1.3 The Manuscript as Document

Opening the Box

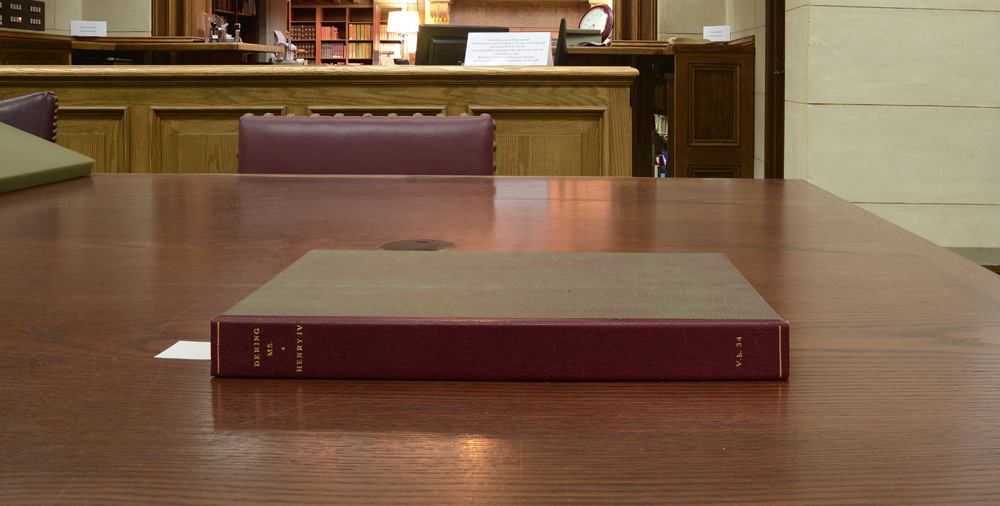

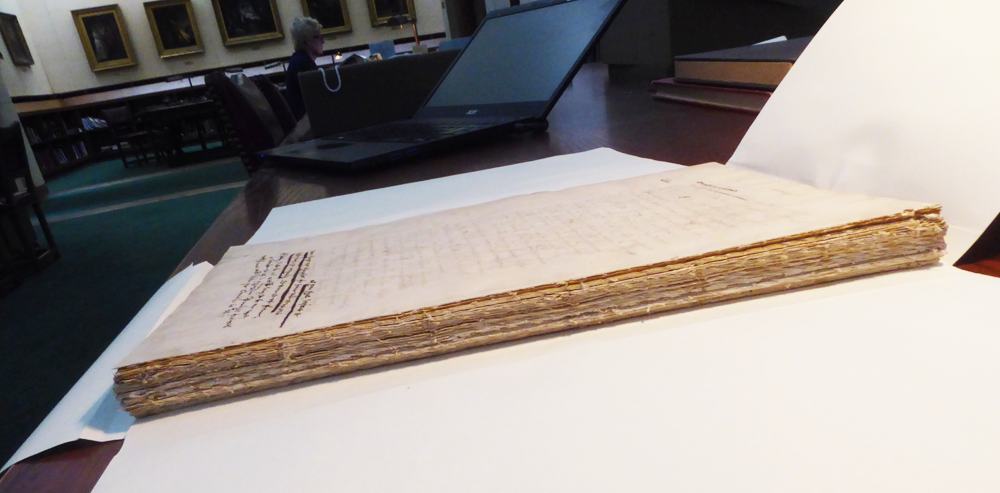

The manuscript of Henry IV is now in the Folger Shakespeare Library, where it is currently kept in a clamshell box. It consists of fifty-five folio leaves. The spine reads “DERING | MS | [large dot] | HENRY IV” at the top, and has the Folger shelf mark “V.b. 34” at the bottom.

When the box is opened, the manuscript lies inside, covered by a fold-out made of heavy paper leaves from a single cut sheet.

Overall Description

The manuscript of Henry IV consists of fifty-five folio leaves into which the play is written, measuring 11.75 x 7.75 inches, numbered in modern pencil in the top right-hand corner. At a later date, a separate two-sided slip of paper has been inserted in a blank original leaf (referred to as fol. *) at the beginning of the manuscript. The insert contains a list of performers and roles for an entirely different play, John Fletcher and Philip Massinger’s The Spanish Curate, which Dering was evidently planning to perform before he turned to Henry IV. This is described in a separate section as evidence of Dering’s cast as he might have envisaged it for Henry IV also.

J.O. Halliwell’s original description of the manuscript in 1845 refers to three flyleaves, blank except that one of them was marked “A 5”. These leaves were presumably removed when the manuscript was subsequently bound.

