how Dering might have proceeded in marking up the two printed playbooks. The actual copies of the quartos that Dering used do not survive, so the following illustration is of necessity a reconstruction. What you will see is a letter-for-letter transcript of pages from surviving copies of the playbook editions onto which Dering’s conjectured annotations have been imposed.

A different font is used to represent Dering’s handwritten annotations. These simply echo the text as Carington copied it into the manuscript. No allowance can possibly be made for changes that Carington may have made. These almost certainly include regularization of spelling and punctuation to his own preferences. Carington might also have introduced light editorial changes, and was not immune from committing errors.

It is also unknown exactly how Dering would have marked deletions, or have placed the words he added. Passages of more than a few lines could if necessary be written out into a separate slip of paper of the kind we see in Dering’s addition to the opening speech. But new passages of any length are rare, and Dering could for the most part have utilized the limited space available to him between type-lines and in the margins of the printed page. For passages of more than a few words, Dering might have followed the common practice of writing up or down the margin after turning the book through ninety degrees, as he did when annotating the transcript on fol. 20r:

In the present reconstruction, no attempt is made to guess these details. A single strikethrough identifies deletions. All annotations are set in the right-hand margin. A standard convention is used of setting a large caret symbol ˄ at the point where added text needs to be inserted. Each caret is followed by a number. The number is repeated in the margin so that the insertion point and the note are clearly linked. To be clear: these are editorial conventions rather than an attempt to reproduce the annotated document in its detail. The restricted aim is to suggest the substance of the changes Dering introduced.

Overview

In 2 Henry IV Sc. 5 (2.1), Shakespeare begins to move the Falstaff plot forward, bringing the Hostess of the tavern on stage for the first time in the sequel play. Her relationship with him, presented here in more vivid terms than anywhere else, is touched with both sentiment and comedy. Yet it is starkly unequal for reasons connected with gender, social status, wealth, and, not least, linguistic competence. It shows Falstaff in a harsh light as sexual and emotional exploiter of the Hostess. She is attempting to use the law as a means to recoup money Falstaff owes her. Her efforts are given immediacy in theatrical terms through the presence of the aptly named Fang and Snare, officers seeking to arrest Falstaff. He evades arrest, first starting a fray to escape from the clutches of the law, then, when the Lord Chief Justice arrives with his men, conning the Hostess by reviving her hopes that he will marry her. The episode paves the way towards the long tavern scene, with its Saturnalian echoes of the post-Gadshill tavern scene in 1 Henry IV.

From Dering’s point of view, Sc. 5 (2.1) is typical of the comic matter of 2 Henry IV that he had decided to prune back severely. In the play as a whole the Falstaff of 2 Henry IV almost disappears. Dering cut Falstaff’s earlier confrontation with the Lord Chief Justice, the tavern scene, and Falstaff’s travels to Gloucestershire as well. But he is needed at the end of the play, so that Hal can make the decisive political gesture of rejecting him when he seeks favour with him as newly crowned king.

Dering therefore decided to keep one scene that would keep Falstaff in view in between his phoney triumph in supposedly killing Hotspur at the Battle of Shrewsbury at the end of Shakespeare’s 1 Henry IV and Hal’s rejection of him at the end of the sequel. He settled on a scene that was manageable in length, susceptible to cutting, and without any consequence for the plot that would demand further scenes to be preserved.

However, the scene he chose contained a good number of roles that would appear nowhere else in his adaptation, including Snare, Fang, Bardolph’s boy, and the Lord Chief Justice. The main task Dering set himself was to remove these characters, and therefore to eliminate the dialogue and action associated with them. The major cuts to the scene are all directed to this end.

In More Detail

On sig. C2r Dering retrieved some lines spoken by the Hostess that were part of the longer passage he had cut.

He also made some additions, which, though modest enough, are his most distinctive original contribution to the Falstaff scenes. He modified Falstaff’s threat to throw the Hostess into the channel (the city’s open sewer) by commanding her “Peace kitten”. The word “kitten” might sound affectionate, but in context is a less appealing diminutive than it might appear, as it reinforces Falstaff’s threat by suggesting the drowning of an unwanted cat.

In between the Hostess’s two speeches, Dering added the exchange between Bardolf and Falstaff in which Bardolf protests at Falstaff’s violence towards the Hostess: “Fie Sir Iohn: doe not draw upon a woman”.

At the end of her speech otherwise reproduced from the original Dering adds “helpe master Synok”. “Synok” is a name found nowhere else in either Shakespeare’s plays or Dering’s adaptation. It is presumably an error for, or alteration of, either “Fang” or “Snare”, though the process of alteration is unclear and puzzling.

Dering is poised between two strategies of adaptation. His overall aim was not only to cut the scene heavily, but also, as part of that process, to eliminate roles such as the two beadles and Bardolf. However, in the course of some unusually complex and detailed alterations he became caught up in a more expansive approach to the task. Two roles that are not otherwise required in the adaptation make a brief appearance in the adapted text.

The resulting inconsistency would need resolving in performance, and this could be achieved quite straightforwardly by deleting Bardolf’s exchange with Falstaff and the Hostess’s appeal to “Synok”. But Dering was clearly aware that his cuts risked taming the violence and offensiveness of Falstaff’s rowdiness too far, and was anxious to offset this effect.

Dering’s uncertainty in this passage may also be related to his reworking of the immediately preceding leaves, which was so extensive that he had an entire section recopied.

PREVIOUS: Take a deep dive into the drafting and revision of the text of the Dering Manuscript.

NEXT: Read about Dering’s review of Carington’s transcript.