The Paper

One of the regular outgoings listed in Dering’s Book of Expenses is for the purchase of paper, which he used in large quantities for record-keeping and in pursuit of projects such as his investigations into heraldry. The paper varied greatly in quality and volume, and at the cheaper end was not expensive for a purchaser of Dering’s means. On 2 January 1623 he spent one penny on an unspecified but small quantity of “paper”; on 1 December two shillings afforded him “6 quire of paper” at 4d per quire. In contrast in terms of cost, on 11 March he purchased “A Reame of royall paper” for £1 3s 6d. Much of this expensive ream of the finest paper (20 quires) was earmarked for Dering’s study of heraldry. Dering’s pursuit of heraldic prestige made March a particularly expensive month in terms of paper-buying. On 16 March he invested 10s in “A print Cutt in wood for to print blanke Escocheons in paper royall,” and on 27 March paid a further 8s 6d for “printing of 14 quire of royall paper viz: printed with blanke escocheons.” The paper for Henry IV was of a more ordinary kind, either taken from cheaper unfolded sheets, or ready folded and sewn in book form, as with the “4 paper bookes” purchased for 14s 10d on 11 April 1621. As the various sections of the manuscript share the same stitching holes, it would seem that they were more probably unstitched until the manuscript’s leaves were finally sewn together to make a unit.

Dering’s use of the term “quire” refers to the stack of leaves as purchased. This would usually consist of 24 sheets, a unit that would have been insufficient for the transcript of Henry IV. The term can also apply to any number of sheets as folded together into a single gathering. This will be the usual sense in the discussion that follows. The manuscript of Henry IV is a folio, meaning that the sheets have been folded once to make two leaves. The document as a whole is made up of more than one gathering, or quire, and the number of sheets that make up a gathering varies between one quire and another.

The leaves are now mostly separate, but six of them, fols. 15-22, are still are conjugate pairs made up of three sheets folded together, “conjugate” meaning that the two leaves are demonstrably two halves of the same sheet, in that the folded sheet is still intact as a single entity.

Elsewhere, the leaves are now no longer found in conjugate pairs, the fold at which they were joined having been trimmed or worn away. The manuscript needs further examination in order to establish its original structure. That examination not only reveals its structure; it also shows that a number of leaves from the original quires were later removed, and replaced with six leaves from another stock of paper, inserted in between the two original quires.

Six Added Leaves

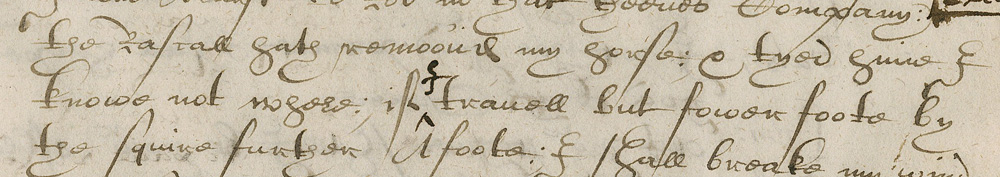

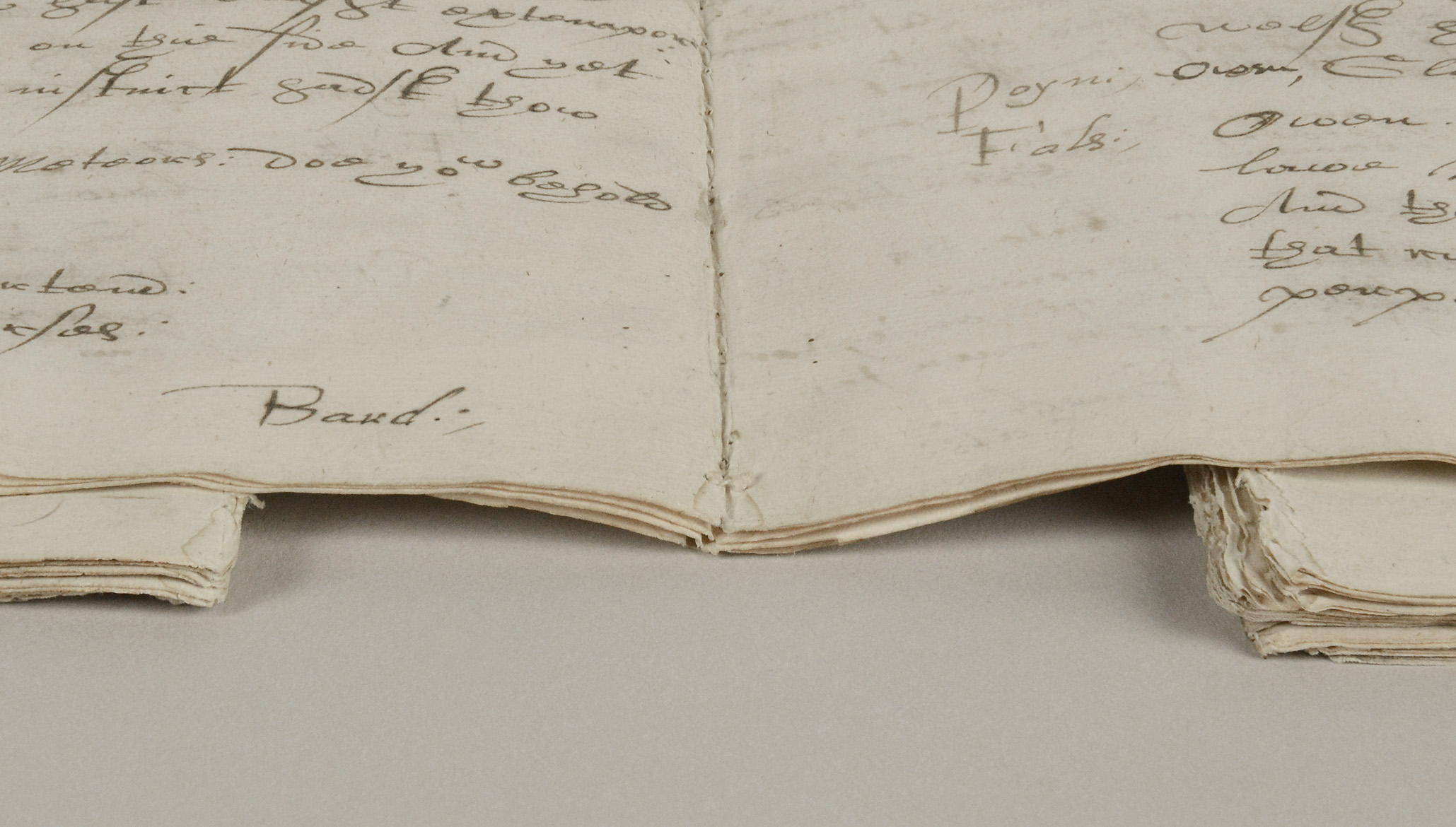

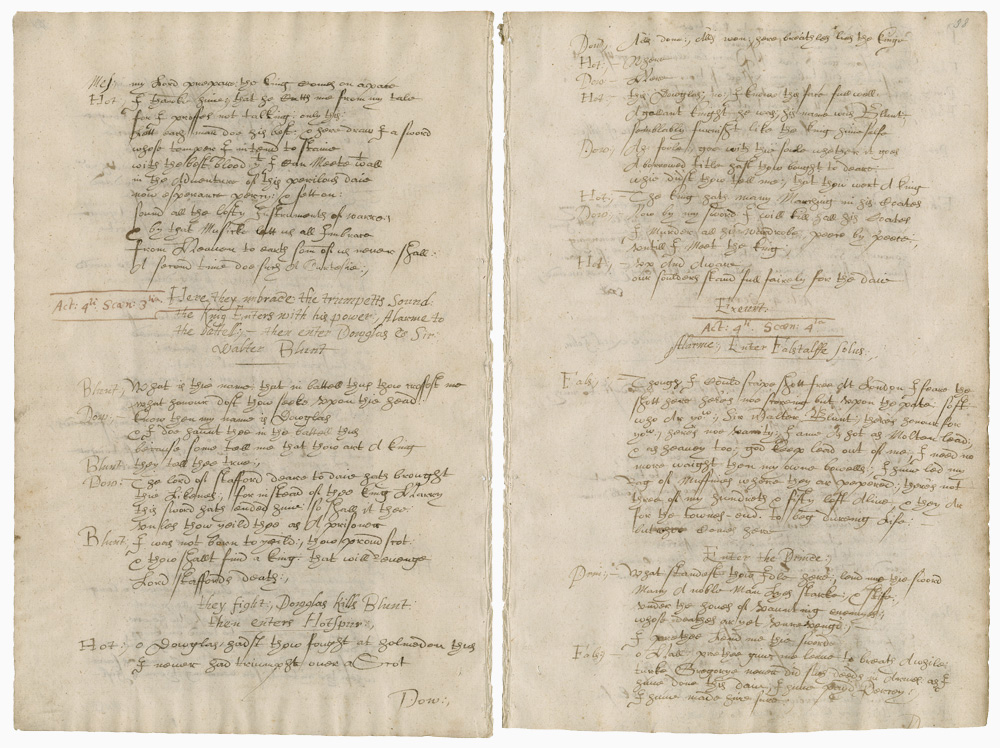

The illustration shows two consecutive pages in the manuscript that belong to these different stages in its construction. To the left is the verso of a leaf, fol. 37; this is part of Carington’s first transcription of the entire play. To the right is the recto of the first of a separate sequence of six leaves, fols. 38-43, again inscribed by Carington; this sequence replaces leaves of the original transcript that are now lost. It can be seen at a glance that the written area of the right-hand page is longer than that of the left-hand page.

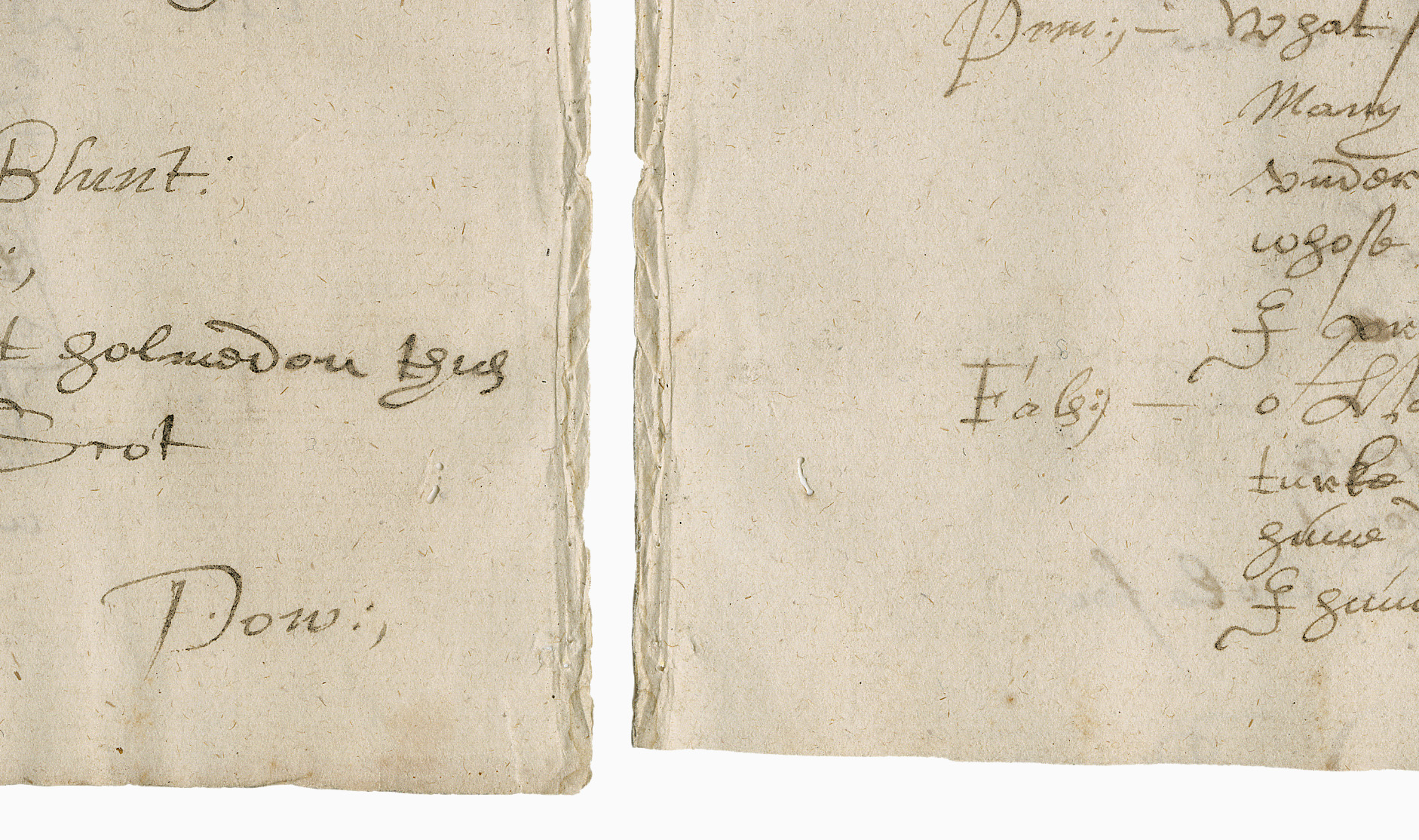

A closer look at the foot of these pages makes it clear that two different stocks of paper were used. The bottom edges of the six leaves are more irregularly trimmed, and are slightly shorter than those of the rest of the manuscript.

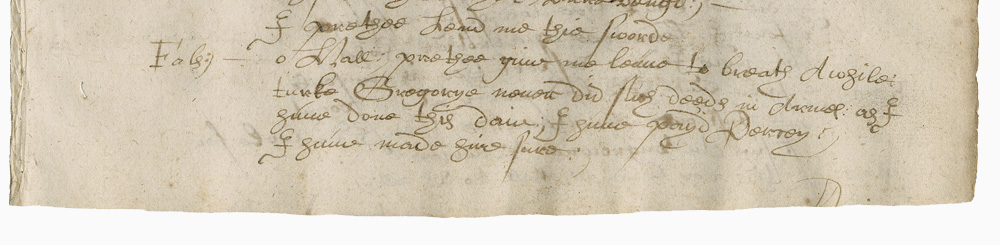

Originally, however, they would have been significantly longer than they are now. The trimming was demonstrably done after inscription, as is demonstrated by the fact that on two consecutive pages, the one illustrated here on fol. 38r and its recto (fol. 38v), the catchword at the bottom of the page is partly cut off:

Another catchword on fol. 39r may have been removed in its entirety. None of the catchwords in the original transcript has been cut in this way, and indeed it is probable that the original leaves were cut to their present size before inscription happened. On fol. 21v, for instance, the catchword is placed on the same line as the “Exeunt”, suggesting that the page already lacked any further space below this line when the catchword was written.

As Laetitia Yeandle first demonstrated, the separate trimming of the six leaves demonstrates that these leaves represent a different and later stage in the development of the manuscript from the leaves coming before and after.

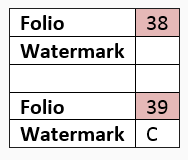

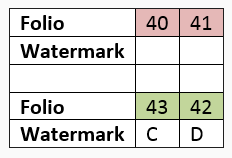

However, the six leaves are not themselves homogenous. Their bottom edges are trimmed separately in pairs as follows:

fols. 38 and 39

fols. 40 and 43

fols. 41 and 42

This indicates that the leaves, though now separate, were originally conjugate in these pairings. So the six leaves begin with a single folded sheet of two leaves (fols. 38 and 39), which is followed by two sheets folded together to make a quire of four leaves (fols. 40 and 43, fols. 41 and 42).

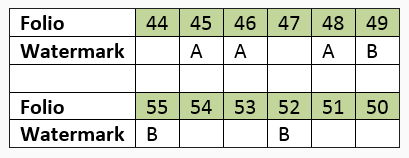

Watermarks

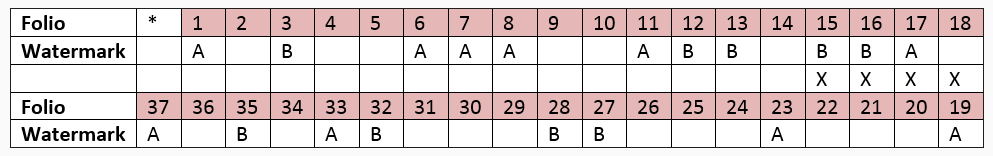

The watermarks confirm that this is how the six leaves were assembled. Indeed, an examination of the overall sequence of watermarks in the manuscript reveals exactly how it is constructed as a whole. It demonstrates decisively that the six leaves are from a completely different stock of paper from the rest of the manuscript. And it demonstrates how the leaves of the whole manuscript were folded into quires.

The watermarks, as they will be identified in the following analysis, are as follows:

A, B: a pair of similar watermarks in the form of a single-handled pot with crescent top, incorporating the initials “PO” in mirror image across the pot belly and “I” in the stand. It appears to be a variant design of Gravell POT.181.1, as illustrated here. In A the initials are the right way round when the watermark is viewed from the felt side of the paper (i.e. the side that was facing up when the paper was manufactured on the horizontal frame into which the watermark image was made in twisted wire); in B they are seen in mirror image when viewed from the same side.

C: two mirror-imaged watermarks incorporating two pillars and letters perhaps reading “A R0”.

D: a single-handled pot incorporating the letters “I/AV” with quatrefoil top, similar to Gravell POT.004.1 and POT.004.2. The chainlines are wider than in leaves with watermarks A and B.

The Structure of the Manuscript

The structural makeup of the manuscript as revealed by the remaining conjugate leaves and the watermarks is shown in the following table. Vertical columns in the table show conjugate leaves; for example leaf 1 is conjugate with leaf 36. The middle of each folded quire is at the right-hand end of each row. The leaves of the second half of the quire arranged in reverse order to maintain the conjugate pairing of leaves. The leaves that are still conjugate in the manuscript as it now survives (leaves 15-22) are marked ‘X’. These make up the middle of the first quire. The leaves containing Shakespeare’s 1 Henry IV are shaded pink; those containing 2 Henry IV are shaded green.

The strength of the evidence of watermarks depends on the irregularity of the sequence in which they appear. Once folded in two, each sheet has a watermark in the middle of one of its leaves. Therefore conjugate leaves must always have a watermark in the middle of one leaf but not the other. But the watermarks do not neatly occur on alternate leaves. In the two long quires it is therefore difficult if not impossible to arrange the leaves in any sequence other than the one shown in the table. In other words, the two long quires must always have been separate, and neither is divisible into smaller quires.

This account of the paper has been purely descriptive, making no more than incidental reference to the words written into the document. It has been intimated, however, that the structure of the manuscript reflects two separate stages of inscription.

Sewing and Binding

The quires of the manuscript might in principle have been either sewn as separate units before inscription or joined together after inscription (or both). The present examination has not revealed any stitching holes that might result from separate sewing of quires.

The picture is complicated by stitching holes that were made when the manuscript was bound in the nineteenth century. Altogether, three sets of holes can be identified:

(a) Larger holes in the gutter (i.e. the paper adjoining the fold and available for stitching) that are now usually trimmed away in whole or part. They occur at 10mm, 50mm, 97mm, 145mm, 193mm, 242mm and 285mm from the top of the page (fol. 44 measured). They appear as darker shadows running through the whole manuscript when it is viewed from the side.

(b) Larger holes at 12mm and 122mm from the top of the leaf, up to 9mm in from the present gutter edge (fol. 44 measured), furthest from the gutter in the outer leaves of the large quire, not visible in some inner leaves, clearly visible in the inserted leaves.

(c) Small regular holes close to the gutter edge, about 8mm apart. These are probably for the nineteenth-century binding.

We can be most confident that the first of these sets originated with the seventeenth-century sewing of the manuscript, because the later trimming of the gutter deprived them of any functionality. The vestigial presence of these holes throughout the manuscript shows that it was sewn after the additional quires had been inserted, and so after the manuscript was fully copied out.

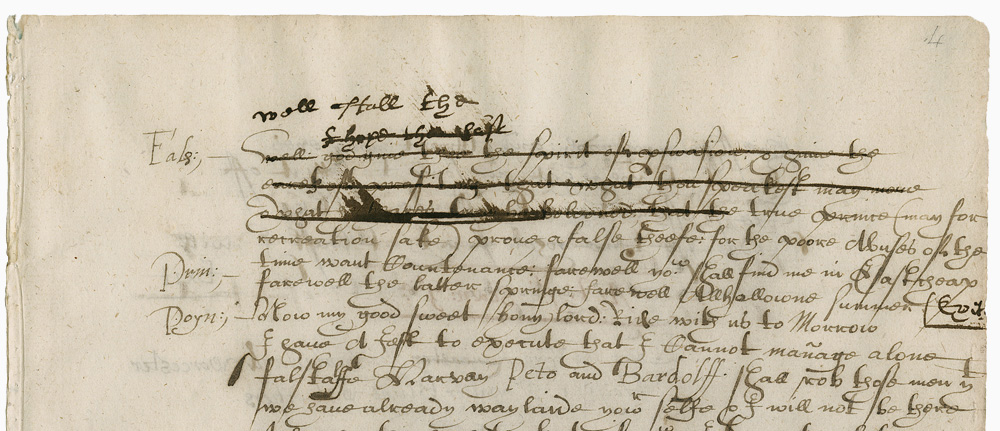

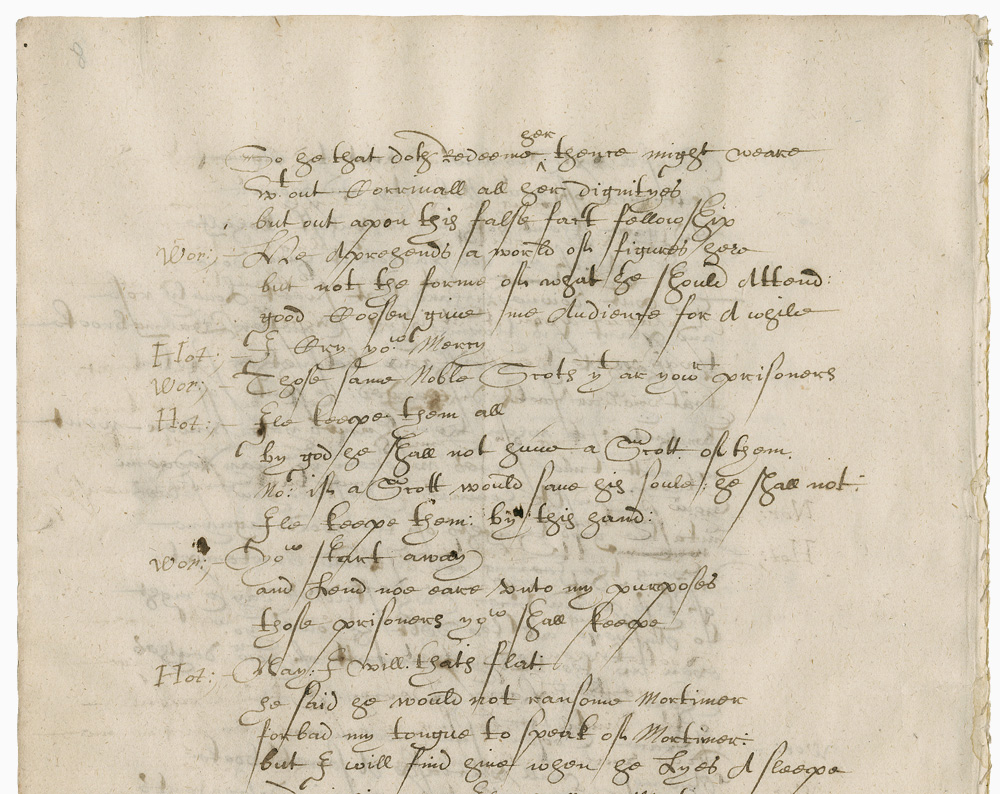

The Hands

As the Book of Expenses indicates, the manuscript is mainly in the hand of a scribe identified as Carington; the second hand is that of Dering himself. Despite Carington’s contribution by way of copying out almost the entire play, it is nevertheless appropriate to emphasize Dering’s personal agency in the overall process of putting together the adaptation. He acquired the printed books, and it was he who probably modified them to supply Carington with his copy. Before he handed over to Carington, he himself copied out the first recto of the text. After he had finished his task, Dering made further modifications.

The reason why Dering copied out the first page is doubtless that he was instructing Carington in the layout of the text by providing him with a model to imitate. He reverted from the indented speech-prefixes of his quarto copy to the marginal speech prefixes typical of a playhouse manuscript, establishing a straight left-hand margin presumably with a light fold. This separation of textual elements into columns is consistent with his practice elsewhere in documents such as his commonplace book, his accounts, and his library catalogue. For example, in the commonplace book the authors are listed in a narrower left-hand column opposite the wider right-hand column in which the quotations are written. Dering would have been capable of applying the same logic to speakers and their speeches. Nevertheless, given his “slightly obsessive” interest in the London theatre1 and his retracing of its professional practices in his preparation of a scenario for a play called Philander, King of Thrace,2 it would not be remarkable if Dering was familiar with the appearance of a theatre manuscript. Indeed, he had evidently acquired a manuscript of The Spanish Curate not long before compiling his adaptation of Henry IV (see Household Performance).

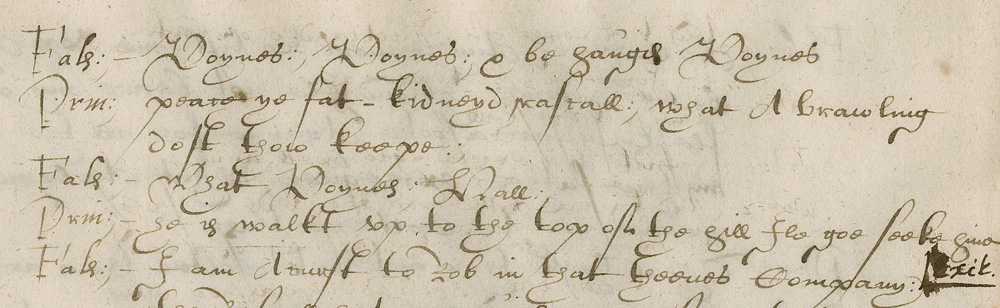

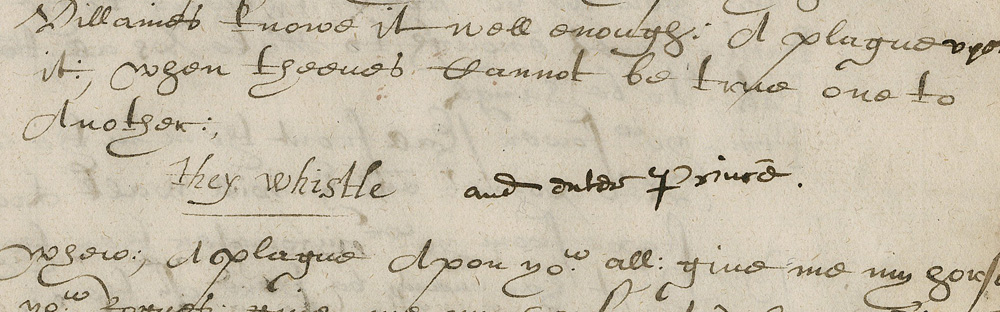

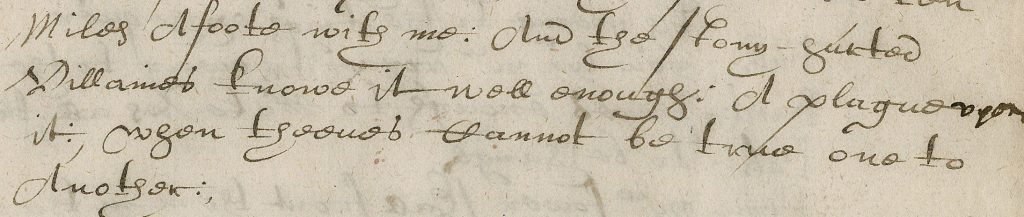

Carington followed Dering’s separation of speech prefixes. There are no indications that he did anything more than execute the function of a scribe in copying. But to copy is nevertheless to impose a style of presentation. Carington’s script is in a regular and legible secretary hand for dialogue, with italic for stage directions and the marginal speech prefixes. To an even greater extent than is usual in late Jacobean scribal practice, the most common punctuation mark is the colon, which functions as an equivalent to various modern forms of punctuation, including the full-stop at the end of a speech. In this respect he differed from Dering, who actually reduced the number of colons in his copy.

With only one exception (“Exit”, fol. 4v), Carington’s stage directions, including exits, are placed on separate lines and are centred.

Speech prefixes are for the most part elaborately separated from the dialogue by a colon followed by a curved stroke like an elongated comma and a short dash. It might appear from the slight but persistent misalignments that the speech prefixes were added after the dialogue, but at one point there is textual evidence that makes it unlikely at that point at least.

After Carington handed over his transcript, Dering annotated it, using a heavier and blacker ink, and writing in a less even and more angular style. As will be seen, the materially separate section from a different stock of paper is the outcome of Carington copying that part of the play twice. This section was annotated by Dering after the second transcription.

In marking up the transcript as a whole, Dering paid particular attention to the practical challenges of performing his adaptation. He introduced further cuts, and made other adjustments, including transpositions, alterations of dialogue to take account of cuts and simplifications of staging, a few purely literary adjustments, and corrections of Carington’s mistakes.

Dering also added act and scene divisions in a reddish ink, and so established the dramatic structure of his new work.

Stages of Preparation

1. Dering prepared a cast list for his envisaged production of The Spanish Curate.

2. He marked up his copies of the quarto of 1 Henry IV and 2 Henry IV with alterations, mainly cuts, and assembled quires of folded paper for his adaptation.

3. On the first written leaf he wrote the title as ‘ he istory ff ing enry he ourth.’, thus omitting the initial letters “T,” “H,” “O,” “K,”, “H’” “T,” and “F,” in italic script. He presumably intended to add the initial letters in red ink (see stage 7), but failed to do so. (Therefore the standard form of the title as given today depends on seven emendations.) Below this title, he copied out the opening stage direction, in italic, with generous spacing on either side and spacing between lines, thus allowing for later annotation. There follow the first speech prefix ‘King’, in italic, and King Henry’s opening speech of twenty-eight lines.

4. Carington took over and transcribed the rest of the play in its entirety, leaving extra space between lines for most but not all scene breaks.

5. Dering modified the transcript with alterations in heavy black ink.

6. The alterations to the beginning of 2 Henry IV were so excessive that Carington prepared a fresh transcript of six leaves to replace it, along with the end of 1 Henry IV.

7. Dering made further annotations to the second transcript, and added act and scene divisions in redish ink across the whole manuscript.

8. At the end of the play he wrote five and a half lines over Carington’s last three lines, which were written in a lighter script.

9. Perhaps at this late stage, he used the reverse side of the Spanish Curate slip to write an additional eight lines for insertion into King Henry IV’s opening speech in the page he had originally copied.

PREVIOUS: Learn about the Henry IV manuscript that Dering owned and annotated.

NEXT: Read about the manuscript’s journey from Surrenden, Kent, to the Folger Shakespeare Library.